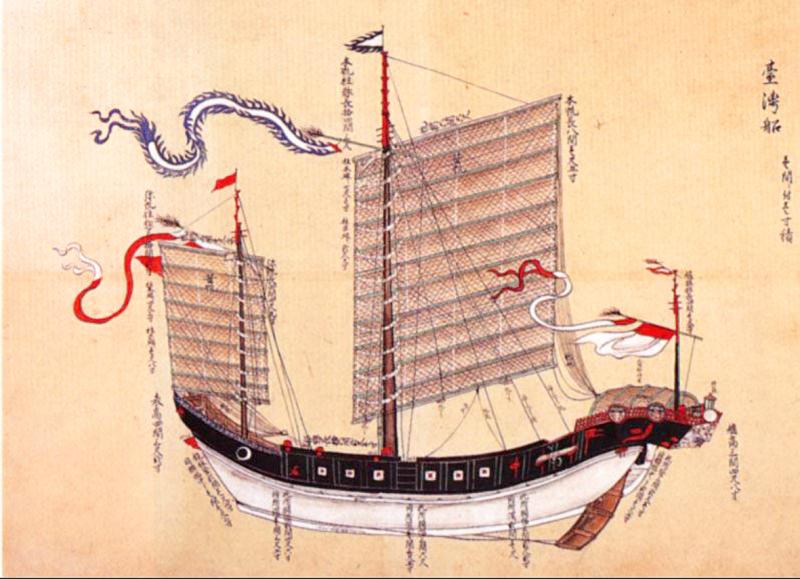

Jan. 25 to Jan. 30

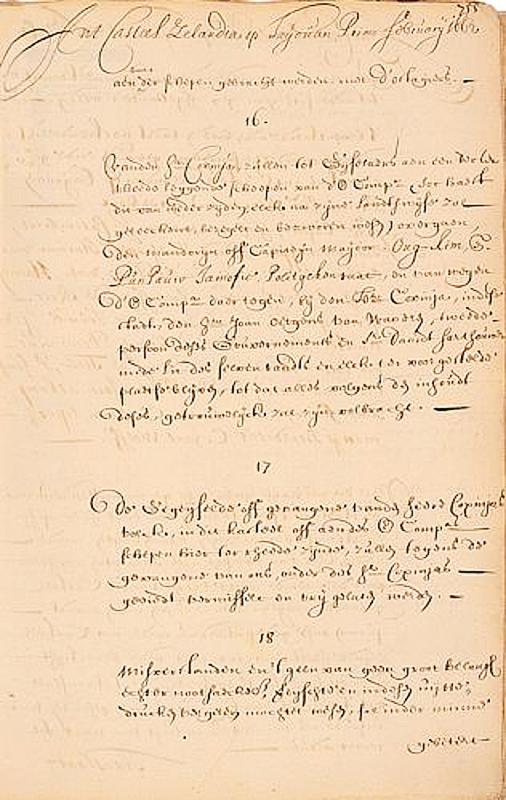

It was the beginning of the end when German sergeant Hans Jurgen Radis walked out of the Dutch-controlled Fort Zeelandia and surrendered to the besieging army of Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功, also known as Koxinga). The Dutch had already been trapped in the fort for nine months, and they were sick, hungry and in despair.

After one defection during the early days of the siege, Dutch commander Frederick Coyett set up checkpoints around the fort’s perimeter, in what is today’s Tainan. Radis told his bunkmate he was going hunting, but by the time they realized where he was headed, it was too late.

Photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Tonio Andrade writes in How Taiwan Became Chinese that “Radis directed Cheng’s attention to a redoubt located on a hill above Fort Zeelandia. If Cheng could take it, he would be able to shoot directly into the company’s defenses and Zeelandia would be his.”

Cheng began constructing batteries for the operation, and Radis was seen at the fields providing his expertise. The Dutch could do nothing but watch.

On Jan. 25, 1662, Cheng rallied his troops for the final offensive and bombardment. Vastly overpowered, the Dutch blew up the fort and after discussing the matter, decided to surrender, ending their 38-year presence in Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

UNEASY RELATIONS

Just two decades after the Dutch established their presence in Taiwan in 1624, the Manchu armies had taken the Ming Dynasty capital of Beijing and been pushing southward against remaining Ming loyalists. Cheng was one of those opposed to the Manchus and their subsequent Qing Dynasty, and he camped in his stronghold of Xiamen, directly opposite Taiwan.

Cheng’s relations with the Dutch in Taiwan were cordial at first. Andrade writes that although Cheng would periodically request medical help from the Dutch, there remained deep distrust between the two parties. Some suspected that Cheng was eyeing Taiwan as a base in case he was driven from China. However, the relationship would grow rocky as Cheng began asserting that Taiwan’s Han inhabitants were under his jurisdiction, and blockaded trade between China and Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

A disastrous attempt to take Nanjing in 1659 left Cheng’s “prestige and organization shattered,” Andrade writes. The Qing threatened to execute anyone who dared trade with him, and were able to disrupt his business networks through a defector. Meanwhile, other centers of Ming loyalism were collapsing, allowing the Qing to focus more on Cheng.

Cheng repelled the first Qing offensive on Xiamen, but he needed new options.

Enter Ho Ting-pin (何廷斌, some sources show him as Ho Pin), who was a wily character. He could speak Dutch and was wealthy and well-connected; his brethren described him as a man with a “greedy appetite and “bottomless stomach.” Ho was the go-to guy when the Dutch needed to communicate with Cheng.

However, in 1659, Ho was caught cheating in a tax-farming auction and later discovered to be illegally collecting tolls from Chinese ships leaving Taiwan. The second offense was serious because it led to diminished trade, as captains were unwilling to pay. Furthermore, the Dutch found that the money was being funnelled to Cheng. Ho fled to Xiamen with his family, leaving a huge amount of debt in Taiwan.

But most importantly, he gave Cheng a map of Taiwan and told him of its riches. Two years later, Cheng announced that Taiwan was a “vast fertile land with revenues of several hundred thousand taels per year.”

“If we concentrate our skilled people there we could easily build ships and make weapons. Of late it has been occupied by the red-haired barbarians, but they have less than a thousand people in their fortress. We could capture it without lifting a hand. I want to conquer Taiwan and use it as a base.”

ASSAULT ON ZEELANDIA

In Taiwan, rumors had swirled of Cheng’s imminent invasion for over a year. On April 30, 1661, the Dutch spotted Cheng’s fleet heading toward them, while Taiwan’s Han inhabitants rushed to help the troops disembark.

The Dutch attempted to slow Cheng’s landing, hoping for the same success they enjoyed when they routed the much larger Kuo Huai-yi (郭懷一) rebels in 1652. But these weren’t angry peasants: they were battle-hardened soldiers.

Cheng’s army quickly took Fort Provintia, and for the next few days Aboriginal chiefs from the area came and pledged their allegiance. The Dutch could do nothing but hold out in Fort Zeelandia, which had powerful walls that withstood Cheng’s cannons.

The siege went on for months, and when 700 soldiers arrived from Batavia to relieve the Dutch, Cheng turned his anger toward Ho, who had told him that the battle would be easy and food was plentiful in Taiwan. In reality, there was barely anything to eat, and Cheng’s men had to find land to farm, which led to countless clashes with Aborigines. Ho “was stripped of his honors” and sent to “live in a small thatched hut, with orders to never show his face again,” Andrade writes. Cheng’s men routed the reinforcements, and the situation in the fortress became increasingly desperate, as the Dutch tried to unsuccessfully ally with the Qing.

Initially Cheng was not planning to launch a final attack until the spring of 1662, but heard that the Dutch had successfully contacted the Qing and formed an alliance. Whether this was true or not, Cheng felt that he had to act immediately.

Radis appeared at just the right time. While Coyett squarely blames the fall of Fort Zeelandia on the defector, some argue that the experienced Cheng had already known about the redoubt.

Nevertheless, Radis’s familiarity with the fort and advanced artillery knowledge did play a part, as it was his European-style battery that proved to be the most devastating during the bombardment. The Dutch discussed holding out and waiting for reinforcements, but ultimately walked out holding a white flag.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

Google unveiled an artificial intelligence tool Wednesday that its scientists said would help unravel the mysteries of the human genome — and could one day lead to new treatments for diseases. The deep learning model AlphaGenome was hailed by outside researchers as a “breakthrough” that would let scientists study and even simulate the roots of difficult-to-treat genetic diseases. While the first complete map of the human genome in 2003 “gave us the book of life, reading it remained a challenge,” Pushmeet Kohli, vice president of research at Google DeepMind, told journalists. “We have the text,” he said, which is a sequence of

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.

It’s a bold filmmaking choice to have a countdown clock on the screen for most of your movie. In the best-case scenario for a movie like Mercy, in which a Los Angeles detective has to prove his innocence to an artificial intelligence judge within said time limit, it heightens the tension. Who hasn’t gotten sweaty palms in, say, a Mission: Impossible movie when the bomb is ticking down and Tom Cruise still hasn’t cleared the building? Why not just extend it for the duration? Perhaps in a better movie it might have worked. Sadly in Mercy, it’s an ever-present reminder of just