A week after bone spurs robbed Chiao Chiao (巧巧) of the use of her hind legs, her owner’s friend recommended acupuncture therapy.

“I was like, can dogs even get acupuncture?” Choong Chee-wai (鍾志偉) says. “I had no clue. But after the first electro-acupuncture session, she stood up again.”

Several sessions later and the 15-year-old dachshund has regained about 80 percent mobility. Chiao Chiao also suffers from an incurable trigeminal nerve tumor, and Choong says treatment has alleviated the discomfort it causes.

Photo courtesy of Life Care Animal Hospital

Due to changing attitudes on pet ownership and increased media exposure in recent years, there are growing numbers of vet clinics in Taiwan who offer pet acupuncture services for animals who suffer from joint discomfort, spinal problems and other chronic issues.

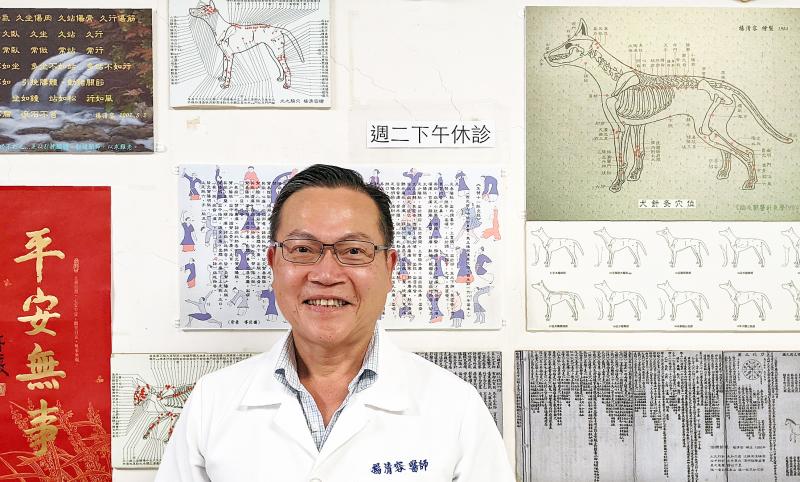

Chiao Chiao’s veterinarian, Yang Ching-jung (楊清容), however, says the practice has existed in Taiwan for decades.

“It’s just that more people know about it now,” Yang says. “I think it’s because of the media.”

Photo courtesy of Life Care Animal Hospital

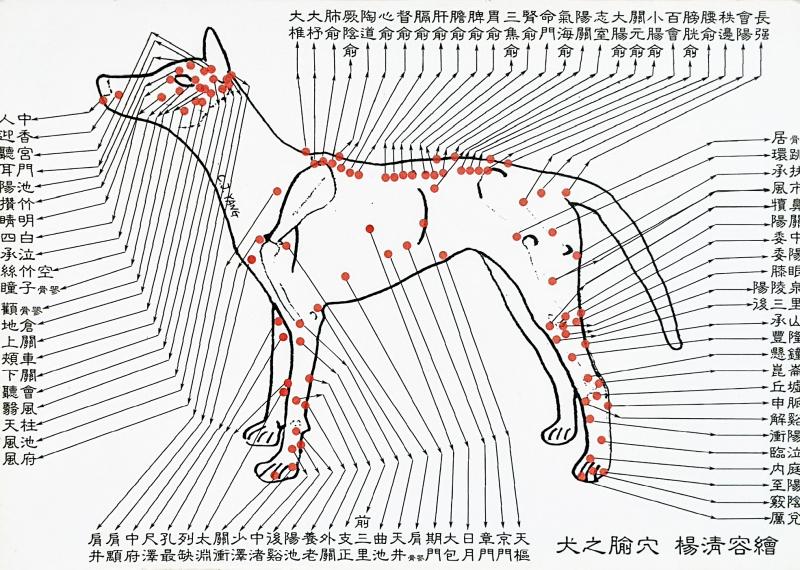

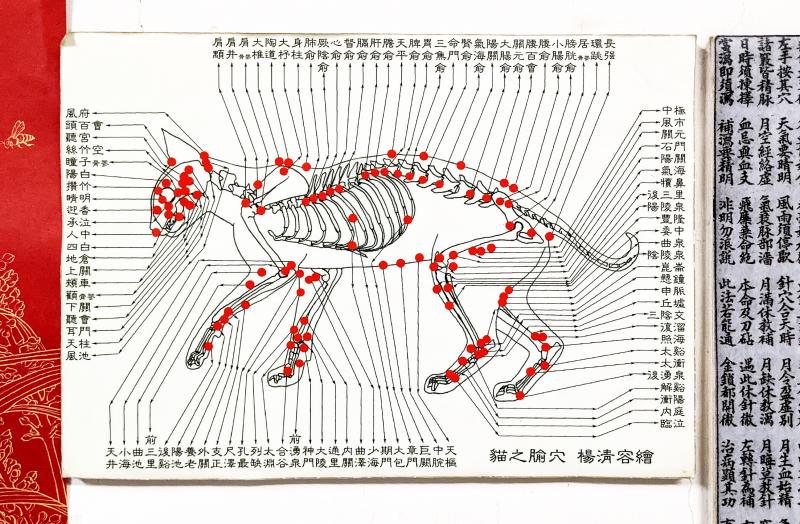

Yang started experimenting with it in 1978, and in 1984 he and three fellow veterinarians co-published Taiwan’s first comprehensive handbook on clinical veterinary acupuncture.

Yang painstakingly drew all the detailed diagrams in the book, which include not just cats and dogs but goats, horses and pigs. He also prescribes traditional herbal medicine to the animals.

Liaw Bor-sung (廖柏松) is among the new crop of acupuncture-practicing vets, receiving his certification from the US-based Chi Institute in 2018. He combines acupuncture and electro-acupuncture techniques with the innovative MLS (multiwave locked system therapy) system, although he prefers using needles because they can be applied to more pressure points.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“For acupuncturists, the feeling of the hands on the needles is very important,” Liaw says.

ACUPUNCTURE PIONEER

Yang’s book states that veterinary acupuncture has existed in China for thousands of years, dating as far back as the Western Zhou Dynasty (1045BC to 771BC), where records show physicians treating horses by sticking needles in their necks. The practice was mostly for working animals such as oxen, horses and camels.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Acupuncture and other traditional Chinese cures faded with the advent of Western medicine in the late 19th century, but they started gaining attention in the West during the 1970s. The US enacted the Traditional Chinese Medicine act in 1973 to regulate practitioners, and a year later, a group of American veterinarians started the International Veterinary Acupuncture Society.

Yang had been interested in acupuncture and traditional medicine since his days as a student at National Taiwan University’s School of Veterinary Medicine, but the school’s teachings were entirely Western with no resources for those interested in acupuncture. Yang tried to obtain a Chinese medicine doctor license, but after failing the exams, he became a veterinary surgeon.

He was fortunate to have a group of colleagues, such as Lin Jen-shou (林仁壽), who also shared his interest. Using ancient Chinese texts, modern technology and their bare hands, they managed to map out the pressure points of dogs, cats and other more common pets.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

After decades of experience and encouraging results, Yang and Lin in 2009 published a significantly expanded, four-volume edition of the original book to great fanfare. Today, Yang doesn’t perform much surgery anymore due to his age. Almost half of his cases now involve acupuncture. After Chiao Chiao leaves, an elderly woman comes in with her Maltese, who also lost his ability to walk months ago and has since recovered significantly.

“I really like doing [acupuncture],” Yang says. “This is more than just an interest. It’s a life-long endeavor.”

BECOMING A TREND

Photo courtesy of Life Care Animal Hospital

Liaw says he became interested in veterinary acupuncture when he realized the limitations of Western practices.

“For some older animals, it’s simply not suitable for them to undergo surgery or take too much medicine,” Liaw says. “I started looking for other ways to help them. I won’t say that acupuncture can replace surgery, but it at least gives them a better quality of life.”

Finding it too difficult and time-consuming to learn the traditional way, Liaw went through the Chi Institute’s online certification program like many of his contemporaries.

Photo courtesy of Life Care Animal Hospital

Liaw says the school uses the Western system of labeling each pressure point by category and position, making it much easier to memorize them. He sees the value in knowing the Chinese names of the pressure points as well: “If you learn the meanings behind the names, you’ll have a better idea how to use them.”

Like Yang, Liaw has also seen his share of paralyzed dogs and cats start walking again through acupuncture.

But not all animals are able to sit still or relax enough for the needles to stay put (cats are generally jumpier than dogs), so Liaw purchased the laser machine, which functions in a similar way without puncturing the skin.

Photo courtesy of Life Care Animal Hospital

“If the owner can afford it, I suggest they undergo both acupuncture and laser treatment,” Liaw says. “But if they can just choose one, I recommend acupuncture.”

Most of Liaw’s clients hear about his clinic by word of mouth, or through Instagram and other social media. He agrees that the demand is growing.

“Some people bring their pets here after seeing their neighbor’s paralyzed dog suddenly walking again,” he says. “There’s more and more people learning veterinary acupuncture in Taiwan, and the service is becoming more accessible.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Still, it’s not a miracle cure.

“I try to do what I can, but depending on the pet’s condition, sometimes I have to tell the owners that it’s not worth it. These are all choices that people have to make. There are also animals who progress slowly through acupuncture, and the owners get tired of waiting and bring them to surgery instead.”

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she