June 13 to June 19

Despite Taiwan being famous for its oolong tea during the late Qing Dynasty, the Japanese hoped to turn its new colony into “another Darjeeling.” The suggestion was made by the Japanese consul to Mumbai, Go Daigoro, a year after they took over Taiwan in 1895.

Indian Black tea was gaining popularity on the international market after the British systematized and mechanized large scale production in the country’s northeast, causing a steep drop in sales of other varieties of tea from East Asia. Unorganized and uneven production in Taiwan — with many producers cutting corners to save costs — also plagued the local industry, leading the Japanese to install a number of reforms.

Photo: Chen Hsin-jen, Taipei Times

One goal was to successfully grow a variety of black tea that could compete with India. The effort began in 1906, and although most of the crop was exported to Russia and Turkey, the industry didn’t pick up until they discovered in the 1920s that Nantou County’s Yuchi Township (魚池) was an ideal growing location for Indian leaves.

A key person for this success was Kokichiro Arai, who arrived in Taiwan in 1926 and was instrumental in the establishment of the Yuchi Black Tea Research Institute (today’s Yuchi Branch of the Tea Research and Extension Station) on Maolan Mountain (貓?山) in 1936. He became the institute’s head in 1941, and continued to promote and develop the local Ceylon-style black tea despite limited resources during World War II.

Arai stayed on after the war to help the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), and is often remembered as the “guardian of Taiwan’s black tea.” He died from malaria on June 19, 1947, but the industry boomed over the years until its decline in the late 1960s.

Photo: CNA

After the devastating 921 Earthquake in 1999, local officials revived the industry in an effort to rebuild the area, and today Yuchi is once again famous for its black tea.

EARLY STRUGGLES

Although there had been small-scale production of black tea in Taiwan during the Qing Dynasty, local farmers prefered Oolong and other varieties. As international competition heated up during the early Japanese era, however, the prestige of Taiwanese tea started to slide. It was overly reliant on the US market, and suffered greatly during tightened restrictions during the Spanish-American War of 1898.

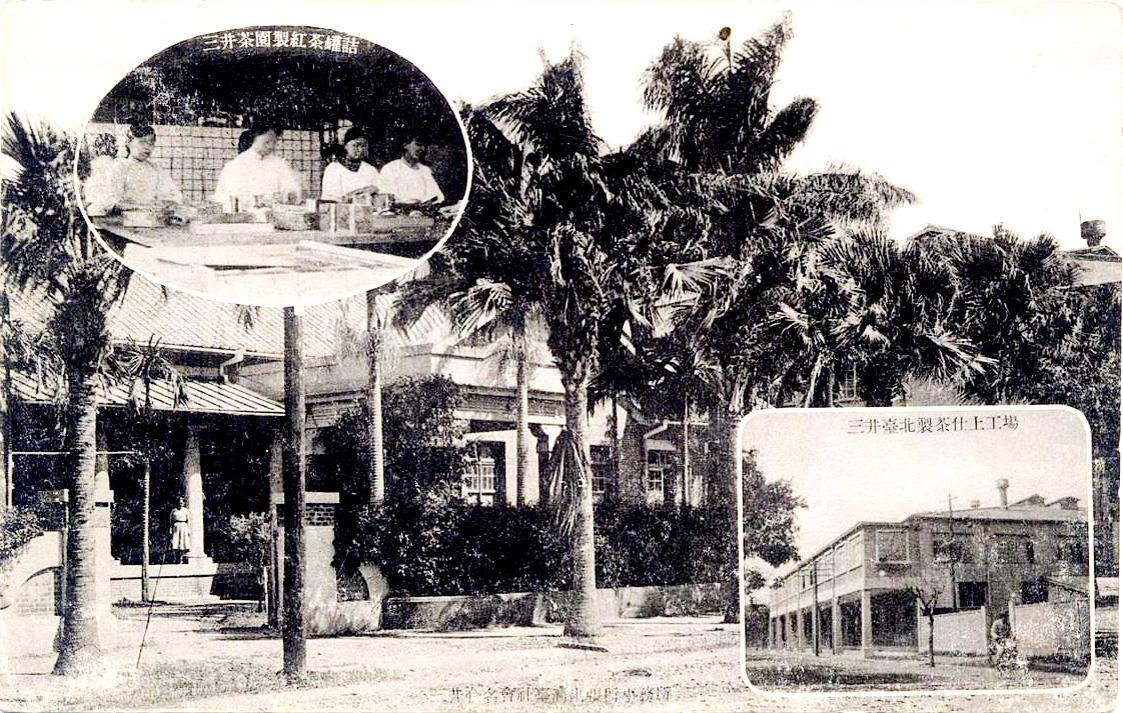

Photo courtesy of Lafayette College Libraries via Open Museum

Su Yu-ting (蘇郁婷) writes in “Marketing Channels and Sales of Taiwanese Black Tea during the Japanese Occupation” (日治時代台灣紅茶的外銷與品飲) that compared to the systematized production of India, Taiwan’s tea relied on manual labor and the goods were often uneven in quality. In 1909, a Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報) article blamed the shoddy transport crates, which often broke and spoiled the tea. About 100,000 boxes per year went to waste, the article stated. Fierce local competition also led producers to mix lower grade leaves or other fillers in with the higher-quality variety.

Another problem was that the trade was controlled by wealthy vendors and various middlemen, who gouged up the prices at the expense of farmers. The Japanese in 1901 launched a series of reforms that included organized production by Japanese corporations, mass mechanization and strict quality control.

“The decline of the tea industry is becoming more apparent in recent years,” newly-appointed governor-general Gentaro Kodama wrote in his proposal. “If we allow this to go on for a few more years, it will only continue to tragically decrease.”

The government originally hoped to promote oolong tea, showcasing it at the Paris Exposition of 1900. They opened a tea shop on the fairgrounds and kept a tally of which variety each customer chose, and to their surprise, 42 percent out of the 8,000 or so visitors went with black tea, compared to 28 percent for oolong.

The first research center dedicated to black tea was launched in 1903 what is today’s Taoyuan, using methods and machines imported from the UK. After the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, the Japanese noticed that the Russian POWs had a habit of drinking black tea. They let the imprisoned commanders try the Taiwanese-grown variety to great approval. Selling to Russia was a different story, however, and it would prove the same in other countries over the following decades.

SUCCESS IN YUCHI

At first, most of the larger-scale commercial farming of black tea took place in northern Taiwan by the Mitsui Corporation. They did find success, but it was becoming increasingly hard to compete with India and Sri Lanka. Additionally, northern Taiwan was not suitable for growing the Assam and Ceylon cultivars favored by Western tea-drinkers.

In 1926, the government successfully grew Assam black tea leaves in central Taiwan and noted that the quality was far superior to the local cultivars previously used. A 1933 Taiwan Daily News article extolled the environment of Yuchi, which had just the right altitude, climate and soil.

“In the future, black tea will surely become a specialty product of Taichu Prefecture,” it concluded, referring to what is today Taichung City and County, Changhua County and Nantou County.

Mitsui upgraded its equipment in 1928, and using Indian production methods, created the famous Nitto brand that still exists today.

Unfortunately, India that year banned the export of Assam leaves — which were pricey to begin with — to Taiwan to protect its own industry. This led to the creation in 1936 of the Yuchi Black Tea Research Institute, which focused on developing Assam varieties that could easily be mass-cultivated locally by hybridizing them with Taiwanese wild tea.

The institute also helped develop cultivars brought back from the Thai-Myanmar border by the adventurous “Black Tea Grandpa” Kuo Shao-san (郭少三), which became today’s Taiwan Tea No. 7.

Taiwan’s black tea took off from there, and in 1937 Mitsui’s Formosa Black Tea received high acclaim at a London auction and was enjoyed by the Japanese emperor. Over 5.8 million kilograms of black tea were exported that year. Kuo launched the Puli-based Tung Pang Black Tea Co (東邦) in 1939, and exported his products to Japan and the West. It was one of the businesses revived after the earthquake.

There’s not that much information about Arai’s time in Yuchi. But his dedication and willingness to stay after the war greatly moved new institute head Chen Wei-chen (陳為禎), who erected a monument to him on the institute’s grounds. Arai’s wife and two sons also died in Taiwan, and upon his death, his daughter Reiko returned to Japan and rarely discussed her father’s time here. Her husband and their children visited the monument for the first time in 2008.

The industry continued to do well and expanded under the KMT, but rising wages in the 1960s led to higher costs, and soon Taiwan was no longer able to compete internationally. Meanwhile, tea drinking, which had previously been limited to the wealthy, became a popular activity as the economy grew, but locals preferred oolong over black tea. The industry survived but shrank significantly, and many former fields were turned into betel nut farms.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades