The vast state violence of the Japanese against Taiwan’s indigenous peoples, and their fierce resistance from their mountain strongholds, has largely disappeared from presentations on historical sites in today’s Taiwan.

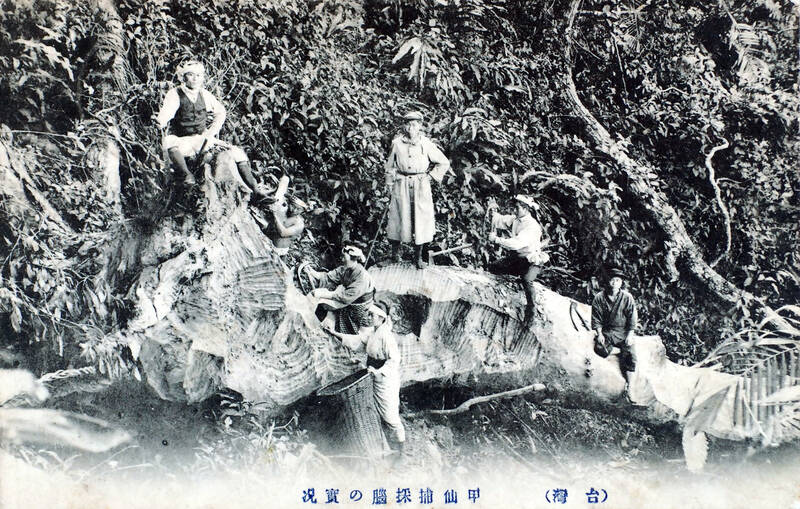

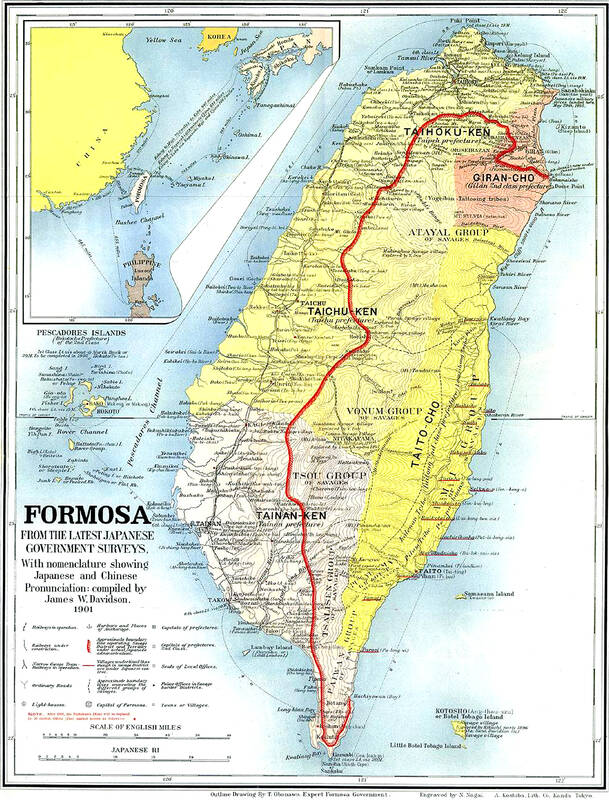

In an eye-opening PhD thesis, Toulouse-Antonin Roy writes: “Between 1895 and 1915, the Japanese empire waged hundreds of ‘pacification’ campaigns using police, military and paramilitary forces to bring the camphor-rich lands of indigenous Taiwanese under government control” (“The camphor question is in reality the savage question: The Japanese empire, indigenous peoples, and the making of capitalist Taiwan, 1895-1915,” UCLA, 2020).

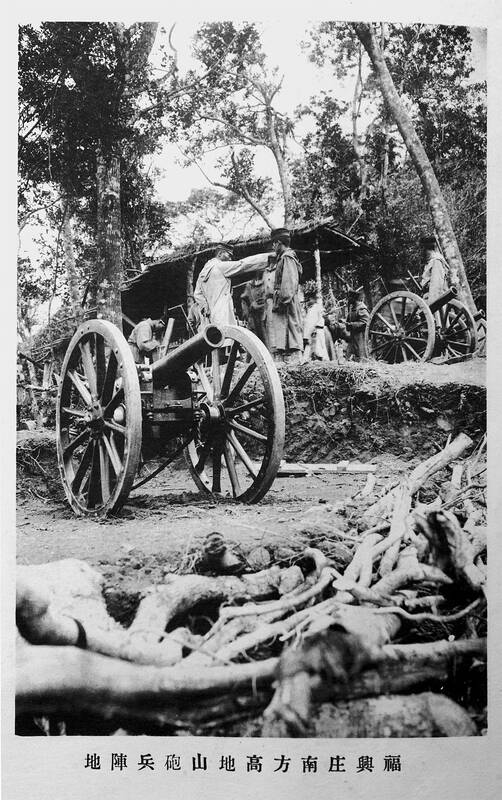

The savagery of the campaigns involved shelling villages from mountaintops, razing them and killing those who resisted while herding the remainder into villages to adopt sedentary agriculture.

Photo courtesy of National Museum of Taiwan History

Roy notes: “By the early 1900s, the Japanese Government-General had created a distinct type of expropriatory regime … in order to clear a path for extractive enterprises.”

This was driven by the demand for camphor production, especially in the north. Thousands of indigenous people died as a result.

WOOD FOR WARSHIPS

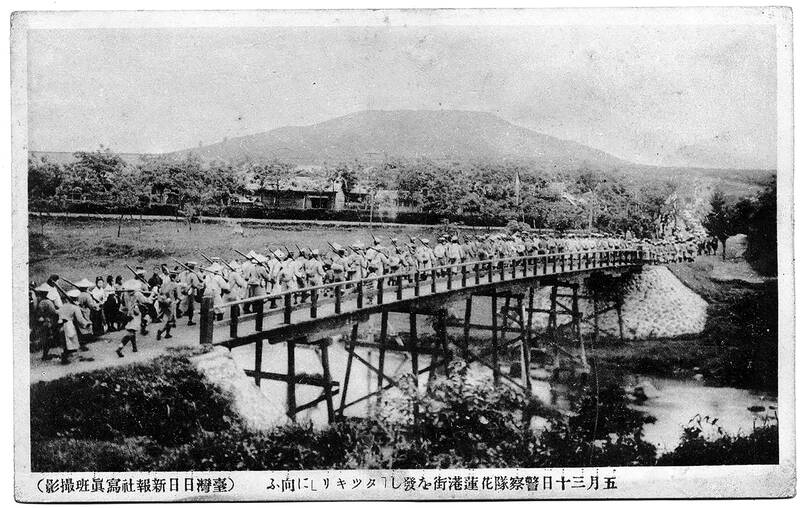

Photo courtesy of Hualien County Cultural Affairs Bureau

Global demand for camphor has long been presented in the literature on Taiwanese history as a key driver of demand for camphor trees in mountain areas, but during the Manchu Qing Dynasty, the trees had another important function: their wood was used to make warships.

Long before demand for camphor had begun to reshape the relations between the Han settlers, the imperial states that ruled them and the indigenous peoples of Taiwan, the Qing navy faced wood shortages for its burgeoning navy, especially after the Qianlong era.

The navy had grown out of the urgent need for ships to fight the Cheng state on Taiwan established by Koxinga (鄭成功). After the Manchus defeated the Chengs, peace reigned and pirates began to change their tactics, creating demand for more and faster ships to locate and fight them.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Culture Memory Bank

In 1825 a temporary shipyard was established in Taiwan. It produced warships until 1866, when production more or less halted. The yard was located in Tainan, near what is now the junction of Haian Road (海安路) and Chengkung Road (成功路).

The demand for camphor trees for ships drove the same cycle of extractive violence under the Manchus as it did for the Japanese, pitting indigenous peoples against each other. Forests at lower elevations had been repeatedly logged by the time the shipyards were established, pushing merchants and officials into higher elevations in search of suitable trees.

The naval need for wood was interrelated with the camphor market. Sourcing wood for ships themselves was unprofitable, so work gangs would not go into the mountains without the prospect of profits from camphor sales. Some crew leaders received monopolies on camphor production to encourage them to source wood for ships.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Culture Memory Bank

USING THE PINGPU

To carry out the mundane labor necessary for interactions with the mountains, the Manchu state used the Pingpu, or plains indigenous groups. Qing texts say that they were assigned to all sorts of menial tasks: carrying documents, digging ditches, hauling ships for launching, guarding mountain passes and accompanying officials on their forays into the mountains. Qing gazetteers aver that Pingpu people were put to hard labor at the age of 14. When they were assigned to escorts and a military clash occurred, they were always sent to the front. Naturally, they hated these duties.

The state also attempted to Sinicize the indigenous. As Katsuya Hirano, Lorenzo Veracini and Toulouse-Antonin Roy recount (“Vanishing natives and Taiwan’s settler-colonial unconsciousness,” 2018, Critical Asian Studies), in 1686 the local magistrate established four community schools in the indigenous districts of Sinkan, Bakloan, Soulang and Mattau around Tainan. Two years after the major revolt of 1731 against corvee labor, in which a Pingpu alliance laid siege to Changhua and were crushed with the loss of thousands of lives on both sides, the state established 47 schools in the western plains.

Indigenous peoples revolted repeatedly throughout the 18th and 19th century in response to corvee labor, land theft, and other issues. Typically they could be found on both sides of any conflict, as the Manchus deployed the plains peoples against the mountain peoples. In 1875 Shen Baozhen (沈葆楨) began the “open the mountains and pacify the savages” policy, of which Pingpu soldiers served an integral part. Liu Mingchuan (劉銘傳), the famed modernizing governor of Taiwan beginning in 1887, was an ardent supporter of this policy, and continued opening the mountains to Han settlement.

Doing so as Manchu power was beginning to wane had predictable results, as warfare between the encroaching state and its settlers and the indigenous peoples reached new heights. Then the Japanese came along with similar goals, but much better technology and organization.

TRIANGULAR RELATIONSHIP

Roy speaks of the “middle ground” during the Qing, a metaphor for the way settlers and indigenous and the state worked out their triangular relationship, such as the camphor stills worked by indigenous, or the payments made to indigenous groups to gain access to mountain resources. US diplomat Charles Le Gendre observed in 1867 Han farmers in Fangliao (枋寮) paying rent for using indigenous land, and indigenous people worked the trade on both sides between the mountains and the plains.

The Japanese disrupted these, leading to early revolts against them such as the bitter Nanzhuang Incident (南庄事件) in 1902 led by Ri Aguai (日阿拐), both Hakka and Saisayat elder. The shrinking middle ground was eviscerated by imperial violence against the locals.

Both the Manchu and Japanese empires depicted Taiwan as a place with an identifiable “civilized” area consisting of people willing to submit to imperial authority, and a “savage” area consisting of people unwilling to submit, in need of civilizing education so that they could enter into proper alignment with imperial power, learning to speak the imperial language and supply resources, goods, and manpower to it.

Today, in Taiwan, we all live in that second area, the empire across the water reaching across its frontier to smash all difference and make us submit.

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)