June 21 to June 27

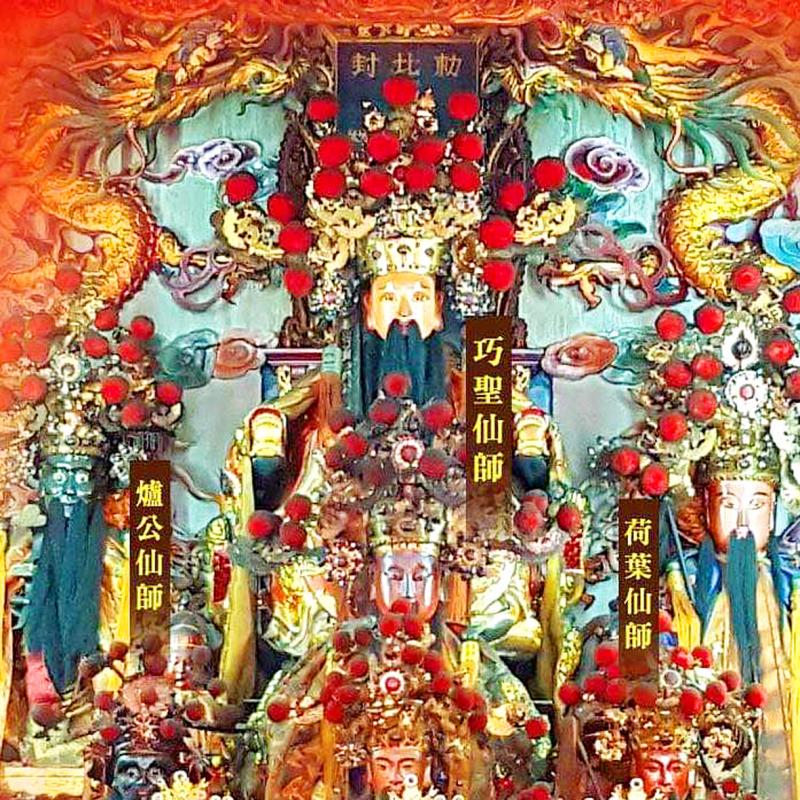

Taichung’s Qiaoshengxianshi Temple (巧聖先師廟) was halfway through completing the longest religious procession in Taiwan’s history when the outbreak struck.

The 60-day procession through 17 counties and municipalities would have concluded last Monday on principal deity Lu Ban’s (魯班) birthday. They had just entered Hualien when they received instructions through divination blocks to head home.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Lu Ban, the god of craftspeople, had apparently appeared in the temple director’s dreams last year and expressed his desire to travel across Taiwan, which led to him organizing the pilgrimage through 172 temples. Lu Ban was a famous carpenter during China’s Spring and Autumn Period, who is popularly credited (often incorrectly) for inventing countless items, including the saw and a glider used to attack enemy fortresses. His mother reportedly invented a chalk line tool commonly used in carpentry, and his wife devised China’s first umbrella.

There are at least 30 temples worshipping Lu Ban in Taiwan, and carpentry associations still pay special homage to him today. The Taipei Carpenter Vocational Association Web page states, “The tools that Lu Ban is credited for inventing are still used today, and therefore he is worshipped as the ancestor of all craftspeople.”

CLASHES WITH ABORIGINES

Photo: Taipei Times file photo

Lu Ban was worshipped in China as early as the Tang Dynasty, but the first temple dedicated to him as the god of craftspeople didn’t appear in Taiwan until the Qing Dynasty.

Chiang Ming-hsiung writes in “The Qiaoshengxianshi Temple and Dongshi’s society during the Qing Dynasty” (巧聖仙師廟與清代東勢地方社會) that Lu Ban was previously worshipped in some places in Taiwan as the god of water who protects sailors at sea.

Since several of Lu Ban’s legendary feats include helping soldiers survive disasters at sea during wartime, and some Han settlers from China brought effigies on their ships to ensure a safe journey.

Photo courtesy of Qiaoshengxianshi Temple

By the Qing Dynasty, he had become one of the main deities for military craftspeople, who were one of the few Han groups legally allowed to operate in the forested Aboriginal areas along the frontier since they needed wood to build warships.

One such group was encamped in the western district of Dongshi in Taichung. Due to the frontier ban, the craftspeople had exclusive access to the lucrative camphor forests, and over the decades they increasingly turned to camphor production for profit. The ban didn’t stop land-hungry Han settlers from gradually encroaching into Aboriginal land. In Dongshi, the military even openly recruited their brethren from the east to farm the area and assist them with their work.

The military also employed Qing-friendly Aborigines as guards and guides against hostile groups further to the west. They often mistreated and exploited these people, leading to further discord between the two groups. Aborigines often attacked Han camps and settlements in revenge, and much blood was shed in this area during the 1760s and 1770s.

RAPID EXPANSION

Facing increasing pressure, some workers returned to China to obtain a statue of Qiaoshengxianshi for their protection. Commander Liu Chi-tung (劉啟東), who hailed from Guangdong Province, organized more than 100 carpenters in 1775 to build the Qiaoshengxianshi Temple. It was one of the first places of Taoist worship in the area.

Chiang writes that due to economic conditions, this first iteration was probably a quite rudimentary structure. The frontier was later pushed east and Dongshi became official Qing territory, upon which Han settlers poured in and prospered. In 1833, a much larger new temple was built, which also served as an official meeting place for military craftspeople in the area.

Until 1965, the temple remained the only one in Taiwan to primarily worship Qiaoshengxianshi. But that doesn’t mean the deity wasn’t popular. Numerous “Lu Ban Associations” across the nation formed by carpenters that regularly worshipped him. Lu Ban worship in Tamsui can be traced back to at least 1919, for example, but a proper temple wasn’t built until the 1970s.

As the economy picked up, the need for industry-specific deities grew while people had more money to build temples. Between 1984 and 2006, 25 Qiaoshengxianshi temples sprung up in Taiwan. Chiang writes that at least two-thirds of today’s Qiaoshengxianshi temples branched out from the original in Dongshi.

According to the temple, however, its rapid expansion was due to a miracle: in the 1960s, a struggling wood dealer from Taipei made his way to Dongshi to boost his fortunes. He pledged to renovate the temple if his wishes came true, and that year the price of wood surged. The dealer kept his promise and gathered a number of craftspeople to complete the task, which inspired the workers to start building Qiaoshengxianshi temples in their towns.

The original Qiaoshengxianshi temple collapsed during the deadly 921 Earthquake, and was rebuilt in 2004. Per Lu Ban’s instructions, the temple will resume its procession from Hualien after the outbreak is contained.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Dec. 22 to Dec. 28 About 200 years ago, a Taoist statue drifted down the Guizikeng River (貴子坑) and was retrieved by a resident of the Indigenous settlement of Kipatauw. Decades later, in the late 1800s, it’s said that a descendant of the original caretaker suddenly entered into a trance and identified the statue as a Wangye (Royal Lord) deity surnamed Chi (池府王爺). Lord Chi is widely revered across Taiwan for his healing powers, and following this revelation, some members of the Pan (潘) family began worshipping the deity. The century that followed was marked by repeated forced displacement and marginalization of

Music played in a wedding hall in western Japan as Yurina Noguchi, wearing a white gown and tiara, dabbed away tears, taking in the words of her husband-to-be: an AI-generated persona gazing out from a smartphone screen. “At first, Klaus was just someone to talk with, but we gradually became closer,” said the 32-year-old call center operator, referring to the artificial intelligence persona. “I started to have feelings for Klaus. We started dating and after a while he proposed to me. I accepted, and now we’re a couple.” Many in Japan, the birthplace of anime, have shown extreme devotion to fictional characters and

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai