The publication of Bill McGuire’s latest book, Hothouse Earth, could not be more timely. Appearing in the shops this week, it will be perused by sweltering customers who have just endured record high temperatures and now face the prospect of weeks of drought to add to their discomfort.

And this is just the beginning, insists McGuire, who is emeritus professor of geophysical and climate hazards at University College London. As he makes clear in his uncompromising depiction of the coming climatic catastrophe, we have — for far too long — ignored explicit warnings that rising carbon emissions are dangerously heating the Earth. Now we are going to pay the price for our complacency in the form of storms, floods, droughts and heatwaves that will easily surpass current extremes.

The crucial point, he argues, is that there is now no chance of us avoiding a perilous, all-pervasive climate breakdown. We have passed the point of no return and can expect a future in which lethal heatwaves and temperatures in excess of 50 degrees Celsius are common in the tropics; where summers at temperate latitudes will invariably be baking hot, and where our oceans are destined to become warm and acidic.

Photo: AFP

“A child born in 2020 will face a far more hostile world that its grandparents did,” McGuire says.

In this respect, the volcanologist, who was also a member of the UK government’s Natural Hazard Working Group, takes an extreme position. Most other climate experts still maintain we have time left, although not very much, to bring about meaningful reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. A rapid drive to net zero and the halting of global warming is still within our grasp, they say.

‘CLIMATE APPEASEMENT’

Photo: AFP

Such claims are dismissed by McGuire.

“I know a lot of people working in climate science who say one thing in public but a very different thing in private. In confidence, they are all much more scared about the future we face, but they won’t admit that in public. I call this climate appeasement and I believe it only makes things worse. The world needs to know how bad things are going to get before we can hope to start to tackle the crisis.”

McGuire finished writing Hothouse Earth at the end of last year. He includes many of the record high temperatures that had just afflicted the planet. A few months after he completed his manuscript, and as publication loomed, he found that many of those records had already been broken. “That is the trouble with writing a book about climate breakdown,” says McGuire. “By the time it is published it is already out of date. That is how fast things are moving.”

Wildfires of unprecedented intensity and ferocity have swept across Europe, North America and Australia this year, while record rainfall in the midwest led to the devastating flooding in the US’s Yellowstone national park.

“And as we head further into 2022, it is already a different world out there,” he adds. “Soon it will be unrecognizable to every one of us.”

These changes underline one of the most startling aspects of climate breakdown: the speed with which global average temperature rises translate into extreme weather.

“Just look at what is happening already to a world which has only heated up by just over one degree,” says McGuire. “It turns out the climate is changing for the worse far quicker than predicted by early climate models. That’s something that was never expected.”

CONSEQUENCES

Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, when humanity began pumping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, global temperatures have risen by just over 1 degrees Celsius. At the Cop26 climate meeting in Glasgow last year, it was agreed that every effort should be made to try to limit that rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius, although to achieve such a goal, it was calculated that global carbon emissions will have to be reduced by 45 percent by 2030.

“In the real world, that is not going to happen,” says McGuire. “Instead, we are on course for close to a 14 percent rise in emissions by that date — which will almost certainly see us shatter the 1.5 degrees Celsius guardrail in less than a decade.”

And we should be in no doubt about the consequences. Anything above 1.5 degrees Celsius will see a world plagued by intense summer heat, extreme drought, devastating floods, reduced crop yields, rapidly melting ice sheets and surging sea levels. A rise of 2 degrees Celsius and above will seriously threaten the stability of global society, McGuire argues. It should also be noted that according to the most hopeful estimates of emission cut pledges made at Cop26, the world is on course to heat up by between 2.4 degrees Celsius and 3 degrees Celsius.

From this perspective it is clear we can do little to avoid the coming climate breakdown. Instead we need to adapt to the hothouse world that lies ahead and to start taking action to try to stop a bleak situation deteriorating even further, McGuire says.

As to the reason for the world’s tragically tardy response, McGuire blames a “conspiracy of ignorance, inertia, poor governance and obfuscation and lies by climate change deniers that has ensured that we have sleepwalked to within less than half a degree of the dangerous 1.5 degrees Celsius climate change guardrail. Soon, barring some sort of miracle, we will crash through it.”

The future is forbidding from this perspective, though McGuire stresses that if carbon emissions can be cut substantially in the near future, and if we start to adapt to a much hotter world today, a truly calamitous and unsustainable future can be avoided.

“This is a call to arms,” he says. “So if you feel the need to glue yourself to a motorway or blockade an oil refinery, do it. Drive an electric car or, even better, use public transport, walk or cycle. Switch to a green energy tariff; eat less meat. Stop flying; lobby your elected representatives at both local and national level; and use your vote wisely to put in power a government that walks the talk on the climate emergency.”

In late October of 1873 the government of Japan decided against sending a military expedition to Korea to force that nation to open trade relations. Across the government supporters of the expedition resigned immediately. The spectacle of revolt by disaffected samurai began to loom over Japanese politics. In January of 1874 disaffected samurai attacked a senior minister in Tokyo. A month later, a group of pro-Korea expedition and anti-foreign elements from Saga prefecture in Kyushu revolted, driven in part by high food prices stemming from poor harvests. Their leader, according to Edward Drea’s classic Japan’s Imperial Army, was a samurai

The following three paragraphs are just some of what the local Chinese-language press is reporting on breathlessly and following every twist and turn with the eagerness of a soap opera fan. For many English-language readers, it probably comes across as incomprehensibly opaque, so bear with me briefly dear reader: To the surprise of many, former pop singer and Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) ex-lawmaker Yu Tien (余天) of the Taiwan Normal Country Promotion Association (TNCPA) at the last minute dropped out of the running for committee chair of the DPP’s New Taipei City chapter, paving the way for DPP legislator Su

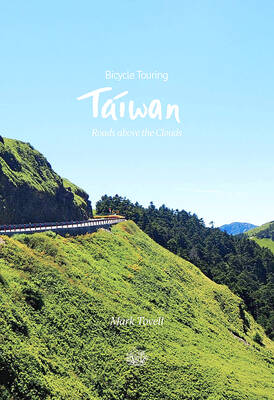

It’s hard to know where to begin with Mark Tovell’s Taiwan: Roads Above the Clouds. Having published a travelogue myself, as well as having contributed to several guidebooks, at first glance Tovell’s book appears to inhabit a middle ground — the kind of hard-to-sell nowheresville publishers detest. Leaf through the pages and you’ll find them suffuse with the purple prose best associated with travel literature: “When the sun is low on a warm, clear morning, and with the heat already rising, we stand at the riverside bike path leading south from Sanxia’s old cobble streets.” Hardly the stuff of your

Located down a sideroad in old Wanhua District (萬華區), Waley Art (水谷藝術) has an established reputation for curating some of the more provocative indie art exhibitions in Taipei. And this month is no exception. Beyond the innocuous facade of a shophouse, the full three stories of the gallery space (including the basement) have been taken over by photographs, installation videos and abstract images courtesy of two creatives who hail from the opposite ends of the earth, Taiwan’s Hsu Yi-ting (許懿婷) and Germany’s Benjamin Janzen. “In 2019, I had an art residency in Europe,” Hsu says. “I met Benjamin in the lobby