NOV. 23 to NOV. 29

Japanese researchers initially thought that the Saisiyat Aborigines’ Pasta’ay festival was a New Year celebration.

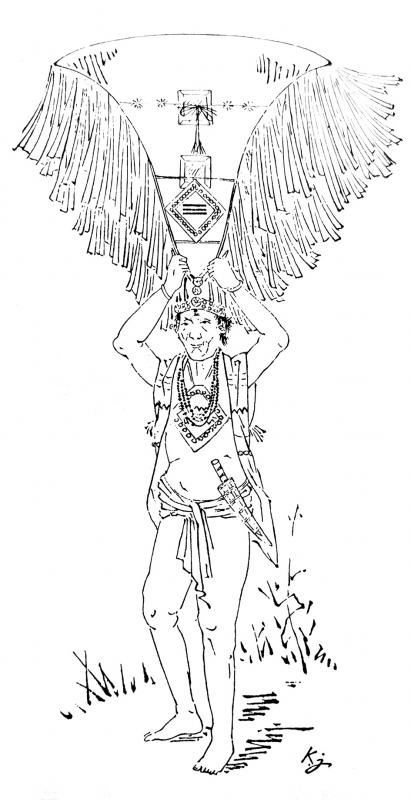

A drawing of a Saisiyat man dancing with a kirakil, a ceremonial headdress used during the Pasta’ay, appeared in a 1906 issue of Record of Taiwan’s Customs, where the author noted that it “represented reverence to their ancestral spirits.”

Photo: CNA

Ten years would pass before the Temporary Taiwan Old Customs Investigation Committee published the earliest description of the ceremony.

“The Pasta’ay is held to worship the Ta’ay people, who were a diminutive race living in the caves of the Maiparai Mountains,” the committee writes. “This group of short people became embroiled in a dispute with the [Saisiyat], who tricked them into plunging to their deaths in the river below … This festival is held to placate the souls of these short people.”

The appendix of the report elaborated on the story, describing the Ta’ay as a people shorter than 100cm but possessed great physical strength and magical powers. The Saisiyat were afraid of them, but invited them to join their annual ceremonies since they were good at singing and dancing. However, resentment arose when they found that some Ta’ay had raped their women. One day before the Ta’ay arrived, the Saisiyat booby-trapped the tree-bridge leading to their village, and all the Ta’ay perished save for two, who later taught them the songs used in the Pasta’ay festival to avoid disaster before they departed.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The report contains a second version of the story, where two surviving Ta’ay told the Saisiyat that due to their deeds, their crops would be damaged by mice and sparrows each year, and their raids on Han villages would fail.

Each version of the story seems to be slightly different — some say the Ta’ay taught the Saisiyat how to farm — but the general idea is the same. Both versions from the 1916 report indicate that a Saisiyat surnamed Jhu (朱) was the only one who mastered the difficult songs. The clan still runs the ceremony today; one of the few Aboriginal rituals in Taiwan that has not been discontinued at some point due to outside influence. It is now held every two years, with a major event held every 10 years.

The Pasta’ay was held this weekend in the two Saisiyat communities in Hsinchu County’s Wufeng Township (五峰) and Miaoli’s Nanjhuang Township (南庄), still following the schedule recorded in the 1916 report with the Miaoli group starting a day earlier.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

RESISTING ASSIMILATION

Han arrivals from China began pressuring the Saisiyat as early as the 1600s. Oral tradition has it that they once thrived on the coastal plains of today’s Hsinchu, Miaoli and Taichung counties, but their population was decimated after major clashes with the armies of the Tainan-based Kingdom of Tungning (東寧), which existed between 1661 and 1683. Scholars disagree on the exact details of the conflicts, but agree that the Saisiyat suffered much from these incidents.

Encroachment by Han settlers continued throughout the centuries, and by the time the Japanese took over Taiwan in 1895, the Saisiyat were already divided into the current two groups.

The Qing did not leave any records about the Pasta’ay, so little is known about the ceremony before the 1916 Japanese report. Tahes a Obay, a Wufeng Saisiyat, says in an oral history document from Taiwan Indigenous Culture Park that the ceremony was held every year up until 1936, when the Japanese government launched its kominka policy of assimilation.

The plan for the Saisiyat was to stamp out the Pasta’ay and force them to take up Shintoism. But Tahes’ father, a local policeman, learned of the plan and quickly informed the Jhu family, who swore to resist until the end rather than give up the ritual.

His father told the Hsinchu authorities that the Saisiyat would rather fight than comply, and that same year anthropologists Nobuto Miyamoto and Nenozo Utsurikawa arrived to film the ceremony on behest of the Saisiyat, who wanted to show the government the significance of the festival.

The anthropologists convinced the government to let the Saisiyat keep the Pasta’ay — if they also prayed at a Shinto shrine, Tahes says. But they reduced the duration of the ceremony and made them hold it every two years instead.

COMMERCIALIZATION

Although the Pasta’ay is one of the few Aboriginal ceremonies that endured throughout years of outside influence, the impact of tourism has been an ongoing concern.

According to a 1987 report by Chao Fu-min (趙福民), the local government started providing funding and “assistance” to the Hsinchu Saisiyat in 1984 in preparation for its major 10-year event in 1986.

“The government hopes to promote existing [Aboriginal] culture to preserve traditions and arts that are on the verge of disappearing,” Chao writes.

Chao says the ceremony then remained remarkably similar to the ones recorded in the Japanese documents. But the government asked the Saisiyat if they could “modify their songs and dances to add to the entertainment and tourism value of the ceremony,” a request that was turned down by all the elders.

Fu Jen Catholic University religious studies professor Chien Hung-mo (簡鴻模) writes in his 2007 book on Saisiyat religion that few people knew about the Pasta’ay before the advent of the media since it was held in a remote, hard-to-access area.

Between 1950 and 1980, the Hsinchu Saisiyat’s ceremony ground was located about an hour’s walk from the closest road. But by the late 1970s, tourists were already flooding the ceremony, leading to the construction of a new ceremonial ground that was about six times as large and accessible by car. The Miaoli Saisiyat also moved to a larger and more convenient location in 1976.

“Before, the Pasta’ay gave people a “mysterious, guarded” impression,” Chien writes. “Now it has lost much of its sacredness and solemnness and is becoming more and more tourist-oriented.”

Chien wrote that not only were there hordes of photographers mobbing the procession, the place was packed with stalls offering food, games, souvenirs and even Christmas decorations. Out-of-place lanterns and balloons lined the street, with heaps of trash left behind after the frenzy.

It’s impossible to return to the past and stop tourists from coming, but the Saisiyat have reiterated over the years that the Pasta’ay is not a celebratory event like a harvest festival, and hope that visitors remain respectful and do their research before attending.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them