It’s been a long time since a book made me laugh out loud — and multiple times at that. Granted, I usually read humorless nonfiction titles, but this twisted, relentlessly satirical “Buddhist comedy” set between Boulder, Colorado and Taiwan hit the right spot with its brand of completely absurd yet somehow controlled chaos that, frighteningly, is not too far off from the bizarre reality we live in today. It helps that I’m familiar with both places, and the stereotypes ring mostly true.

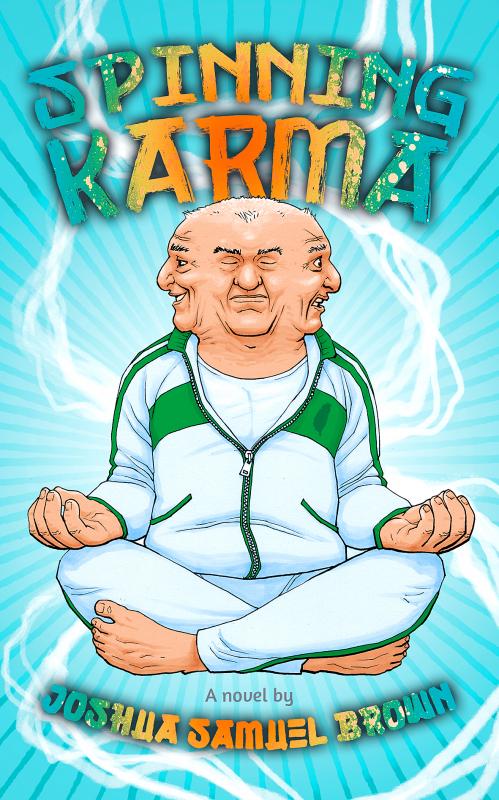

Set in a faux post-Trump world where tensions between China and the US are high, the tale follows Edward “Rinpoche” Schwartz, the tracksuit wearing, sleazy leader of a disgraced American pseudo-New Age-Buddhist cult whose half-hearted publicity stunt suddenly thrusts him into the center of an international propaganda war between the two nations.

Reality and fiction become increasingly blurred as nobody is interested in the truth, each side trying to control Schwartz’s narrative to manipulate public perception. One of the many hijinks includes a Chinese qigong master pulling a tractor trailer with his genitals on national television. Oh, and the cult is called “Mind of Pure Enlightenment” — or “MOPE” for short.

Joshua Samuel Brown’s prose is brisk, vivid and biting, making for a fast paced yet thoughtful read. It covers a lot of territory and pokes fun at a wide range of phenomena within its 240 pages, but the book can be devoured in one go without much problem. Nothing is as it seems as Brown hurls the reader through countless twists and turns, and the narrative flows and makes sense despite the madness that unfolds up until the very end.

Without spoiling the plot, Schwartz actually spends his time abroad not in China but in Taiwan, focusing much narrative attention to the plight of the nation that’s often a flashpoint in the clash between the two global powers. Schwartz immediately gets tangled in a series of misadventures in a caricatured version of Taiwan largely seen through the eyes of a Westerner, which fits the story’s premise anyway and doesn’t purport to be something it’s not. Brown has spent considerable time in Taiwan and his previous book, Formosa Moon, co-authored with Stephanie Huffman, is a love letter to the nation he considers his second home. A prolific travel writer for Lonely Planet and other publications, this is his first work of fiction.

It’s evident that Brown has a decent grasp of the nuances of Taiwanese and Chinese culture, as one needs to have a foundation first before getting creative. There are some glitches that may bother a native Mandarin speaker, but overall his observations are hilariously and stereotypically accurate. Those who have lived in Taiwan will definitely chuckle at items like the “Ministry of Formalities” situated across the street from the Presidential Office, with a minister that spends nine months of the year abroad promoting Taiwan as a country while his lackeys shirk responsibility and spend public funds at spas that offer sexual services.

One can argue that many of the locals feel like cliches — the burly gangster with a soft heart, the ditzy spa masseuse, the woman married to a foreign English teacher. In any event, Schwartz isn’t there to absorb local culture, but to further his own goals.

It’s not just Taiwanese; everyone is more or less a parody in the book, starting from Schwartz’s Hispanic teenage followers who pepper every sentence with ese to the right-wing, gun-toting, bible-thumping congresswoman Hoffman and the hapless, Harvard-educated Chinese diplomatic agent Guo. Nobody is safe under Brown’s pen, including the ethics-lacking, click-thirsty reporters from both “American Public Radio” and “Badger News Network.” It’s not hard to figure out who these outlets are in real life.

This ambiguity is the most intriguing aspect of the book. The humor is sometimes so sardonic it’s hard to tell which parts are serious and which aren’t, but then it’s also easy to just roll with the fun. And as improbable as the events are, Brown also keeps the narrative from going over the top, keeping the reader surprisingly grounded.

Rinpoche Schwartz is the embodiment of this notion. He’s a deeply flawed character that we’re taught to despise in society, the type that constantly breaks the principles he profits from and bristles at the fact that a Tibetan monk can take over his Buddhism class while he goes by an honorific title used by Tibetan spiritual teachers. Despite his selfish behavior, he’s also aware that he’s mostly a fraudster who never wanted this role, but he also seems sincere enough in his teachings and spiritual practice, something made more murky when Brown throws in arcane Buddhist terms to suggest that Schwartz does know a thing or two.

Though Brown has grasped the general use of language in Taiwan, including the mixed use of Mandarin and Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese), there are some parts that are a bit off.

For example, it is very rare in Taiwan to say nali, nali in response to being thanked; it’s used to show humility when being praised. Some of the Chinese names are problematic — “Ru-nei” and “Da-nei” are highly implausible names in Mandarin, and even if Brown wanted them to sound like Ronnie and Danny, it would be “Luo-ni” and “Dan-ni.” Yes, he does have American characters called Chip Chasen and Carl Cosby, but at least those are real English names.

That’s nitpicking though, and underneath the entertaining romp there’s a concerning message about the sorry states of modern media and both domestic and international politics. It’s worth picking up even if you don’t know much about Buddhism or Taiwan.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she