I well remember from over 10 years ago, a man of around 30 walking into my Taipei apartment with three books he’d like considered for review in the Taipei Times.

It transpired he was a Canadian professor of literature teaching in the National Central University in Chungli. We got talking, and he indeed had an extraordinary tale to tell, of drunken orgies, fights and at least one death. His area, he said, was nothing like well-mannered Taipei. The Taipei Times eventually ran my conversation with him as an interview with “a professor with a fighting chance.”

The books proved fascinating, but very strange. I reviewed two of them, and others were to follow. I decided he was talented but eccentric and called him Taiwan’s Samuel Beckett.

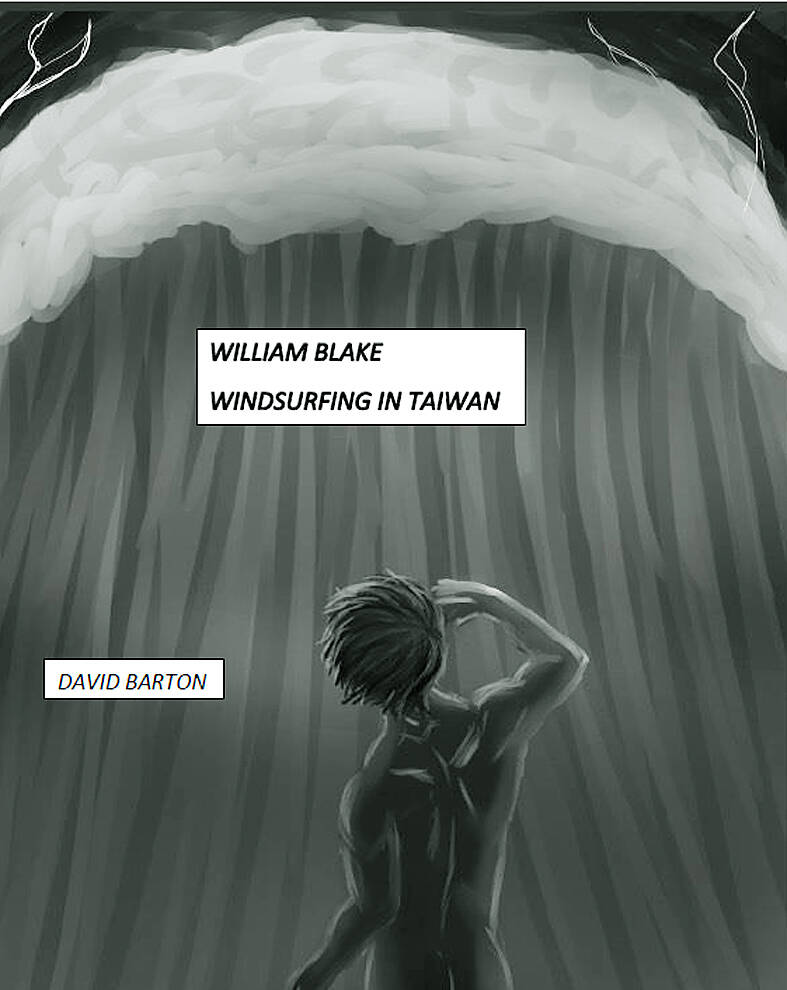

His name is David Barton and he has now come up with another book, this time based on the “prophetic books” of the English Romantic poet William Blake. These are works that have baffled even the most erudite Blake scholars, so much so that they are frequently omitted from accounts of the poet. They can be seen under the titles Jerusalem, Milton, The Four Zoas, and more.

The poet John Milton, incidentally, was something of a hero in the Romantic era in which Blake lived — a champion of free speech and of republicanism. Blake’s own views were paradoxical by any standards, opposing 18th century rationalism (“the Enlightenment”) and a believer in a Christianity of a very unusual kind.

Barton’s book begins with windsurfing in Guanyin on Taiwan’s northwest coast, and elaborate references to the 50 pages of illustrated text of Milton and the 100 pages of Jerusalem. People are seen as having been taken over by a scientific objectivity, whereas Blake preferred a world dominated by angels (“elohim”).

“When the sun rises, do you not see a round disc of fire, somewhat like a guinea?” “No! No!” replies Blake. “I see an innumerable company of the heavenly host crying ‘Holy, holy, holy is the Lord God almighty.”

Blake was considered mad, and that he wasn’t locked up was largely due, writes Barton, to the intercession of uncomprehending friends.

This is a wonderful idea for a book, combining the wild loneliness of windsurfing and the one-of-a-kind eccentricity of William Blake.

“Blake is a windsurfer of this oldest Chaos, the Ocean, as was his teacher, John Milton” writes Barton. “For Taiwan, China is that spectral illusion, Satanic and looming. Grotesque Giant or Snake looking for its Taiwan to swallow.”

Unfortunately, the Taiwan Strait (the ‘Black Strait’) is now brown and nearly dead. Blake windsurfs in a nasty chemical wash, a toilet bowl of toxic mud where one avoids a razor-sharp dead reef that shows its teeth at low tide.”

Barton in fact creates his own Guanyin mythology, complete with a contempt for reason, plus the Ocean and the Big Bang 14 billion years ago.

This is undoubtedly Barton’s best book. Teaching Inghelish in Taiwan (2001) was funny, and Saskatchewan (2010) had its own special atmosphere. But this new book has the huge advantage of combining two apparently irreconcilable subjects, to magnificent effect.

This is not to say I understand it all. But the same could be said of Blake’s prophetic books, though not of Milton.

“I was brought to windsurfing in Taiwan by the wreckage and chaos of a previous life, my first 15 years in Taiwan, a professor of 17th and 18th century literature and a bar owner.”

This being Barton, there’s a wide range of literary references, combined with doodles and abstract or impressionist paintings. There are also aphorisms galore — the ocean as a raging alcoholic, Nietzsche showing the way to Lao Tze, Blake’s Fleas that suck the life out of the Fly (and windsurfers), Rumpelstiltskin and a riddle in chemicals, copper and ink.

Meanwhile Barton is plagued by a giant wolf spider, “about hand size,” when four-meter waves keep him from windsurfing. But Los, one of Blake’s heroes, will be out there whatever the weather.

Barton follows in the tradition of seeing Milton as of the Devil’s party without knowing it: “Milton’s City in Hell, Pandemonium, is far more believable than anything the great poet could imagine in Heaven.”

Los was, in Blake, the embodiment of inspiration and creativity, whereas Urizen was reason and, hence, science and industrialism.

The view that Milton’s God was a bully was adopted by the great critic William Empson in Milton’s God (1961).

Barton doesn’t lay out his Blakean world in any formal way. Instead, you have to piece it together from Barton’s impressionistic fragments, often inspired though they are. “Tell me that Blake isn’t Darwinian,” Barton writes. “But funnier.”

In some ways this book is an anthology of fragments from some of Barton’s favourite creative intellects — Wallace Stevens, Iggy Pop, Bob Marley, Monty Python, Alexander Pope, David Lynch, Jimmy Hendrix and Charlie Parker.

A word needs to be said about the illustrations. Some squiggles, other photographs of the shoreline, or of monstrosities such as the Linko Power Station, coal-fired and “a massive beast.”

It appears Barton was given a year’s university sabbatical to write this book. Don’t read it if you want to understand all of Blake or all of Barton, though some information can be gleaned. Both authors could be considered a little mad on an uncharitable view. But as Barton puts it, “which of Blake’s Visions is not a pathological hallucination?”

Barton is a cultural guru to his fingertips, though he aspires to be something else as well.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she