In the 1991 film Terminator 2: Judgment Day, a malevolent time-traveling and shape-shifting android called T-1000 that was made of liquid metal demonstrated a unique quality. Hit with blasts or bullets, its metal would heal itself.

Self-healing metal is still just science fiction, right?

Apparently not.

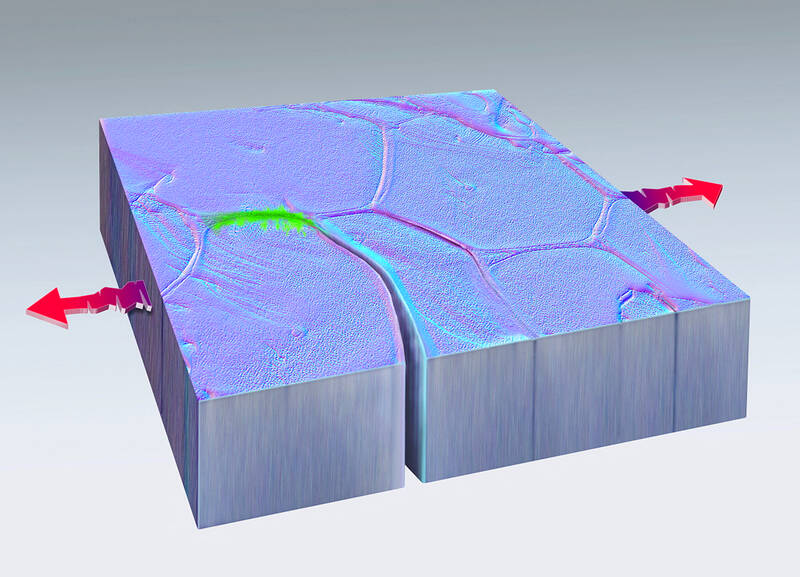

Photo: Dan Thompson/Sandia National Laboratories/Handout via Reuters

Scientists on Wednesday described how pieces of pure platinum and copper spontaneously healed cracks caused by metal fatigue during nanoscale experiments that had been designed to study how such cracks form and spread in metal placed under stress. They expressed optimism that this ability can be engineered into metals to create self-healing machines and structures in the relatively near future.

Metal fatigue occurs when metal — including parts in machines, vehicles and structures — sustains microscopic cracks after being exposed to repeated stress or motion, damage that tends to worsen over time. Metal fatigue can cause catastrophic failures in areas including aviation — jet engines, for instance — and infrastructure — bridges and other structures.

In the experiments at the US government’s Sandia National Laboratories in New Mexico, the researchers used a technique that pulled on the ends of the tiny metal pieces about 200 times per second. A crack initially formed and spread. But about 40 minutes into the experiment, the metal fused back together.

The researchers called this healing “cold welding.”

“The cold welding process is a metallurgical process that is known to occur when two relatively smooth and clean surfaces of metal are brought together to reform atomic bonds,” said Sandia National Laboratories materials scientist Brad Boyce, who helped lead the study published in the journal Nature.

“Unlike the self-healing robots in the Terminator movie, this process is not visible at the human scale. It occurs at the nanoscale, and we have yet to be able to control the process,” Boyce added.

Metal pieces were about 40 nanometers thick and a few micrometers wide. While the healing was observed in the experiments only in platinum and copper, Boyce said simulations indicated that self-healing can occur in other metals and that it is “entirely plausible” that alloys like steel could exhibit” this quality.

“It’s possible to envisage materials tailored to take advantage of this behavior,” Boyce said.

“Given this new knowledge, there may be alternative material design strategies or engineering approaches that could be devised to help mitigate fatigue failure. In addition, this new understanding may shed light on fatigue failure in existing structures — improving our ability to interpret and predict such failures,” Boyce added.

Scientists in the past have fashioned some self-healing materials, mostly plastics. Study co-author Michael Demkowicz, a Texas A&M University professor of materials science and engineering, predicted self-healing in metal a decade ago.

Demkowicz correctly figured that under certain conditions, putting metal under stress that ordinarily should worsen fatigue-related cracks could have the opposite effect.

“My guess now is that tangible applications of our findings will take another 10 years to develop,” Demkowicz said.

“When I first made my predictions, some of the press said I was working on a T-1000. That’s still sci-fi,” Demkowicz said.

“However, at the end of (TV series) Battlestar Galactica, the crew adapted some Cylon (a fictional robot race) technology to help heal fatigue damage to their ship, making metal behave more like an organic tissue that can heal its own wounds. I’d say what we’re working on is more along the lines of the Battlestar Galactica example.”

The self-healing was observed in a very specific environment using a device called an electron microscope.

“One of the big questions left open from the study is if the process also happens in air, not just the vacuum environment of the microscope. But even if it only occurs in vacuum, it still has important ramifications for fatigue in space vehicles, or fatigue associated with subsurface cracks that are not exposed to atmosphere,” Boyce said.

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

This year will go down in the history books. Taiwan faces enormous turmoil and uncertainty in the coming months. Which political parties are in a good position to handle big changes? All of the main parties are beset with challenges. Taking stock, this column examined the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) (“Huang Kuo-chang’s choking the life out of the TPP,” May 28, page 12), the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) (“Challenges amid choppy waters for the DPP,” June 14, page 12) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) (“KMT struggles to seize opportunities as ‘interesting times’ loom,” June 20, page 11). Times like these can

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend