Blacksmith Yoshihiro Yauji pulls a piece of glowing metal from the forge in a Japanese village, continuing a tradition dating back centuries to when the region was renowned for crafting swords carried by samurai.

He places the steel under a spring hammer and the sound of the metal being flattened and fortified into a kitchen knife echoes off the mountains surrounding the workshop.

“I believe that blades are the foundational root of Japanese culture,” 40-year-old Yauji said. “If you can condense 700 years, 1,000 years or 1,500 years of technology into a single product, the appeal of the product will be different,” he said, adding that at first, he wanted to make “katana” swords once wielded by samurai.

Photo: AFP

Yauji started at 20 as an apprentice to Hideo Kitaoka, who helped found the collection of cooperative workshops that make up the Takefu Knife Village. After 18 years, Yauji launched his knife line in 2021. But in the 1970s and 80s, the city of Echizen where the knife village is located was in crisis, with artisans unable to compete with cheaper mass-produced tools. Kitaoka and other top blacksmiths banded together to form a cooperative association and, with the help of famed designer Kazuo Kawasaki, began producing designs that turned Echizen knives into works of art.

“At the time of my boss’s generation, the environment was not like it is today; they were struggling just to survive,” Yauji said. “My generation is on the upswing. So I feel it is necessary to once again improve our skills for the brand and its value to continue to exist.”

Around 80 percent of Echizen-made knives are now exported, Yauji said, making their way into professional kitchens around the world and even featuring on hit TV series The Bear.

Photo: AFP

HAND FITS THE KNIFE

The forge at Takefu burns at 900 degrees Celsius, and the handmade Japanese blades drawn from the molten orange core, once hammered, shaped and polished, are sharp enough to split a hair.

“The Japanese knife brings out the best of ingredients. Texture, bitterness, sweetness,” Yauji said. “I think it is a knife specialized to bring out the true flavor of the ingredient itself.”

Knife makers can spend an entire day perfecting a single piece. The metal is heated until malleable and then hammered — a process repeated several times — before being shaped, quenched in oil or water and left to cool. Once the temperature is stable, it is ready to be sharpened. Most blacksmiths hand the knife over to dedicated sharpeners at this stage.

Then, the utensil is ready for the final step of the process: handle making.

“Japanese cutlery is, in my opinion, about the hands learning to fit the tool” instead of the knife being designed for the comfort of the user, Yauji said. “It is a way of trying to establish a deeper connection.”

‘SOUL OF A CHEF’

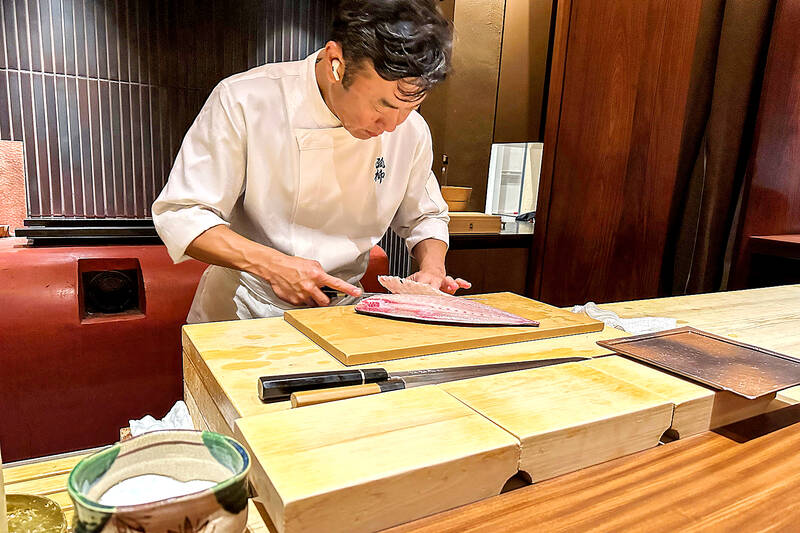

Using his custom-made yanagiba (willow-leaf blade) sashimi knife, Chef Shintaro Matsuo slices a buttery slab of fatty tuna at acclaimed Osaka restaurant Koryu, considered one of the best fine-dining establishments in a city dubbed Japan’s kitchen.

Matsuo’s dishes combine subtle flavors using ingredients from the surrounding Kansai region, all artfully presented with the help of blades made in Sakai, a small town on the outskirts of Osaka that is considered Japan’s hocho (kitchen knife) heartland.

“The knife is an extension of my hand,” the chef explained, proudly wielding the elongated blade specially made by blacksmith Minamoto Izumimasa.

“Japanese steel allows the flavours of the food to remain intact,” Matsuo added.

Chefs in the country spend years honing their knife skills and patiently learning to master blades that are often more challenging to use and require greater expertise.

“Japanese people have a unique sense of beauty when it comes to cutlery,” said Ryoyo Yamawaki, whose Sakai-based company has been making knives since 1929. “Since ancient times, the Japanese sword is said to have been the soul of a samurai, and the knife the soul of a chef.”

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand