Every year in Benin, locals celebrate a festival in tribute to the deities of Voodoo, the indigenous religion worshipping natural spirits and revering their ancestors.

Increasingly, the festival is drawing people of African descent from America, Brazil and the Caribbean seeking to discover the religion and land of their ancestors enslaved and shipped away from the beaches of west Africa. Voodoo, known locally as Vodoun, originated in the Dahomey kingdom — present-day Benin and Togo — and is still widely practiced sometimes alongside Christianity in coastal towns like Ouidah, once a trading hub where memorials to the slave trade are dotted around the small beach settlement.

“We come here first to search for our origins and reconnect with Mother Earth,” said Louis Pierre Ramassamy, 45, from Guadaloupe who was in Benin for the first time and visiting Ouidah.

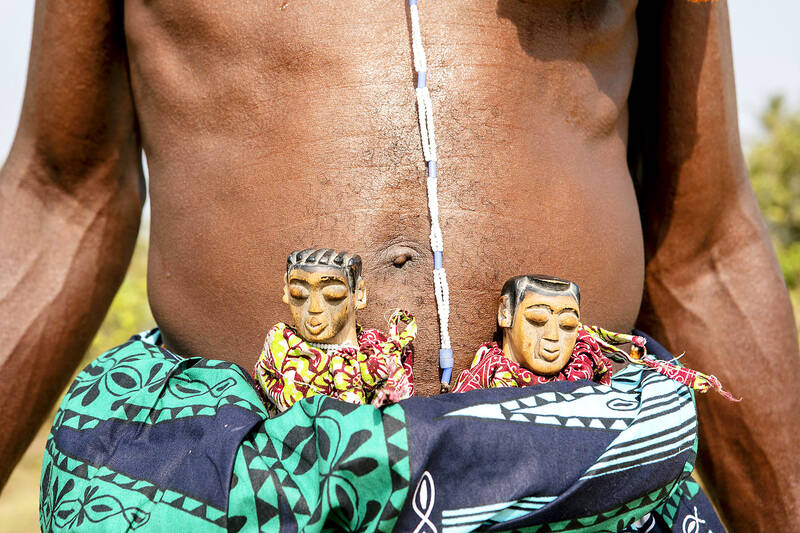

Photo: AFP

He came to discover the Vodoun festival, but his stay goes beyond that.

He said he wants to follow the footsteps of his ancestors, who were taken from Ouidah centuries ago and to rediscover the divinity practiced by his maternal grandmother. Consultations and sacrifices were made for him in a Vodoun convent in Ouidah to help him reconnect, he said.

“If luck does not smile on me this time, I will come back another time. I need this reconnection for my personal development,” the tourist said, his camera focused on the movement of voodoo practitioners on Ouidah’s imposing Atlantic Ocean beach.

Photo: AFP

Dozens of followers dressed in white cloth face the ocean each festival to pay homage in Ouidah to Mami Wata, a goddess of the sea.

Accompanied by drums and dancing, followers dressed in colorful traditional robes and gowns watched “Zangbeto” rituals — whirling dancers dressed as guardians of the night.

Nearby is an arch, the “Door of No Return,” in memory of those jammed onto slave ships from Ouidah’s beach bound for the New World.

Photo: AFP

“Our ancestors foresaw this return of Afro-descendants. They are eagerly awaited by the ghosts of our ancestors,” said Hounnongan Viyeye Noumaze Gbetoton, one of the Vodoun dignitaries in Ouidah. “When they return, it is to take blessings and recharge their batteries to move forward.”

Brazilian Anaica Durand said she had passed this stage. She managed to reconnect with her family of origin, the family of Almeida from Benin and is delighted with it.

Jan. 10 has now become a moment of great festivity for her to revel in the songs, dances and celebrations around Vodoun.

‘TRUE IDENTITY’

Like her, Alexandra Bajeux is on her second stay in Ouidah. This year, she came to pay homage to the Snake deity Dan.

“All the consultations revealed that it was the cult of my ancestors,” she smiles, white loincloth tied at the waist.

The 29-year-old Haitian plans to settle in Ouidah to devote herself full-time to this religion.

“Dan is happiness and he is a source of wealth,” said the young woman who swears “to have finally found the happiness” that she lacked.

“Our major objective is that the indigenous culture never fades away... Sooner or later, all Afro-descendants will return to the fold. This is what our ancestors say,” said Hounnongan Viyeye Noumaze Gbetoton.

Francis Ahouissoussi, a Benin sociologist specializing in religious issues, explains this attachment of descendants of African slaves as “a natural need that they must fill.”

According to him, many Afro-descendants feel they “are in a permanent quest for their true identity,” part of which is addressed for some by the role of Vodoun. For Brazilian Ana Beatriz Akpedje Almeida it felt like she was connecting the deities she knew from Brazil and others and to her ancestors.

“I think most people from the diaspora can connect with this kind of knowledge,” she said. “Voodoo is a perspective about humanity.”

US visitor Chastyl said it was also her first time in Benin.

“I have seen so many divinities and a lot of dancing,” she said. “I don’t have any family here, they are all in the United States, but obviously somewhere, we are from here.”

The Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS) told legislators last week that because the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) are continuing to block next year’s budget from passing, the nation could lose 1.5 percent of its GDP growth next year. According to the DGBAS report, officials presented to the legislature, the 2026 budget proposal includes NT$299.2 billion in funding for new projects and funding increases for various government functions. This funding only becomes available when the legislature approves it. The DGBAS estimates that every NT$10 billion in government money not spent shaves 0.05 percent off

Dec. 29 to Jan. 4 Like the Taoist Baode Temple (保德宮) featured in last week’s column, there’s little at first glance to suggest that Taipei’s Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會) has Indigenous roots. One hint is a small sign on the facade reading “Ketagalan Presbyterian Mission Association” — Ketagalan being an collective term for the Pingpu (plains Indigenous) groups who once inhabited much of northern Taiwan. Inside, a display on the back wall introduces the congregation’s founder Pan Shui-tu (潘水土), a member of the Pingpu settlement of Kipatauw, and provides information about the Ketagalan and their early involvement with Christianity. Most

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was out in force in the Taiwan Strait this week, threatening Taiwan with live-fire exercises, aircraft incursions and tedious claims to ownership. The reaction to the PRC’s blockade and decapitation strike exercises offer numerous lessons, if only we are willing to be taught. Reading the commentary on PRC behavior is like reading Bible interpretation across a range of Christian denominations: the text is recast to mean what the interpreter wants it to mean. Many PRC believers contended that the drills, obviously scheduled in advance, were aimed at the recent arms offer to Taiwan by the

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in