It’s Saturday night at the HUNK club in Chengdu and men in gold lycra shorts and black boots dance on stage. They wear kimonos, in an apparent tactical compromise with new morality codes creeping into China’s “gay capital.”

But across town, young women still lounge on leather sofas drinking beer at a lesbian club, while a nearby bar is hosting an LGBTQ board game night.

Far from the administrative glare of Beijing, the cosmopolitan southwestern city, dubbed “Gaydu” by Chinese millennials, has long cherished its reputation as a safe haven for a community that faces stigma and widespread harassment elsewhere in the country.

Photo: AFP

But activists now say the city’s permissive streak is under threat, as the central Communist leadership puts the squeeze on the few bastions of sexual freedom across the country.

But Chengdu’s resilient LGBTQ community is not ready to be forced into the closet.

“There is some tacit acceptance by the authorities, but it is very delicate,” said Matthew, an activist from the NGO Chengdu Rainbow, who requested use of his first name only.

Photo: AFP

The recipe for survival, Matthew says, is “making small progress” rather than big political and social statements that rattle China’s hyper-sensitive authorities.

The mood in Chengdu started to sour in October when the MC Club was closed after explicit photos were posted online and local media reported that HIV infections had been linked to sex parties allegedly taking place at the venue’s sauna.

Some in the gay community say a spike in the number of domestic LGBTQ visitors — unable to travel overseas because of the coronavirus pandemic — drew unwanted attention from city authorities. Major gay bars in the city were temporarily shut down, ostensibly to control a public health crisis.

Then, an activist said all of the city’s LGBTQ organizations were suddenly investigated.

STOLEN PRIDE

China’s LGBTQ population still encounters discrimination and lacks legal safeguards in a country that as recently as 2001 still classified being gay as a mental illness.

Gay marriage is still not legally recognized, despite mounting calls to introduce it, especially among the younger generations.

But major obstacles block their progress.

President Xi Jinping (習近平) has overseen a drive against anything considered antithetical to Communist Party values — leaving little room for gay pride.

Beijing also frowns on large civil society mobilizations of any kind.

In August, ShanghaiPRIDE — China’s longest-running annual LGBTQ festival — abruptly announced it was shutting down for “the safety of all involved.”

No explanation was given for why the event was pulled, but rumors abound of pressure on the organizers as the LGBTQ community is boxed-in by conservative social values. To locals, Chengdu is the final holdout.

They say the city’s gay-friendly ambiance derives from its eclectic mix of ethnic minorities and cultures — as well as its handy distance from Beijing and the strictures of mainstream China.

The city’s allure is “its openness,” said activist Matthew, whose office is festooned with rainbow flags and posters reading “Be proud, Be yourself.”

“People here generally don’t care what your sexual orientation is.”

Before it was shut, the MC Club was packed with about 1,000 people each night, an activist said.

Its anything-goes reputation is folkloric across the gay community in the city of 16 million.

One gay man said he received a sexual massage in a sauna at the premises and had previously attended a party in the dark where no clothes were allowed.

TEA AND TOLERANCE

China’s first widely reported gay marriage took place in Chengdu in 2010 — a symbolic ceremony between two men as same-sex unions still have no legal basis.

Still, China’s rainbow community remains in the dark compared to many freer Asian countries.

Gay bars refused on-the-record interviews and most interviewees declined to be identified.

“These past few years, mainstream ideology became more aggressive and the LGBT community has been more marginalized,” said Tang Yinghong, a professor who teaches sexual psychology.

At HUNK club, there are no rainbow flags and most clubbers chat quietly, holding hands.

Its dancers have recently added the kimonos to their kit to avoid the unwanted attention garnered by the MC Club, a patron said.

Teacher Ray, who relocated to Chengdu this year, said he was uncomfortable with coming out at home in the northern city of Xian.

But “everyone in Chengdu knows I’m gay — my boss, some of my student’s parents, all of my friends.”

The secret to survival is avoiding noisy social and political advocacy, says Hongwei, a member of a Chengdu NGO, using a pseudonym.

LGBTQ groups in the city instead focus on community needs such as psychological support and help for those coming out, while some readily report planned events to authorities to keep everything above board.

At a trendy teahouse in the city center, same-sex couples nestle together in wicker chairs and sip tea, without raising any eyebrows.

“I never had anyone here tell me how to live,” says Hongwei, pouring out cups of green tea from a stylish black pot.

“We just manage our own business here, and don’t interfere with others.”

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

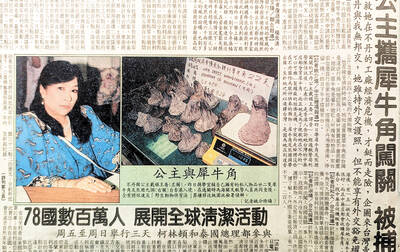

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted

The depressing numbers continue to pile up, like casualty lists after a lost battle. This week, after the government announced the 19th straight month of population decline, the Ministry of the Interior said that Taiwan is expected to lose 6.67 million workers in two waves of retirement over the next 15 years. According to the Ministry of Labor (MOL), Taiwan has a workforce of 11.6 million (as of July). The over-15 population was 20.244 million last year. EARLY RETIREMENT Early retirement is going to make these waves a tsunami. According to the Directorate General of Budget Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS), the