Since moving from Taiwan’s capital to the outlying Penghu islands for the peace and the fishing 11 years ago, Lin Chih-cheng has grown accustomed to the roar of Chinese fighter jets puncturing the lull of the surf.

“If there’s a day where they don’t take off, it feels weird,” laughed Lin, an affable 61-year-old who runs a juice stall with his wife on the western Xiyu Islet.

The archipelago’s location about 50km out in the Taiwan Strait means it is likely to be on the front line of any potential invasion by China — a perennial possibility that has loomed ever larger in the last few years.

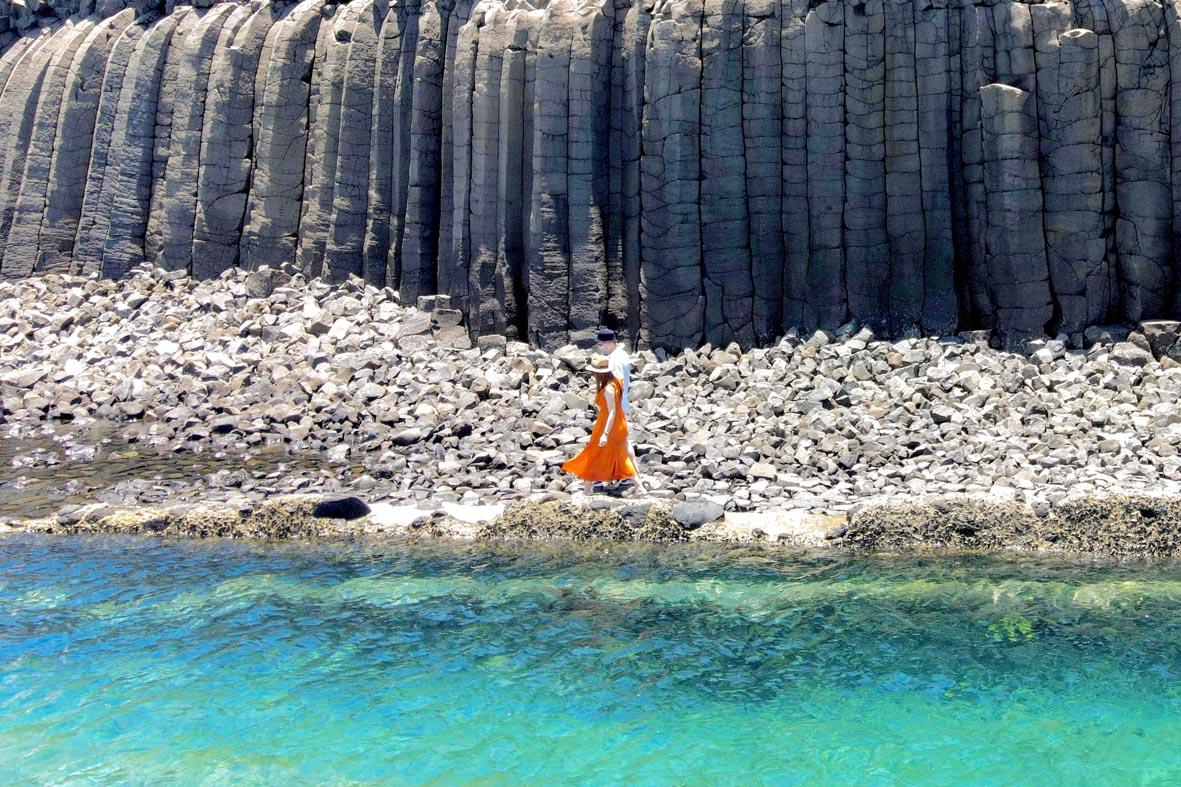

Photo: AFP

Beijing claims all of Taiwan as its territory, and its pledge to take it by force if necessary has begun to seem less farfetched as China projects an increasingly aggressive stance on the world stage. But in the sleepy fishing towns on the islands, many locals are sanguine despite the frequent — and noisy — reminders of the military threat.

“Everyone says tension between both sides is high now, but I am not worried,” said Lin. “I have confidence that our government is not beating the war drum.”

Xiyu’s azure waters and twisting, heart-shaped stone weirs have made it an Instagrammer’s paradise. Business is good at the juice stall, where Lin and his wife blend cactus fruit and ice flower into sweet, cold drinks for a stream of thirsty tourists. Just down the road are a very different set of customers — the soldiers at a Sky Bow base, home to Taiwan’s surface-to-air anti-ballistic missile and anti-aircraft defense systems.

Photo: AFP

“I actually do a lot of deliveries to the base,” Lin said. “I have been inside. It feels quite normal to me.”

The presence of troops has been a fact of life for decades on the island, where they are seen more as a source of income than one of dread.

“People from both sides (of the strait), we actually share the same language and culture,” Lin said. “Who wants war? We actually get along with each other. The affairs of those in power are none of our business.”

‘NOTHING WE CAN DO’

But Penghu has found itself at the mercy of geopolitical forces many times throughout its history. “Penghu is a hard-to-defend place,” said Chen Ing-jin, a 67-year-old local historian and architect. “It’s flat and has many coastal areas, which makes it very hard to prevent possible landings.”

The Dutch, French and Japanese all invaded with little trouble, and signs of war — past and present — are everywhere. The historic forts, now there for tourists rather than defense, have been replaced by serious modern firepower.

In addition to Sky Bow, the islands also harbor Hsiung Feng II anti-ship cruise missile bases — Chen helped build one of them during his military service. Xiyu also hosts a radar station that would give vital early warning of any planned attack.

Those are all reasons Beijing might choose to take the islands before any attempt on Taiwan’s main island in a bid to disable the military installments and gain a resupply base. Few locals think they would stand much chance against China’s People’s Liberation Army.

“Their ships will surround the islands and that will be it. There’s nothing we can do about it but accept,” said Chen’s friend, Wang Hsu-sheng.

‘VERY UNCOMFORTABLE’

Like many, Wang’s family history tracks the islands’ tumultuous changing of hands.

His father was put to work in naval yards under the Japanese occupation, and only returned to the family business — creating painstakingly detailed miniature paper deities for temples — after their withdrawal at the end of World War II. Wang, now 70, learned the craft from his dad, but calls it a “dying art” in this day and age. He said China’s actions over the last few years have made him “very uncomfortable.”

“The Chinese are like the Russians. What’s yours is mine. What’s mine is still mine,” he said, referencing the recent invasion of Ukraine.

Andy Huang, who runs an ice cream shop in the main town of Magong, has more experience than most in facing Beijing’s belligerence. A former coastguard, the 29-year-old was based in the South China Sea’s contested Spratly Islands when a “3,000-tonne Chinese coastguard ship was circling our island with their big guns pointing at us.”

He and his colleagues were ordered into their far smaller boats to drive it away, though a confrontation never materialized.

“I was really scared, scared of dying in a gunfight,” he said.

That brush with war seems far away today as he hands out icy treats to sunburned visitors. But Huang was clear he would fight to defend his home if need be.

“I would be one of the first to be called up to serve if war breaks out,” he said stoically. “But until that happens, life goes on.”

Taiwan has next to no political engagement in Myanmar, either with the ruling military junta nor the dozens of armed groups who’ve in the last five years taken over around two-thirds of the nation’s territory in a sprawling, patchwork civil war. But early last month, the leader of one relatively minor Burmese revolutionary faction, General Nerdah Bomya, who is also an alleged war criminal, made a low key visit to Taipei, where he met with a member of President William Lai’s (賴清德) staff, a retired Taiwanese military official and several academics. “I feel like Taiwan is a good example of

Institutions signalling a fresh beginning and new spirit often adopt new slogans, symbols and marketing materials, and the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) is no exception. Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文), soon after taking office as KMT chair, released a new slogan that plays on the party’s acronym: “Kind Mindfulness Team.” The party recently released a graphic prominently featuring the red, white and blue of the flag with a Chinese slogan “establishing peace, blessings and fortune marching forth” (締造和平,幸福前行). One part of the graphic also features two hands in blue and white grasping olive branches in a stylized shape of Taiwan. Bonus points for

“M yeolgong jajangmyeon (anti-communism zhajiangmian, 滅共炸醬麵), let’s all shout together — myeolgong!” a chef at a Chinese restaurant in Dongtan, located about 35km south of Seoul, South Korea, calls out before serving a bowl of Korean-style zhajiangmian —black bean noodles. Diners repeat the phrase before tucking in. This political-themed restaurant, named Myeolgong Banjeom (滅共飯館, “anti-communism restaurant”), is operated by a single person and does not take reservations; therefore long queues form regularly outside, and most customers appear sympathetic to its political theme. Photos of conservative public figures hang on the walls, alongside political slogans and poems written in Chinese characters; South

March 9 to March 15 “This land produced no horses,” Qing Dynasty envoy Yu Yung-ho (郁永河) observed when he visited Taiwan in 1697. He didn’t mean that there were no horses at all; it was just difficult to transport them across the sea and raise them in the hot and humid climate. “Although 10,000 soldiers were stationed here, the camps had fewer than 1,000 horses,” Yu added. Starting from the Dutch in the 1600s, each foreign regime brought horses to Taiwan. But they remained rare animals, typically only owned by the government or