June 27 to July 3

“The Sacred Tree (神木) is on fire!” Tseng Tian-lai (曾添來) didn’t believe it at first as it was pouring rain, but he sensed the urgency in the caller’s voice. The Alishan Forest Railway station master stepped out and saw smoke billowing from the direction of the beloved 3,000-year-old red cypress.

The tree was struck by lightning in the afternoon of June 7, 1956, and a fierce blaze raged inside the eroded trunk, requiring nearly 200 people 20 hours to put it out. The authorities were especially nervous, according to a 1997 Liberty Times (Taipei Times’ sister paper) report, because they had built a pavilion next to the tree to wish then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) a long life on his 67th birthday. What would it symbolize if the tree died?

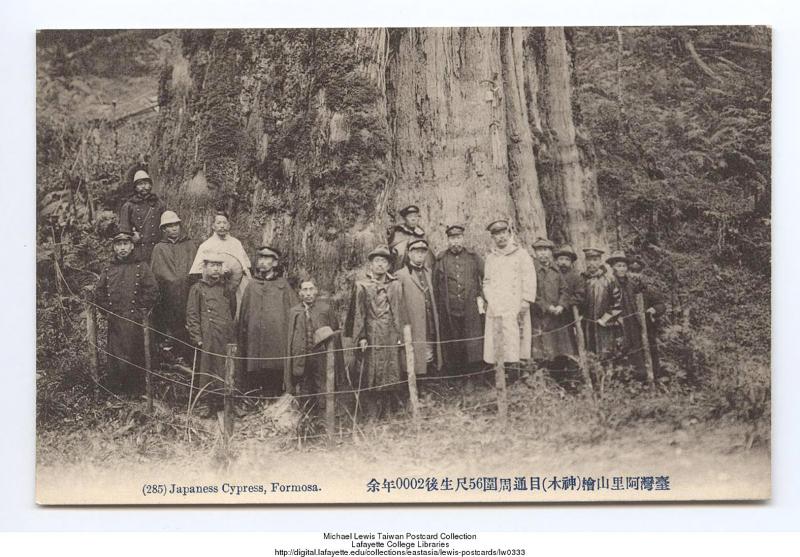

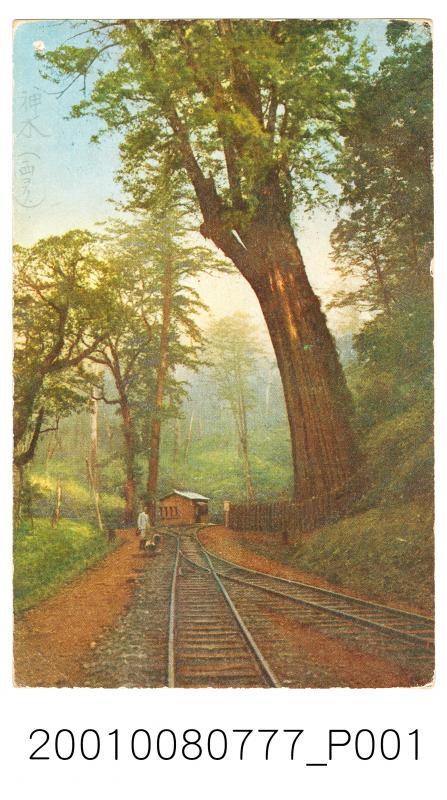

Photo courtesy of Lafayette Digital Repository

While the tree didn’t survive the fire, forestry workers kept it standing and planted red cypress saplings on the top of the towering trunk so that it appeared to still thrive. And it continued to be a famous tourist attraction until July 1, 1997, when half of it collapsed onto the adjacent train tracks during a heavy storm.

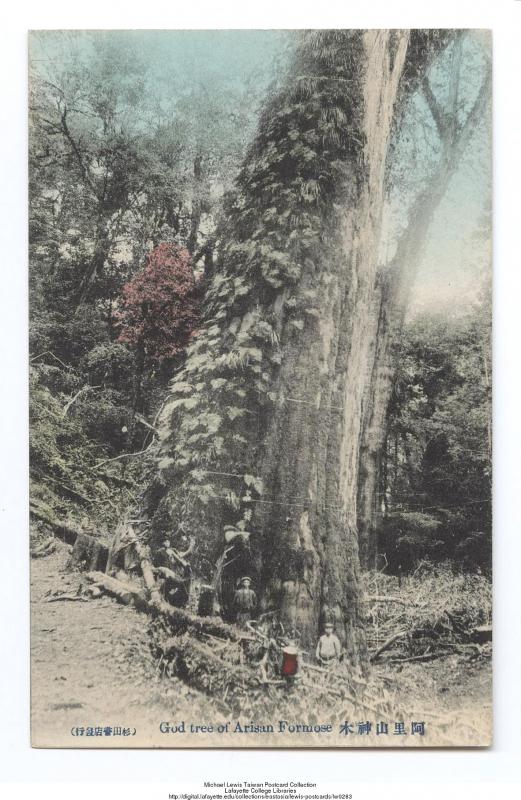

Today, “sacred trees” (神木) can refer to any red or yellow cypress that are over 1,000 years old. But for nearly a century, this was the Sacred Tree. The Japanese deemed it to be divine when they first saw it in 1906, and even though they heavily logged the surrounding area over the next few decades, they left the Sacred Tree alone.

After much deliberation and public discussion, the Forestry Bureau on June 29, 1998 made the painful decision to cut the giant down. Workers sawed through its base then severed the eight supporting steel wires one by one. The mostly-intact trunk was left where it fell.

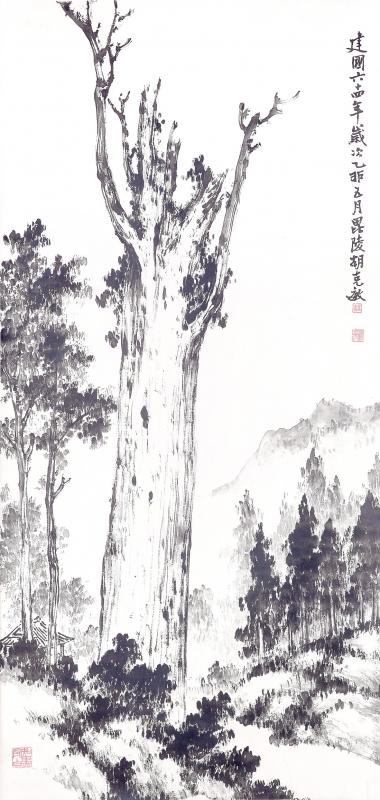

Photo courtesy of Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall

FELLING THE GIANTS

The Japanese noticed the quality forests in the Alishan area soon after they took over Taiwan in 1895. Growing slowly in a high-altitude area, the trees here provided exceptionally sturdy wood — with the Taiwanese red and yellow cypresses being the most valuable.

They sent several expeditions into the mountains over the years, often with indigenous Tsou guides. In 1906, Fujiro Ogasawara became the first Japanese to reach the Sacred Tree, which he deemed to be about 55m tall and 6m wide (later measurements reduced the height to 50m). There were many comparable behemoths in the area then, and the Japanese only marked three for preservation; the rest were all fair game to cut down. They built a protective fence around the Sacred Tree, and tied a Shinto shimenawa rope around it to signify its sanctity.

Photo courtesy of Lafayette Digital Repository

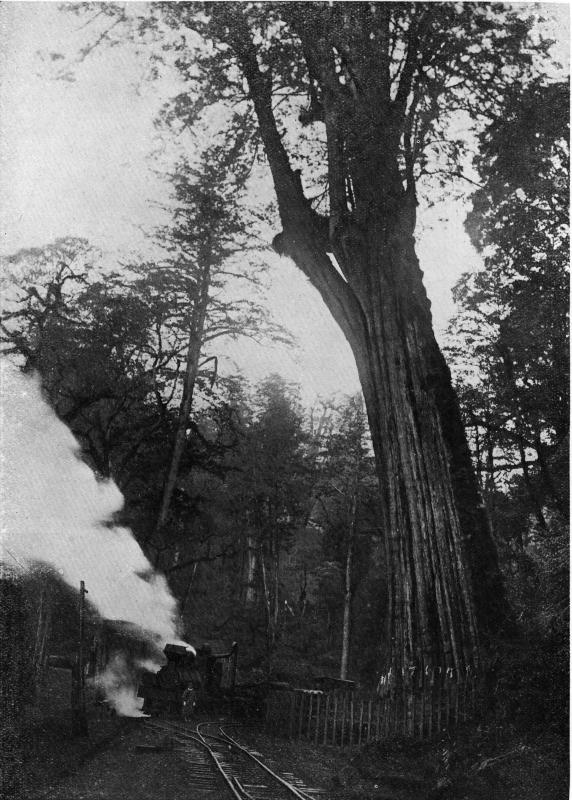

Logging began in 1912, and the Alishan Forest Railway line was completed in 1913 to transport timber down the mountain to processing and production facilities in Chiayi. With parts imported from the US, the state-of-the-art Chiayi Timber Factory started operating in December 1914, and at 162,417 ping, it was among the largest in East Asia.

Numerous private operations were opened along the railway, quickly turning Chiayi into a bustling “City of Cypress” (檜木町). The timber was coveted internationally, and between 1912 and 1945, an average of 44,808m3 of crude wood was shipped down the railroad. The Japanese felled so many trees that in 1935, they built a Tree Spirit Pagoda in the forest after workers began coming down with strange illnesses.

Sources indicate that cutting down surrounding trees increased the chances that the Sacred Tree would be struck by lightning. Logging in Alishan continued under the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and only stopped in 1965, after resources were mostly depleted.

Photo courtesy of Academia Sinica

RETURN TO NATURE

After the tree died in the 1956 fire, experts in 1962 planted seven saplings on a dirt-filled platform at the top of the tree. Some called this the “second generation Sacred Tree,” while others criticized the government for cheating tourists by creating a false impression that the tree was still alive.

In July 1994, the Forestry Bureau noticed that the crack in the tree’s trunk was widening and was in danger of collapsing. The Forestry Bureau met with local leaders the following May, and they concluded that the tree must not be removed due to it being the spiritual landmark of Alishan, as well as a top tourist draw.

Photo courtesy of National Museum of History

A complex plan was made to save it, including steel supports, filling in the hollow inside with cement and injecting it with cypress oil to slow decay. They also sought to promote nearby giant trees to divert foot traffic. The Sacred Tree was reduced in height to 35m after extensive damage, and several others in Alishan were now taller and larger.

“Taiwanese should turn their attention to the natural forest that we still have left to enjoy, instead of trying to revive a deceased tree,” environmentalist Chen Yu-feng (陳玉峰) argued in a China Times (中國時報) op-ed.

However, authorities refused to give up after the 1997 partial collapse. In a public survey, about 47 percent of respondents wanted to cut the whole tree down, but still display it in place, while another 50 percent hoped to keep it standing with reinforcements. The final decision was to cut off part of the top for public safety reasons and display part of the tree on the other side of the tracks.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

However, no company bid on the government’s contract, and in April 1998 The Society of Wilderness stepped in, holding a night vigil and petitioning the government to let the tree go. It was also costly to maintain the tree, and forcing it to stay upright would also endanger tourists as well as other trees.

“The Sacred Tree is a living being, and is thus subject to a natural life cycle. We humans should not use artificial means to forcefully resist nature,” the society stated. “It also sets a bad example for [environmental] education, as keeping the dead tree up will only prevent new life from growing. It is only delaying the inevitable.”

An intense debate ensued, and in June 1998, the joint committee decided the best course of action was to let the tree go.

“The demise of the Sacred Tree at the end of the 20th century should symbolize the end of the past two regimes’ foolish actions in aggressively decimating Taiwan’s natural forests,” Chen wrote.

“To those great spirits who have watched over Taiwan for the past 3,000 years, please deliver a message to every Taiwanese that they urgently need to develop awareness of and respect for nature.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.