“Circular economy” isn’t just a buzzword. Transforming the economy, so the emphasis is on recycling and reusing materials already in circulation, instead of extracting natural resources from the Earth, is a national goal.

As one of the planks of the “5+2 Major Innovative Industries” plan set out by President Tsai Ing-wen’s (蔡英文) administration, the push for a circular economy is expected to create a wealth of business opportunities, reduce Taiwan’s dependence on imported energy resources and raw materials and hopefully also curtail greenhouse-gas emissions and other forms of pollution for which the country is responsible.

Taiwan is making progress toward a circular economy on multiple fronts.

Photo courtesy of ITRI

Several of the country’s larger hog farms now convert pig manure into biogas which is then burned to generate electricity. The per kWh carbon footprint of biogas is greater than that of solar, wind or hydropower, but considerably smaller than that of fossil fuels including natural gas. According to Circular Taiwan Network’s Web site (circular-taiwan.org), biogas residuals could be used as fertilizer, adding nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium to fields. Currently, many of the inputs used to make fertilizer in Taiwan (including 100 percent of the uera) are imported.

As reported in this column two weeks ago (“Environmental Impact Assessment: Reducing Taiwan’s virgin plastics,” May 25, 2022), Taiwan’s world-class textiles industry turns flakes and pellets of plastic recycled from PET beverage bottles into apparel and footwear for global brands.

At the same time, innovators are working to close some less obvious gaps in the circular economy. One concerns a seafood-production technique that Taiwanese have been using for at least 300 years. The other is also connected to food, but wasn’t an issue until much more recently.

Photo: Steven Crook

OYSTER SHELLS

Oyster beds dot Taiwan’s west coast, especially in the southwest. The method by which oysters are raised hasn’t changed in generations. Old shells attached to grids made of bamboo poles attract oyster larvae (spat) which in turn are nourished by microscopic creatures carried in on the tide. The spat grow for four or five months, after which they’re mature enough to be harvested.

Because some oysters generate new shells, rather than inhabit old ones, Taiwan’s coastal villages end up with approximately 169,000 tonnes of oyster shells per year — far more than they can use in aquaculture.

Photo: Steven Crook

In the past, oyster shells were pulverized, burned and used as a cement. This use is unlikely to make a comeback: As recently as 2013, local scientists concluded that pulverized shells had “no positive effect” on concrete strength.

Powdered oyster shell contains a small amount of nitrogen, so some is sold as fertilizer. Because it’s also rich in calcium and manganese, powdered shell is added to animal feeds, especially those for poultry. Some oyster shells are turned into decorations or handicrafts.

Yet a considerable surplus remains, as is obvious to anyone who visits an oyster-cultivating community like Wanggong (王功) in Changhua County or Baishueihu (白水湖) in Chiayi County. In those places, and a dozen others, oyster-shell dumps occupy vacant plots of land.

Cooperation between two state-run entities, Taiwan Sugar Corp (TSC) and the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI), led to the construction in 2018-2019 of a TSC-owned facility in Tainan’s Yongkang District (永康). It has the capacity to crush up to 50,000 tonnes of oyster shells annually, then calcinate (treat at high temperature but with a limited amount of oxygen) the fragments. For reasons of energy efficiency, temperatures inside the furnace don’t exceed 300 degrees Celsius.

Each year, around 40,000 tonnes of calcium carbonate are extracted from calcinated shells. This chemical compound is sold to pharmaceutical companies (including a unit of TSC) which use it in the manufacture of calcium supplements, antacid tablets and excipients (the non-active ingredient in pills).

TSC isn’t the only enterprise to convert discarded oyster shells into something that has commercial value. Changhua County-based Ecomax Textile Co makes and markets oyster-shell fiber which can be used in the manufacturing of fabric. The process begins with the drying of collected shells, which are then pulverized, formed into pellets, melted and spun.

The company also makes yarn out of the carbonized remnants of rice husks that were burned in biomass power plants.

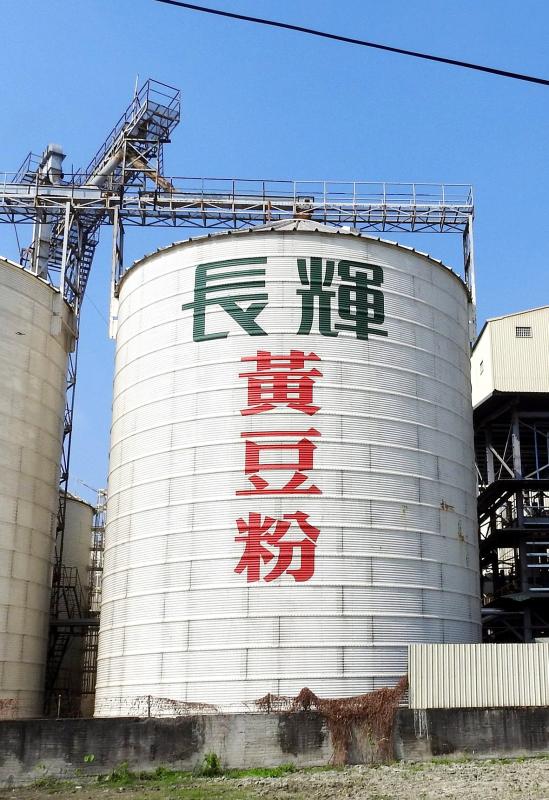

SOYBEAN PULP

Soy has been grown in Taiwan since well before the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule, but the ubiquity of soy foods is a postwar phenomenon that was made possible by imports from the US.

In the 1960s and 1970s, demand for soy came overwhelmingly from pig and poultry farmers. They fed their herds and flocks with soybean meal, a useful protein supplement made by crushing yellow soybeans, extracting the oil, then drying and toasting the pulp.

For a long time, meal for animals was the key product. Until Taiwanese consumers realized it worked well as an inexpensive cooking oil, food-processing companies regarded soybean oil as a low-value by-product.

Taiwan imports more than two million tonnes of soy per year, but demand for the pulp that’s left over once beans have been processed to make soymilk or oil has declined. Fear of African swine fever has caused many pig farmers to reject soybean dregs. (Last year, the same concern prompted the authorities to impose a temporary ban on feeding kitchen waste to hogs.)

What’s more, in Taiwan there has never been much call for a human food derived from soybean dregs. Some Westerners know it by its Japanese name, okara; Mandarin speakers call it doufu zha (豆腐渣).

This surplus has become a major problem for the companies that crush soybeans, as they need to dispose of approximately 400,000 tonnes of residual matter each year. Because these leftovers are prone to putrefaction (at room temperature, dregs begin to rot and smell bad within 72 hours), they can’t — unlike oyster shells — simply be dumped on unused land and forgotten about.

Recognizing this issue, ITRI has been working with members of the Taoyuan Tofu Industry Association to find other uses for soybean dregs. And they’ve hit on one that might turn out to be a winner: turning these unwanted leftovers into cat litter.

Most of the cat litter sold around the world is made of some kind of clay. Certain brands, however, are made from pine chips, wheat, walnut shells, corn cobs, sawdust or recycled paper.

According to an article published on ITRI’s Web site on June 15 last year, the development of low-cost technology that makes it possible to dehydrate and store dried soybean pulp was a breakthrough. Once the water content has been reduced to 10 percent, the material’s water-absorption properties make it highly suitable for use as cat litter.

According to ITRI, cat litter consisting of 50 percent to 80 percent processed bean dregs could one day appear on pet-shop shelves. With the average pet feline requiring at least 150kg of cat litter per year, such a product — if popular — would certainly get rid some of Taiwan’s surplus soybean pulp.

What’s more, ITRI scientists think, it may be possible to use these dehydrated soybean dregs as a base material in the production of pet biscuits. The pet-food market is huge: In 2019, Taiwanese pet owners reportedly spent more than NT$22 billion on edibles for their dogs and cats. However, persuading consumers to feed their animal companions on something that livestock farmers are known to reject might actually be more difficult than devising flavors that tempt pampered pets.

Steven Crook, the author or co-author of four books about Taiwan, has been following environmental issues since he arrived in the country in 1991. He drives a hybrid and carries his own chopsticks. The views expressed here are his own.

Exceptions to the rule are sometimes revealing. For a brief few years, there was an emerging ideological split between the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) that appeared to be pushing the DPP in a direction that would be considered more liberal, and the KMT more conservative. In the previous column, “The KMT-DPP’s bureaucrat-led developmental state” (Dec. 11, page 12), we examined how Taiwan’s democratic system developed, and how both the two main parties largely accepted a similar consensus on how Taiwan should be run domestically and did not split along the left-right lines more familiar in

As I finally slid into the warm embrace of the hot, clifftop pool, it was a serene moment of reflection. The sound of the river reflected off the cave walls, the white of our camping lights reflected off the dark, shimmering surface of the water, and I reflected on how fortunate I was to be here. After all, the beautiful walk through narrow canyons that had brought us here had been inaccessible for five years — and will be again soon. The day had started at the Huisun Forest Area (惠蓀林場), at the end of Nantou County Route 80, north and east

Specialty sandwiches loaded with the contents of an entire charcuterie board, overflowing with sauces, creams and all manner of creative add-ons, is perhaps one of the biggest global food trends of this year. From London to New York, lines form down the block for mortadella, burrata, pistachio and more stuffed between slices of fresh sourdough, rye or focaccia. To try the trend in Taipei, Munchies Mafia is for sure the spot — could this be the best sandwich in town? Carlos from Spain and Sergio from Mexico opened this spot just seven months ago. The two met working in the

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),