One of the most common — and most pointless — questions pollsters ask Taiwanese is whether they will fight against a Chinese invasion. Current polling, taken against the background of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, shows the number of people saying they would fight is rising.

For example, a recent poll by the International Strategic Study Society (台灣國際戰略學會) saw the count of those willing to fight against a Chinese invasion rising to 70 percent, against its poll number of 40.3 percent in December last year.

This is as one would expect. If the invasion of Ukraine ends and something like peace takes hold again, these numbers might well fall as the memory of Ukraine’s incredible bravery recedes.

Photo: Chen Feng-li, Liberty Times

Pollmongering on this issue is complicated by the simple fact that the international media loves to report that Taiwanese won’t fight, skewing perceptions. A widely-shared 2011 AP piece reported that Taiwanese youth were losing their appetite for fighting China, citing a Commonwealth Magazine poll of teenagers 12-17 (!) that did not even mention China. Pieces showing that Taiwanese youth don’t want to fight, with quotes from young people that military service is a waste of their time, appear regularly in the foreign media.

Fortunately, the Taiwanese response to Ukraine is starting to move media workers off this longtime trope. Perhaps someday those in the media might be able to look at China and see, not a nation-state, but an endless parade of Ukraines whose cultures are slowly being destroyed by the Chinese Communist Party’s imperial constructs of “Chineseness,” just as Putin claims Ukrainians are “Russians.”

The international media sometimes correctly contextualizes Taiwanese attitudes toward the military by referring to the widely hated Martial Law era military service. However, foreign media workers almost never contextualize potential Taiwanese resistance by locating it in the island’s long history of revolts and rebellions, settler violence and indigenous resistance.

Photo courtesy of ARS Film Productions

Because Taiwanese do not openly and self-consciously see themselves as occupiers of what was once a frontier state, visitors here are never treated to the kind of tourist experience that is normal in, say, the American West. Nor is the frontier experience an obvious part of Taiwanese masculinity and socialization, unlike the cowboy mythology of Americans.

For example, while there are numerous fortifications and other infrastructure left from the Dutch, Manchu (Qing Dynasty) and Japanese colonization periods, few presentations forthrightly situate their relics as objects of colonial expansion and sites of indigenous resistance and settler violence. Hence, the violence that has colored Taiwanese history as a frontier state largely disappears from media narratives about Taiwan.

Travelers across North and South America, by contrast, experience centuries of European colonialism that is self-consciously presenting what mainstream society knows to be imperial and colonial conquest. Consider a site like Fort Michilimackinac in the state of Michigan, where there are re-enactments and presentations showing the fort’s role in the conquest of the region. There’s even a nifty YouTube video of a re-enactment of the Ojibwe attack on the fort in 1763 (they took and occupied it for a year).

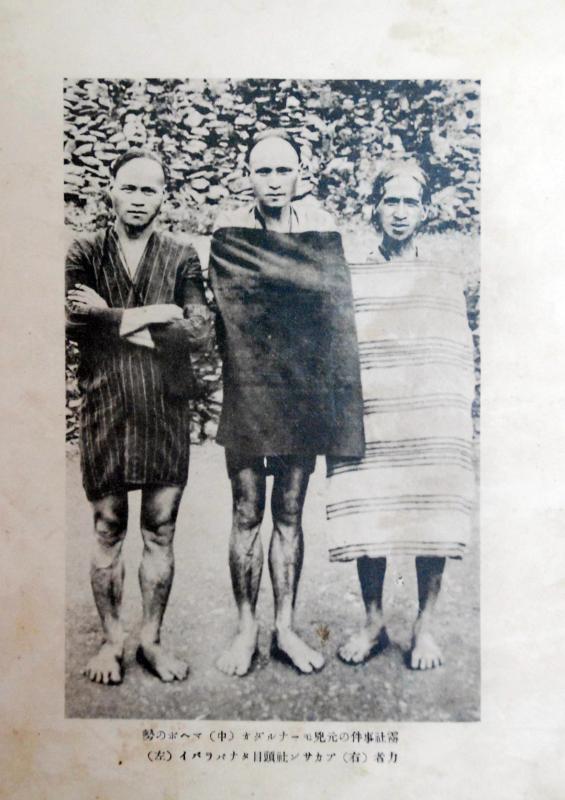

Photo courtesy of ARS Film Productions

Similarly, the second sentence on the US National Park service Web site for Fort Laramie in Wyoming observes that the fort “witnessed the entire sweeping saga of America’s western expansion and Indian resistance to encroachment on their territories.”

What kind of frontier society did Taiwan have? One that will be familiar to North and South Americans. John Shepard, in Murray Rubenstein’s Taiwan: A New History, described it thusly: “The prohibition on the immigration of wives and families led to the growth of a volatile, bachelor-dominated society in Taiwan that was prone to brawling and rebellion.”

In the 18th century alone, which opened with the massive revolt of Chu Yi-kuei (朱一貴) in 1721 that saw Qing officialdom almost swept off the island, and closed with the epic Lin Shuang-wen (林爽文) revolt of 1787-88, there were revolts roughly every eight years. By the 19th century, the interval had fallen to roughly every third year, according to a piece by Hsu Wen-hsiung (許文雄) on social organization during the Qing in Ronald Knapp’s China’s Island Frontier. Much Qing administrative energy was spent coping with the island’s rebelliousness.

Further, conflict between Hakkas and Hoklo settlers was endemic, with groups raiding each other’s temples and stockpiling weapons up to and including cannon. Different Hoklo groups also fought each other. Even today, though many famous temples were involved, doubling as fortresses and military bases, it is difficult to find this interesting and exciting history on the English Web sites and presentations of major temples in Taiwan.

For example, Longshan Temple in Taipei’s Wanhua District (萬華), built in 1740, functioned as the military headquarters of conflicts between various local groups for nearly 150 years, yet that is not mentioned on either the Tourism Bureau or the temple’s own English Web sites. Surely the occasional visitor must wonder why the Guan Gong (關公), the god of war and martial arts, occupies a space in the rear hall.

The terrible record of the violent, unremitting resistance of Taiwan’s indigenous people to Han Chinese settlement and outside colonizers is finally coming to the public consciousness with the appearance of the 1930 Wushe Incident (霧社事件) and the 1867 Rover Incident (羅妹號事件) in film and on TV in recent years. The peoples of the plains and mountains were also famed for their revolts against the Manchus.

For all its violence, let us also recall that Taiwanese frontier society was also organized along the lines of mutual self-help, at least among the Han Chinese. Taiwan was famous for its sworn brotherhoods and bands of bravos, who fought with each other. It is less known that among the local settlers it was common for people on the road to lodge at individual homes on the way. Hsu observed that “As late as 1894, a Japanese visitor still saw very few hostels on the island because travelers generally could lodge with friends.”

This tradition of mutual support, especially in times of trouble, should give any invader pause. Remember how the young flooded the south to help after the horrors of Typhoon Morakot in 2009? They will also flock to help if Taiwan is attacked.

The Japanese period was no different. Both Han Taiwanese and aboriginal revolts, along with other forms of organized social resistance to the colonizer, were common. When the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) arrived, they were greeted by all sorts of resistance, culminating in the 228 Incident.

Indeed, it might be more profitable to view the current era in Taiwan as a mere interlude between periods of fierce resistance, a little bubble of apparent, transient peace.

For the government, revisiting this deeper history beyond the Martial Law period might help build local identities and reinforce the will to resist. Imagine how much interest and conversation about the island’s history a re-enactment of the Chu Yi-kuei rebellion or other major revolt would engender (along with tourism dollars!). Imagine if the government in its communication with the outside consciously re-situated Taiwan and its peoples as longtime resisters against outside colonizers.

In the next few months the media is going to be filled with much commentary on what Taiwan can learn from Putin’s invasion. Taiwanese, looking at Ukraine, will learn many things, of course.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky teaches us that resistance is both possible and necessary, but also that it should be proudly situated deep in Taiwan’s long history of resistance.

Slava Ukraini!

Notes from Central Taiwan is a column written by long-term resident Michael Turton, who provides incisive commentary informed by three decades of living in and writing about his adoptive country. The views expressed here are his own.

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai

Following the rollercoaster ride of 2025, next year is already shaping up to be dramatic. The ongoing constitutional crises and the nine-in-one local elections are already dominating the landscape. The constitutional crises are the ones to lose sleep over. Though much business is still being conducted, crucial items such as next year’s budget, civil servant pensions and the proposed eight-year NT$1.25 trillion (approx US$40 billion) special defense budget are still being contested. There are, however, two glimmers of hope. One is that the legally contested move by five of the eight grand justices on the Constitutional Court’s ad hoc move

Stepping off the busy through-road at Yongan Market Station, lights flashing, horns honking, I turn down a small side street and into the warm embrace of my favorite hole-in-the-wall gem, the Hoi An Banh Mi shop (越南會安麵包), red flags and yellow lanterns waving outside. “Little sister, we were wondering where you’ve been, we haven’t seen you in ages!” the owners call out with a smile. It’s been seven days. The restaurant is run by Huang Jin-chuan (黃錦泉), who is married to a local, and her little sister Eva, who helps out on weekends, having also moved to New Taipei