A group of Uyghur friends are having a late-night chat. “I wish the Chinese would just conquer the world,” one says suddenly. “Why do you say that?” another asks, surprised. “The world doesn’t care what happens to us,” the first man replies. “Since we can’t have freedom anyway, let the whole world taste subjugation. Then we would all be the same. We wouldn’t be alone in our suffering.”

It is an understandable outburst of bitterness. The Uyghurs are a Muslim minority who live mainly in China’s north-western Xinjiang region. They have long faced discrimination and persecution. Since 2016, the repression has greatly intensified, with mass detention, forced sterilization and abortion, the separation of thousands of children from their parents, and the razing of thousands of mosques. Yet support for Uighurs has been equivocal, not least from Muslim-majority countries, many of which are outraged by the burning of a Koran in Sweden but remain silent about the detention of more than 1 million Uighurs in Xinjiang, for fear of upsetting Beijing.

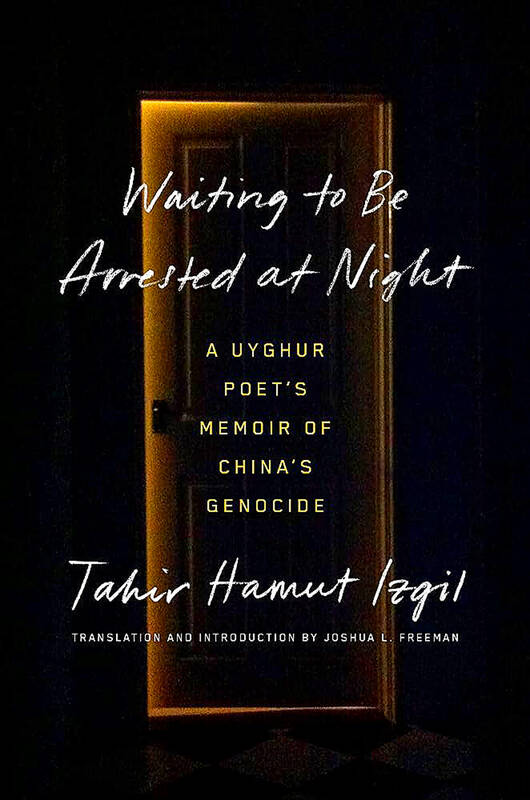

Tahir Hamut Izgil’s Waiting to Be Arrested at Night, which recounts that conversation, is not, however, a bitter book. It is suffused, rather, by a deep sense of sadness, and of despondency even amid hope.

“Yet our words could undo nothing here,/even the things we brought to be,” as one of Izgil’s poems laments.

A poet and film-maker, Izgil is famed for bringing a modernist sensibility to Uighur poetry. He did not set out to be a political activist. The very fact of being a Uighur, though, in a country that seeks to erase Uighur existence, both culturally and physically, turns everyday life into a political act. And for a poet living in a culture within which “verse is woven into daily life,” writing is necessarily also an act of witness and of resistance.

Despite the subtitle of the book — “A Uyghur Poet’s Memoir of China’s Genocide” — there are no depictions here of genocide, or of torture, or even of violence. We know all these things are happening, but off-page. Izgil’s memoir is a story about how to survive in, and to negotiate one’s way through, a society in which repression has become routine, and the power of the state is unfettered. The book’s restraint is also its strength. The tension in the narrative flows from the dread captured in the title — the dread of waiting to be arrested, to be vanished into detention, a dread no Uighur can escape.

Beijing’s strategy has been, over the past decade, to cut Uighurs off from the rest of the world and from one another, too. When censorship and surveillance made it impossible to link to the Internet beyond the Chinese firewall, many Uighurs took to keeping in touch with the outside world through shortwave radios. Until, that is, the government banned the sale of such radios and organized mass raids into people’s homes to confiscate them.

“We suddenly found ourselves living like frogs at the bottom of a well,” Izgil observes.

Beijing seeks to cut off Uighurs from their past and their traditions, too. Qur’ans are seized and history books banned, including many previously authorized by the state. Even personal names become part of the assault on Uighur culture. Beijing’s list of prohibited names tells Uighurs what they cannot call their children. Some names are apparently too “Muslim” — Aisha, Fatima, Saifuddin; others, such as Arafat, too political. When the list was first introduced, newspapers carried announcements such as: “My son’s birth name was Arafat Ablikim. From now on he will be known as Bekhtiyar Ablikim.”

The greatest dread is of the physical repression wreaked upon Uighurs: mass detentions, torture, violence. We get a glimpse of the horror when Izgil and his wife, Marhaba, attend a police station to have their biometric details collected — fingerprints, blood samples, facial scans. Along a basement corridor, they see a cell fitted out with iron restraints and a notorious “tiger chair,” used to force detainees into agonizing stress positions. On the floor are bloodstains.

People start disappearing, first in small numbers, eventually up to 1 million. They are taken to “study centres” — the code for mass detention camps — though nobody knows which one.

“They simply vanished,” Izgil writes.

The police knocked on the door when “your name was on the list.” There was, though, “no way to know if or when your name would show up on the list. We all lived within this frightening uncertainty.” It spawned a climate in which people feared one another as much as they feared the authorities.

Eventually, Tahir and Marhaba realize that their only option is to leave China. Emigration, though, is fiendishly difficult, especially for Uighurs, whose passports are held by the authorities. Somehow, they manage to negotiate the hurdles — though only after bribing doctors to certify one of their daughters as suffering from a form of epilepsy that has to be treated abroad. They escape to America to claim political asylum.

Relief at escape from tyranny is interwoven with the anguish of exile and of survivor’s guilt: “While we know the joy of those lucky few who boarded Noah’s ark, we live with the coward’s shame hidden in that word ‘escape.’” There is a sense of bleakness that bursts out in What Is It, Izgil’s first poem written after his escape to America: “These days/are crowded with shattered horizons,/shattered!” It is the pain of knowing that too many remain crushed by tyranny.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is