The Sino-French War often appears to be a speed bump in history, quickly bounced over on the way to the monumental changeover to Japanese rule in 1895. The occupation of Keelung left us with some interesting defense works and a trench system still crumbling away on the city’s ridges, but the French occupation of the port for seven months in 1884 and 1885 is largely remembered for the cemetery it left behind, a popular media historical topic.

The Treaties of Tianjian between the Manchu Empire and Russia, France, the UK and the US opened up the colonial holdings of the Manchus not only to western business interests, but also to foreign missionaries. Catholic and protestant missionaries soon moved into Taiwan.

George Mackay, the most famous of the Western missionaries working in Taiwan, arrived in 1871, his presence a result of the Treaty. The Wiki page on Mackay has a robust discussion of how Christian converts burned Chinese “idols.” However, there is nothing on that page or the Wiki page on the French occupation of Keelung of how the French invasion led to the burning and looting of Christian churches across northern Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Indeed, it is surprising how difficult it is to find detailed information in English on the repeated attacks on Christian churches that took place at various times in Taiwan after 1860. They seem to have dropped out of the collective memory, temporary blips on the march of progress, seldom referred to in popular media presentations.

ATTACKS ON CHRISTIANS/CATHOLICS

The redoubtable James Davidson in the classic Island of Formosa Past and Present (1903) identifies the pivotal year as 1868: “...a year which made it plain that either the foreigners must forsake Formosa once and for all,” or they must find some more successful way of dealing with Manchu officialdom than useless formal complaints.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Davidson argues that the campaigns against Westerners had been pre-arranged, since they emerged at both ends of Taiwan. Protestant missionaries had already been successfully evicted from Tainan, and the taotai (道臺), the island’s highest official, rejected a Roman Catholic land purchase in the city. Officials whipped up the population, and attacks on Christians and their churches in southern Taiwan began.

Nearby churches were sacked and destroyed, and local Christians attacked, one becoming the island’s first local Christian martyr. An account of the events cited by Davidson says that a Christian in Kaohsiung was murdered and “his body cut in pieces, and his heart eaten by some of the bolder of his murderers at the north gate of the old city.”

In May Roman Catholics in Tainan were attacked again and one of them was “bambooed” and imprisoned.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The attacks continued throughout the summer, in concert with confiscations of goods for export and, in August, imposition of absurd customs fees and a “mast tax,” the latter specifically forbidden by the Treaties. In July near Tainan, soldiers attacked and destroyed a church.

By September it was obvious to the British that something had to be done about the streams of broken promises and officially-sanctioned assaults on foreigners. These included, at one point, the taotai himself offering US$500 for the head of a foreigner who was traveling on the island using a consular passport, since the taotai would only issue permits to foreigners for travel to Kaohsiung and Tainan.

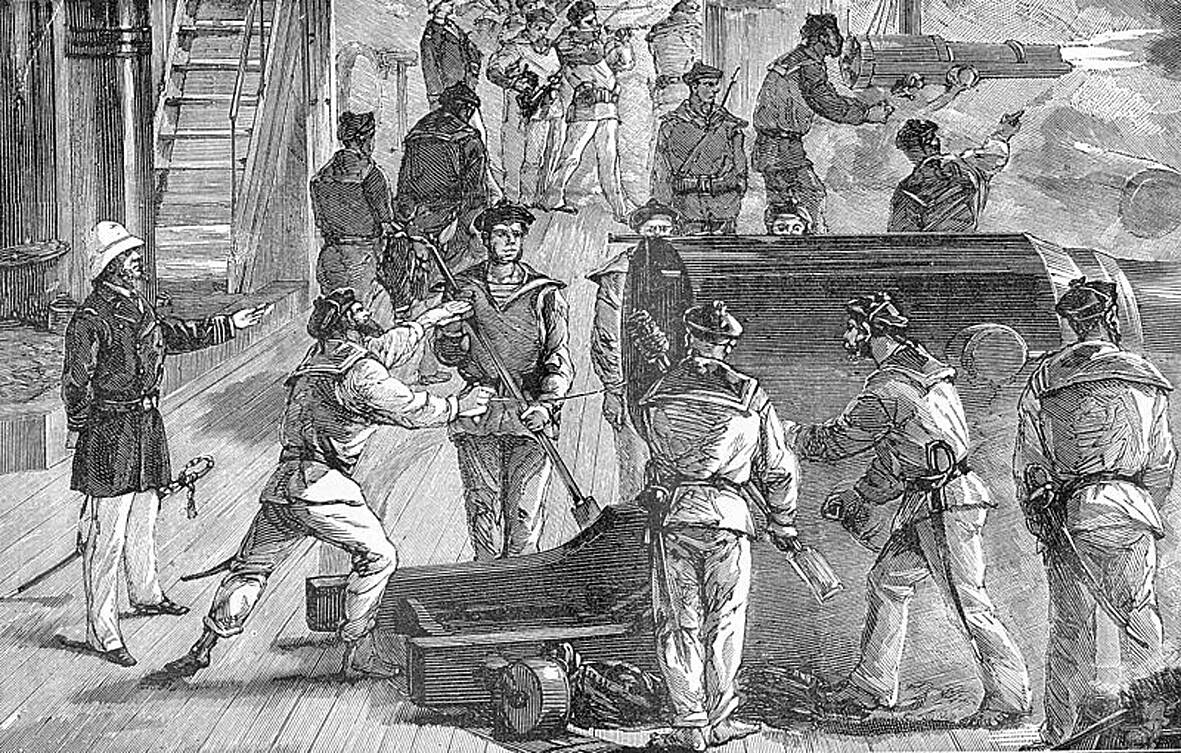

THE GUNBOAT AFFAIR

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Autumn passed and the problems continued, with no redress in sight. Finally in November the British Consul in Takao, John Gibson, decided to take two gunboats and occupy Anping, saying that the fort was the key to the island’s capital. A Lieutenant Gordon led the expedition. On Nov. 22, the fort was quickly occupied as it had been deserted by its defenders, but since it was in terrible condition, the British forces were withdrawn and one of Gordon’s two gunboats sent back to Amoy with the news.

Three days later, 500 local soldiers arrived and started to repair the fort and install cannons. Gordon and his superiors, alarmed at the prospect of facing such a force with his lone gunboat, demanded that the repairs cease immediately or he would open fire, which he did at 3pm that day. Gordon led an attack on the fortifications that night, and by the next day, the taotai in Tainan was promising to fulfill any demand he made.

The gunboat affair secured indemnities for a merchant whose property had been at the heart of the disputes with the taotai, and for the protestant church that had been destroyed. Foreigners received the right to travel anywhere on the island. The authorities issued edicts and proclamations affirming that the things said about Christians were nonsense, and missionaries obtained the right to work on the island. The taotai and other officials were removed.

Davidson credits Consular Gibson with creating a great change in the way foreigners were treated in Taiwan. The island, he averred, once considered a land of great danger, became safer. Problems would occasionally appear, “especially in the north,” but officials, instead of laughing at foreigners, would resolve them.

At the same time events in Tainan were playing themselves out, the Americans and British brought in gunboats to Tamsui to end the anti-foreigner campaign there. Davidson writes: “the year 1868 may be said to have ended in a very satisfactory settlement of disputes long standing in the north and south.”

Though there were attacks on Christians in the late 1870s in the north, by and large things were quiet for foreigners. Far from universally hostile, “in fact in many districts the natives were very friendly,” Davidson observes of this period.

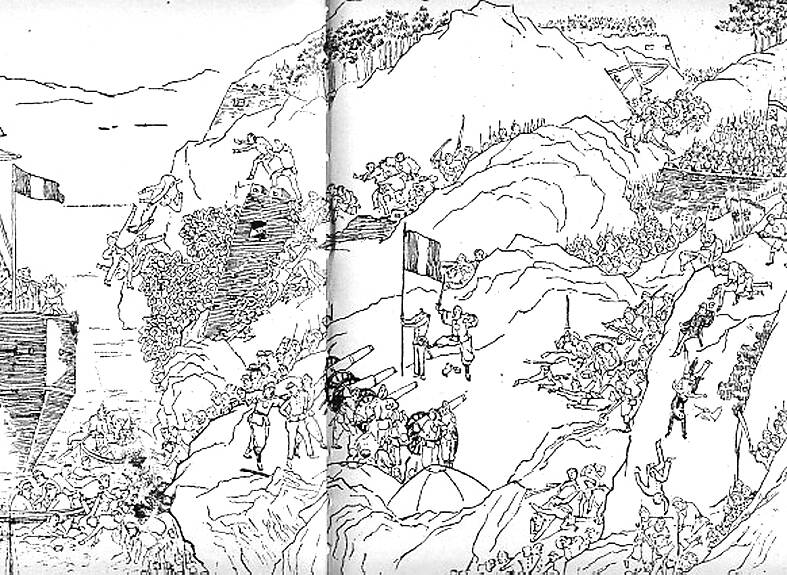

Not until the French invasion would there be extensive troubles for the churches. In October of 1884 there were attacks on churches amid accusations that Christians were cooperating with the French invaders. One of Mackay’s churches was hit, five churches were destroyed and several Christians murdered. But the rioting was suppressed by the end of the month. After the war Liu Ming-chuan (劉銘傳), the provincial governor, had three people executed and gave 10,000 taels of silver to Mackay for damages.

In our moral frameworks of history, Mackay is rightfully celebrated for loving Taiwan and leaving a medical and educational legacy that continues to affect the island. By contrast, Lieutenant Gordon and his tiny band of marines have been forgotten, or when remembered, contemptuously dismissed as “gunboat diplomacy.” Such discourses ignore how the Manchus came into possession of Taiwan in the first place.

But how could Mackay have done anything at all, without the threat of gunboats behind him?

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a