To plan a return to Taiwan in early October, I began calling the Central Epidemic Command Center’s (CECC) COVID hotline in late July to arrange quarantine accommodations. Taiwan requires all incoming travelers to stay in quarantine hotels paid at their own expense.

Due to a chronic illness, I have an almost absurd number of dietary restrictions and am highly sensitive to mold. Eating a typical Taiwanese lunchbox (or any sugars or starches) or staying in a moldy room can make me sick, and this could be compounded horribly were I trapped in a bad situation for the required 14-day quarantine period.

Though my health situation is somewhat unique, I am among tens of thousands of residents in Taiwan who have travelled overseas during the pandemic, and then have had to face the dilemma of if, how and when to return to the island.

Photo: AP

Taiwan’s quarantine hotel system was put into place in late June. Currently the average cost of a room is NT$2,750 per night, meaning a 15-night stay will cost NT$41,215, or almost US$1,500. Since all travelers must stay in individual rooms — couples are not allowed to stay together — costs can multiply dramatically for families. And while there are possibilities of medical exemptions for dual occupancy hotel rooms or home quarantine, there is no application process. One can only call the CDC COVID hotline, where call center workers refuse to give their names and inform you of their “final” decisions.

IMPACT ON FOREIGNERS

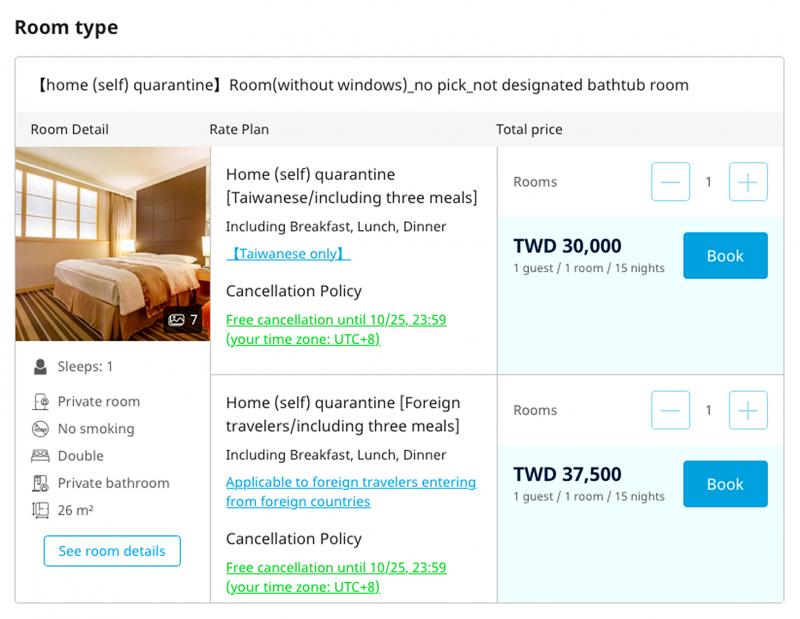

The hotel quarantine system is also biased against foreign residents. Government quarantine subsidies of NT$1,000 per day are reserved for Taiwanese citizens only and some hotels charge a “foreigner price” which can be more than 20 percent higher than the Taiwanese price.

Photo: AP

To take Taipei’s Relite Hotel as an example — it is one of several hotels offering a “Taiwanese only” price on their Web sites — a full quarantine stay of 15 nights is NT$34,500 for a Taiwanese citizen, who may then apply for a NT$15,000 government quarantine subsidy, paying a net cost of NT$19,500 for the stay. For a foreigner — and keep in mind only resident foreigners are allowed to enter the country, no tourists — the price is NT$42,000, more than double the net cost to a Taiwanese.

The number of both Taiwanese and foreign nationals staying away from Taiwan is growing, reversing last year’s trend of Taiwanese flocking to the nation as a safe harbor. According to figures on the National Immigration Agency’s Web site, while Taiwan last year saw a net gain of 270,000 Taiwanese nationals entering the country, this year has so far witnessed an outflow, with 93,000 more departures than arrivals of citizens and other permanent residents through the end of August.

Though this volume of travelers may seem slight, in COVID times it is significant. Since the start of the pandemic, the number of travelers passing across Taiwan’s borders has dropped almost 50 fold, from 4.8 million per month in 2019 to 95,000 per month since March last year.

Photo: David Frazier

The exit trend has been even more pronounced among Taiwan’s 770,000 strong foreign population, which has seen a net balance of 46,000 foreigners leaving Taiwan since the pandemic was declared in March last year, or around 5 percent. The cost of hotel quarantine is a major factor.

WAITING IT OUT

Once a world leader in dealing with the pandemic, Taiwan has become less of a “place to be.” According to Bloomberg’s COVID Resilience Ranking, which ranks the best countries to live in based on vaccination rates, severity of lockdowns and ease of travel, Taiwan has fallen from the top 5 in the first part of the pandemic to its latest October ranking of number 42 out of 53 nations in the survey.

Photo: Bloomberg

“I came back to the US for the death of a relative, and I have to delay going back to Taiwan, because I don’t want to spend a couple thousand dollars for hotel, when I already spent three grand for my flights, on top of the fact that I’m not really working,” said Jen Wen, a teacher and Taiwan-US dual citizen.

“One of the big problems for foreigners is that they all have relatives overseas, where with Taiwanese, that’s not necessarily the case,” she added.

One of the biggest travel deficits has been to and from Western countries, with more than three times as many departures for North America and Europe as compared to arrivals since the start of the pandemic –– 157,000 departures versus 51,000 arrivals recorded at Taiwan’s airports from March last year to September, according to the Taiwan Tourism Bureau.

In my own group of friends, I can count at least a dozen Taiwan residents of a decade or longer — including journalists, businesspeople, teachers, airlines workers, bankers and restaurateurs — currently waiting for quarantine restrictions to loosen before they return.

“The costs of returning are just ridiculous. If we could do home quarantine, I’d consider it, but with hotel quarantine how it is now, we’re just going to stay in the US and wait it out,” said an American trading company owner and Taiwan resident of almost three decades.

As travel opens up internationally and global vaccination rates rise, the question of when Taiwan can finally lower the drawbridge, even partially, is becoming more persistent. But the greatest pressure will likely coming from the approaching Chinese New Year, which begins from February next year and promises a surge of returning Taiwanese.

Most quarantine hotels for January were fully booked more than three months in advance, and the government seems unable to add enough capacity. So far, the CDC has “temporarily” reduced hotel quarantine from 14 to 10 days, and hotel quarantine may be cut to 7 days, at least from Dec. 14 to Feb. 14 (with an additional 7 days home quarantine).

HEALTH EXEMPTIONS

As for my own predicament, what became clear after dozens of phone calls to Taiwan’s health authorities made over a two-month period is that they have no procedure to deal with special health concerns in quarantine or submit a letter from a doctor.

When asking staff at Taiwan’s various COVID hotlines how I could submit medical proof of my condition, or how I could be assured of a non-moldy room and 2,000 calories a day that my body could tolerate –– or a room where I could cook my own meals –– I was told at various times, “Maybe you should just stay in your home country longer.” Or: “Try hotels in another part of Taiwan.” Or, “There is no way to make any sort of application. We deal with everything through this hotline.” Or, “Please check our Web site.”

At the same time, I also tried contacting quarantine hotels directly. Several refused me outright based on my dietary requirements. One hotel offered to give me a gas burner, which I would presumably place on the floor and cook over an open flame between the bed and the curtains. It was an obvious fire hazard, a threat to both myself and every other guest in the hotel.

Most hotels told me they outsource preparation of guest meals — usually a Taiwanese lunchbox of meat, vegetables and rice — to outside food services, so they had no way to accommodate special diets. Still, they informed me that rooms get booked very early and I should place a deposit quickly.

After six weeks of frustration and about two weeks before my planned return, I finally had a breakthrough in calling my municipal health bureau. (I live in Yilan County.) After two weeks of fraught phone calls and refusal of service from several hotels, I had a brainstorm: What does Taiwan’s bureaucracy react to?

Complaints.

So I called the Yilan general citizens complaints hotline and filed a complaint against the Yilan County Public Health Bureau. After that they talked to me, took a letter from my US doctor, inspected my apartment with my landlord and prepared an application to the central government’s CDC. The CDC’s letter for approval came one day before I boarded my flight for Taiwan.

Since my return, numerous foreign friends have asked me how I “hacked the system.” The problem is that one should not have to hack the system. A process is needed for medical exemptions, and the hotel quarantine system should not be biased against foreign residents. Within Taiwan’s larger plan of eventual re-opening, these are two obvious steps.

This is the year that the demographic crisis will begin to impact people’s lives. This will create pressures on treatment and hiring of foreigners. Regardless of whatever technological breakthroughs happen, the real value will come from digesting and productively applying existing technologies in new and creative ways. INTRODUCING BASIC SERVICES BREAKDOWNS At some point soon, we will begin to witness a breakdown in basic services. Initially, it will be limited and sporadic, but the frequency and newsworthiness of the incidents will only continue to accelerate dramatically in the coming years. Here in central Taiwan, many basic services are severely understaffed, and

Jan. 5 to Jan. 11 Of the more than 3,000km of sugar railway that once criss-crossed central and southern Taiwan, just 16.1km remain in operation today. By the time Dafydd Fell began photographing the network in earnest in 1994, it was already well past its heyday. The system had been significantly cut back, leaving behind abandoned stations, rusting rolling stock and crumbling facilities. This reduction continued during the five years of his documentation, adding urgency to his task. As passenger services had already ceased by then, Fell had to wait for the sugarcane harvest season each year, which typically ran from

It is a soulful folk song, filled with feeling and history: A love-stricken young man tells God about his hopes and dreams of happiness. Generations of Uighurs, the Turkic ethnic minority in China’s Xinjiang region, have played it at parties and weddings. But today, if they download it, play it or share it online, they risk ending up in prison. Besh pede, a popular Uighur folk ballad, is among dozens of Uighur-language songs that have been deemed “problematic” by Xinjiang authorities, according to a recording of a meeting held by police and other local officials in the historic city of Kashgar in

It’s a good thing that 2025 is over. Yes, I fully expect we will look back on the year with nostalgia, once we have experienced this year and 2027. Traditionally at New Years much discourse is devoted to discussing what happened the previous year. Let’s have a look at what didn’t happen. Many bad things did not happen. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) did not attack Taiwan. We didn’t have a massive, destructive earthquake or drought. We didn’t have a major human pandemic. No widespread unemployment or other destructive social events. Nothing serious was done about Taiwan’s swelling birth rate catastrophe.