Although the three Chinese jiangsi (殭屍) in Tainan Art Museum’s “Ghosts and Hells: The Underworld in Asian art” are lauded as the main attraction, the painted latex figures were far from the most interesting part of the exhibit, which showcases various cultures’ conceptualizations of ghosts and the afterlife, in both traditional and contemporary art.

The reanimated corpses’ Qing Dynasty clothing is authentic, but the gray figures’ gaping mouths and outstretched hands evoked horror movie props — something that would be terrifying with dim lighting and VFX, but falls flat under a spotlight.

Instead, they’ve become the perfect photo-op, with groups lining up to mimic their poses with outstretched arms and rolled eyes.

Photo: Deanna Durben

The exhibition opens with a stunning fiber arts version of an altar with twisted and decapitated corpses, against a white calligraphed backdrop by acclaimed multi-media artist and scholar Yan Chung-hsien (顏忠賢). It’s the sort of cavernous space that would inspire hushed amazement, if not for the surging chattering crowd.

Crocheted red yarn hangs from white cloth skeletons, which are charmingly pillowy despite their macabre nature. Drawn-on grimaces depict cartoonish suffering on semi-abstract bodies that somehow convey a sense of deformed torsion.

Besides the dubious addition of a fear mongering folk story about indigenous people engaging in cannibalism, the various video displays throughout the exhibit served as useful supplementary info.

Photo: Deanna Durben

Movie clips of kitschy old ghost films from various countries brought the monsters on framed movie posters to life, while others compiled footage of ceremonial sites and statues.

Different rooms showcased different cultures, from Thai Phai specters to Japanese Edo period ghosts. The exhibition highlights different influences on Taiwanese culture, such as how Japanese ghosts created our typical imaginings of ghosts as pale, floaty and long-haired. However, I would have appreciated more explicit and in-depth explanations, so I could walk away with a more complete understanding.

A Thai display of amulets for Spirit Kumanthong were fascinating. Skeletal bronze figures stared out in childlike poses, some with hair or cloth wrappings. One red-caped figure looked just like Dr Strange in the denouement of Multiverse of Madness. Unfortunately, there wasn’t a clear explanation of the statuettes’ purpose either, so that remains the main association in my mind.

Photo: Deanna Durben

I loved pouring over a series of paintings of 10 levels of Buddhist hell. It featured graphically detailed depictions of dismemberments, disembowelments and other tortures. The crimes get more serious as you progress through the levels, although some of the hierarchies, like committing fraud being worse than rape, seem strange to modern sensibilities.

The last section had a floor-to-ceiling display of clear houses by artist Chen Yun (陳云), each with a brightly clothed doll lying inside. A closer look, which required leaning over and viewing individual boxes from above, revealed that each represented a person that had committed suicide.

One inscription described a seven-year-old boy who had jumped from a hospital building, after accidentally hurting his mother’s feelings by being jealous of her wheelchair.

Photo: Deanna Durben

Unfortunately, before I could examine more figures, or ascertain the purpose of the display and whether they were based on real Taiwanese, everyone was ushered out by a museum worker.

Ticket time slots run on a strict 55-minute schedule. It’s enough time to look at each display, but it’s probably still a good idea to keep an eye on the clock, especially if you tend to lag behind the main crowd to get a better look.

Regardless, the intense whirlwind of Asian art and ghostly artifacts is well worth the trip, especially if you have a tinge of morbid fascination with death.

In late October of 1873 the government of Japan decided against sending a military expedition to Korea to force that nation to open trade relations. Across the government supporters of the expedition resigned immediately. The spectacle of revolt by disaffected samurai began to loom over Japanese politics. In January of 1874 disaffected samurai attacked a senior minister in Tokyo. A month later, a group of pro-Korea expedition and anti-foreign elements from Saga prefecture in Kyushu revolted, driven in part by high food prices stemming from poor harvests. Their leader, according to Edward Drea’s classic Japan’s Imperial Army, was a samurai

The following three paragraphs are just some of what the local Chinese-language press is reporting on breathlessly and following every twist and turn with the eagerness of a soap opera fan. For many English-language readers, it probably comes across as incomprehensibly opaque, so bear with me briefly dear reader: To the surprise of many, former pop singer and Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) ex-lawmaker Yu Tien (余天) of the Taiwan Normal Country Promotion Association (TNCPA) at the last minute dropped out of the running for committee chair of the DPP’s New Taipei City chapter, paving the way for DPP legislator Su

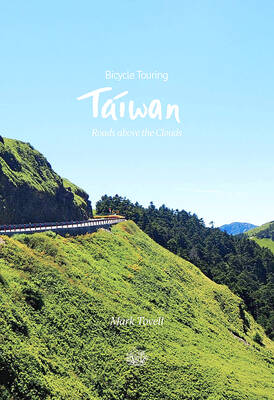

It’s hard to know where to begin with Mark Tovell’s Taiwan: Roads Above the Clouds. Having published a travelogue myself, as well as having contributed to several guidebooks, at first glance Tovell’s book appears to inhabit a middle ground — the kind of hard-to-sell nowheresville publishers detest. Leaf through the pages and you’ll find them suffuse with the purple prose best associated with travel literature: “When the sun is low on a warm, clear morning, and with the heat already rising, we stand at the riverside bike path leading south from Sanxia’s old cobble streets.” Hardly the stuff of your

Located down a sideroad in old Wanhua District (萬華區), Waley Art (水谷藝術) has an established reputation for curating some of the more provocative indie art exhibitions in Taipei. And this month is no exception. Beyond the innocuous facade of a shophouse, the full three stories of the gallery space (including the basement) have been taken over by photographs, installation videos and abstract images courtesy of two creatives who hail from the opposite ends of the earth, Taiwan’s Hsu Yi-ting (許懿婷) and Germany’s Benjamin Janzen. “In 2019, I had an art residency in Europe,” Hsu says. “I met Benjamin in the lobby