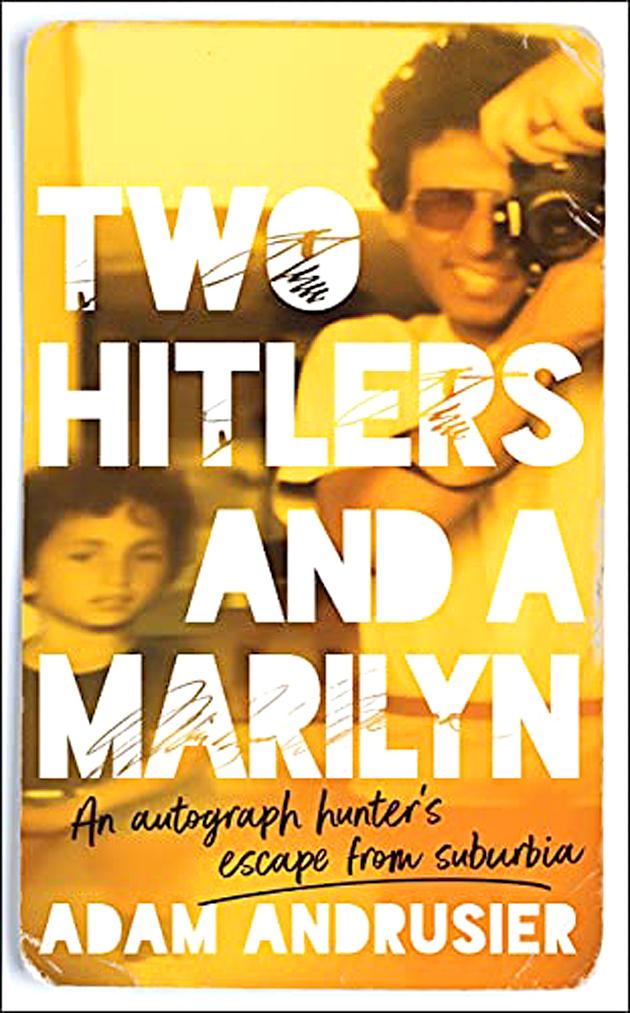

The obsessiveness — the downright creepiness — of the collector is amusingly skewered in this memoir of rueful self-absorption. In the 1980s, long before selfies, autographs were the accepted means of stealing a celebrity’s soul and hunters seldom came more tenacious than young Adam Andrusier. A nice Jewish boy from Pinner, he first catches the scent of his habit on learning that his best friend’s neighbor is actor Ronnie Barker. Knocking at his door, they are answered by a lady who turns them away, though Adam spots the man himself in the hallway before the door closes: “He didn’t look famous at all.”

He has better luck when, on holiday in France, he spots Big Daddy in the hotel swimming pool; after careful stalking, he nabs his prey with paper and pen: who cares if the wrestler’s real name is Shirley Crabtree?

“I’d managed to puncture a hole between our universe and the parallel one where all the celebrities lived.”

From that moment, there’s no stopping him. In a way he was born to it. His father, Adrian, sold life insurance, but his passions were collecting books on the Holocaust and rare postcards of lost synagogues. He takes Adam to his first ever dealers’ fair, where a jaded old pro tells the boy that most of his present collection is “secretarial,” ie, not signed by the stars themselves. A hard lesson for the fledgling collector, but he learns from it and by the time he’s trading autographs professionally he has an eye for spotting fakes (“if the writing was too slow, if it looked flat or lifeless”).

The strange and elusive world of collecting is the engine of Two Hitlers and a Marilyn, but its mystery plot is going on elsewhere and revolves around the figure of the author’s father. A strong personality but a weak character, Adrian lives for Thursday nights with his cronies, the highlight of his year a six-day festival of Jewish folk dancing at Hatfield Polytechnic — and a nightmare of embarrassment for his long-suffering wife and children.

By degrees, the seeming innocence of his gregarious other life curdles into something furtive and suspect. There’s also the puzzle of his Holocaust obsession, given it was his wife’s grandparents who perished in the camps, while Adrian’s family had been safe in England during the war, “avoiding conscription.” Gradually, the antagonism between father and son becomes unignorable, a conflict based not on faith — Adrian is no devout observer and Adam no Edmund Gosse — but on the marshier ground of truthfulness. The discovery of an incriminating letter in his father’s briefcase smoulders away for pages.

Of course Adam is smart enough to realize he is, in part, a chip off the old block. Just as his father is ruled by obsession — always intruding with his camera, always ready with an old joke — Adam pursues his career in autographs with a single-minded intensity, traveling to fairs around the world, glued to his dealers’ lists and catalogs.

The suspicion that he might have “a bit missing” occasionally surfaces, like the moment he hears that Salman Rushdie, then under the fatwa, is to do a signing at Waterstones: “It crossed my mind that a signed copy of The Satanic Verses might be worth some real money, especially if someone managed to take Rushdie out.”

There’s compassion for you!

Almost from the corner of our eye we see his “normal” life going on. He not only has a girlfriend, but he turns out to be a pianist worthy of a place at King’s College, Cambridge. His love of jazz and its mavericks (Miles Davis, Bill Evans) prompts some of his best writing. But overshadowing even the happy times is a volatile temperament.

The thin partitions dividing talent from mania begin to wobble when he gives a public recital of Ravel’s Piano Concerto in the college chapel and all the dread and resentment brewing inside him burst out mid-performance: he stares at his hands “playing the piece, all by themselves. I wasn’t doing anything except observing. It was an astonishing sight.” A spectacular unRavel-ing follows.

The final reckoning with his father occurs in a chapter titled, with no small irony, “Hitler.” Having circled a signed volume of Mein Kampf for sale, Adam at last breaks the taboo and buys it, recognizing the purchase partly as an act of aggression. He knows his father — and everyone else — will be appalled, the idea of his owning it horrible yet “electrifying.” It takes a conversation with his therapist to make him realize what’s going on. As his girlfriend puts it, more succinctly: “If you want to upset your dad, why don’t you just buy a German car?”

I wonder if the book is settling another score. On its cover, Zadie Smith provides a puff (“a comic and poignant memoir”), which was perhaps exacted by the author as the price for her using his story in her 2002 novel The Autograph Man. Was his permission sought back then or did Smith simply do what most writers would and appropriate it? Either way, Adam Andrusier has put his own spin on this chronicle of filial dysfunction and compulsive collecting. I wonder if I can get my copy signed?

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

It was on his honeymoon in Kuala Lumpur, looking out of his hotel window at the silvery points of the world’s tallest twin skyscrapers, that Frank decided it was time to become taller. He had recently confessed to his new wife how much his height had bothered him since he was a teenager. As a man dedicated to self-improvement, Frank wanted to take action. He picked up the phone, called a clinic in Turkey that specializes in leg lengthening surgery — and made a booking. “I had a lot of second thoughts — at the end of the day, someone’s going

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Standing on top of a small mountain, Kim Seung-ho gazes out over an expanse of paddy fields glowing in their autumn gold, the ripening grains swaying gently in the wind. In the distance, North Korea stretches beyond the horizon. “It’s so peaceful,” says the director of the DMZ Ecology Research Institute. “Over there, it used to be an artillery range, but since they stopped firing, the nature has become so beautiful.” The land before him is the demilitarized zone, or DMZ, a strip of land that runs across the Korean peninsula, dividing North and South Korea roughly along the 38th parallel north. This