Scientists have successfully implanted and integrated human brain cells into newborn rats, creating a new way to study complex psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia and autism, and perhaps eventually test treatments.

Studying how these conditions develop is incredibly difficult — animals do not experience them like people, and humans cannot simply be opened up for research.

Scientists can assemble small sections of human brain tissue made from stem cells in petri dishes, and have already done so with more than a dozen brain regions.

Photo: AFP

But in dishes, “neurons don’t grow to the size which a human neuron in an actual human brain would grow,” said Sergiu Pasca, the study’s lead author and professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University.

And isolated from a body, they cannot tell us what symptoms a defect will cause.

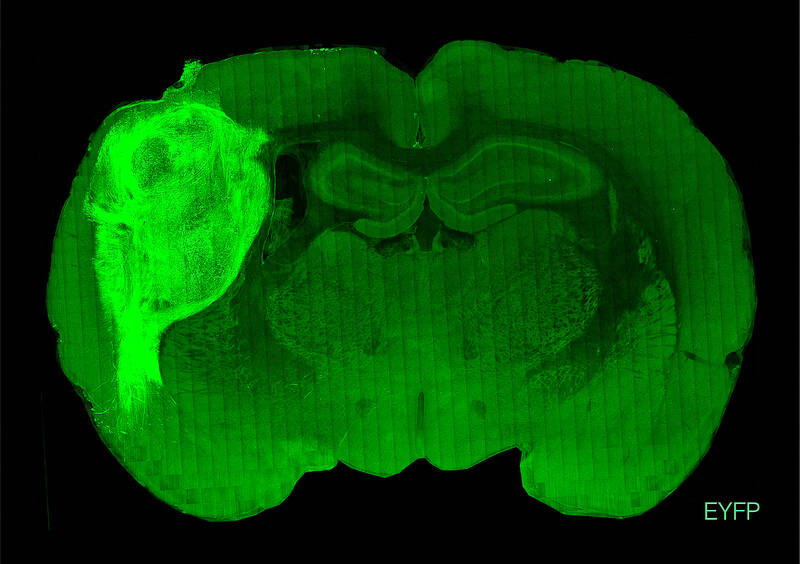

To overcome those limitations, researchers implanted the groupings of human brain cells, called organoids, into the brains of young rats.

The rats’ age was important: human neurons have been implanted into adult rats before, but an animal’s brain stops developing at a certain age, limiting how well implanted cells can integrate.

“By transplanting them at these early stages, we found that these organoids can grow relatively large, they become vascularized (receive nutrients) by the rat, and they can cover about a third of a rat’s (brain) hemisphere,” Pasca said.

BLUE LIGHT ‘REWARD’

To test how well the human neurons integrated with the rat brains and bodies, air was puffed across the animals’ whiskers, which prompted electrical activity in the human neurons.

That showed an input connection — external stimulation of the rat’s body was processed by the human tissue in the brain.

The scientists then tested the reverse: could the human neurons send signals back to the rat’s body?

They implanted human brain cells altered to respond to blue light, and then trained the rats to expect a “reward” of water from a spout when blue light shone on the neurons via a cable in the animals’ skulls.

After two weeks, pulsing the blue light sent the rats scrambling to the spout, according to the research published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

The team has now used the technique to show that organoids developed from patients with Timothy syndrome grow more slowly and display less electrical activity than those from healthy people.

Tara Spires-Jones, a professor at the University of Edinburgh’s UK Dementia Research Institute, said the work “has the potential to advance what we know about human brain development and neurodevelopmental disorders.”

But she noted the human neurons “did not replicate all of the important features of the human developing brain” and more research is needed to ensure the technique is a “robust model.”

ETHICAL DEBATES

Spires-Jones, who was not involved in the research, also pointed out potential ethical questions, “including whether these rats will have more human-like thinking and consciousness.”

Pasca said careful observations of the rats suggested the brain implants did not change them, or cause pain. “There are no alterations to the rats’ behavior or the rats’ well-being... there are no augmentations of functions,” he said.

He argued that limitations on how deeply human neurons integrate with the rat brain provide “natural barriers” that stop the animal from becoming too human. Rat brains develop much faster than human ones, “so there’s only so much that the rat cortex can integrate,” he said.

But in species closer to humans, those barriers might no longer exist, and Pasca said he would not support using the technique in primates for now.

He believes though that there is a “moral imperative” to find ways to better study and treat psychiatric disorders.

“Certainly the more human these models are becoming, the more uncomfortable we feel,” he said.

But “human psychiatric disorders are to a large extent uniquely human. So we’re going to have to think very carefully... how far we want to go with some of these models moving forward.”

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Snoop Dogg arrived at Intuit Dome hours before tipoff, long before most fans filled the arena and even before some players. Dressed in a gray suit and black turtleneck, a diamond-encrusted Peacock pendant resting on his chest and purple Chuck Taylor sneakers with gold laces nodding to his lifelong Los Angeles Lakers allegiance, Snoop didn’t rush. He didn’t posture. He waited for his moment to shine as an NBA analyst alongside Reggie Miller and Terry Gannon for Peacock’s recent Golden State Warriors at Los Angeles Clippers broadcast during the second half. With an AP reporter trailing him through the arena for an