Until this summer, when the idea of hiking the length of the island first occurred to me, I didn’t even know that Cijin (旗津) had been a peninsula until 1967. That’s when diggers and dredgers severed Cijin from Taiwan’s “mainland,” because the authorities wished to create a southern entrance to Kaohsiung’s fast expanding port.

The island is just under 9km long, but a bit of research quickly convinced me that a south-to-north trek wasn’t a good idea. The southern third of Cijin is dominated by container-lifting cranes, warehouses and other facilities off-limits to the public.

Dunhe Street (敦和街) forms the boundary between the inhabited section of Cijin and the freight-handling zone. Stepping off the bus, I walked through densely-packed neighborhoods, hoping to get a good look at the shipyards on either side of Jhongjhou Fishing Harbor (中洲漁港) and Jhongjhou Ferry Station (中洲輪渡站) on Cijin’s northern waterfront.

Photo: Steven Crook

The security guard at one yard told me I shouldn’t take photos. At another, three vessels were being worked on, but all of them were obscured by scaffolding.

Near the ferry dock, a few businesses sell mahogany-colored slabs of sun-dried salted mullet roe (烏魚子). This pricey delicacy, known as karasumi in Japan, is similar to the bottarga produced in several Mediterranean countries.

The backstreets and alleyways in this part of Cijin are incredibly warrenous, and I couldn’t locate the Chen (陳) ancestral hall marked on my map, nor the one for the Ye (葉) clan. I eventually stumbled across the Jhuang (莊) ancestral temple. It has three stories, making it one of the town’s taller non-shipyard structures. The extended Ye and Jhuang families figure prominently in the saddest episode in Cijin’s recent history.

Photo: Steven Crook

MEMORIAL PARK

Continuing along Cijin 3rd Road (旗津三路), I reached the Memorial Park for Women Laborers (勞動女性紀念公園). Visually, it’s unremarkable — the central feature is a pedestal the size of a squash court bearing a lotus sculpture — but the story behind it weaves ancient concepts and customs onto an industrial backdrop.

On the morning of September 3, 1973, Cijin residents boarded a boat to take them across the harbor to Kaohsiung Export-Processing Zone, where they worked in factories. The ferry was licensed to carry 13 passengers and two crew, but that morning 71 people squeezed aboard.

Photo: Steven Crook

The boat capsized, and 25 passengers drowned. All those who died were females aged 13 to 30. None of them earned more than NT$2,000 per month, and some were making as little as NT$900.

One Jhuang household lost three of their four daughters. Two other victims were Jhuangs. Six were surnamed Ye, while seven were Kuo (郭). The other 46, which included some men, were rescued.

When it emerged that every survivor was married, while those who’d perished were all single, “Many people… did not perceive this as a coincidence, but rather as a sign of supernatural significance” Anru Lee (李安如) and Wen-hui Anna Tang (唐文慧) write in a 2011 paper in the Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology).

Photo: Steven Crook

In Han societies, deceased maiden daughters have no place in the traditional scheme of ancestor worship. Every female, it was thought, should get married; at her wedding, she joins her husband’s clan for eternity.

It’s said that some girls who die unmarried haunt their families until their status is rectified. Some parents go so far as to place a red envelope on a road to entrap a male passerby, who is then browbeaten into becoming the bridegroom at a “ghost wedding.” If he refuses, the girl’s spirit may seek revenge.

Lee and Tang don’t mention any “ghost weddings” in the aftermath of the 1973 disaster, but they do explain how traditional notions featured in the girls’ funerals — and disturbed them even after interment.

Photo: Steven Crook

The accident might not have happened if officials had done their job, and the authorities initially refused to compensate the families of underage workers, saying they weren’t covered by labor insurance, so perhaps it was for fear of public anger that the Kaohsiung City Government worked with the victims’ families to find a plot of land where all 25 could be buried together.

During the funeral, the master of ceremonies announced that, in accordance with custom, the parents should “whip the coffins of their unfilial children who died before their aging parents.”

Proceedings halted while a man surnamed Jhuang, pleading that their daughters had been obedient girls who’d taken factory jobs for the sake of their families, tried (with some success, it seems) to persuade the other parents not to do this.

In 1988, when the original burial site was appropriated by the authorities, the graves were moved north to the current site of the Memorial Park for Women Laborers. This new location — initially known as the Twenty-Five Ladies’ Tomb (二 十 五淑女墓) — suffered repeated vandalism.

ANGRY GAMBLERS

Some of the damage, it’s thought, was inflicted by enraged gamblers who’d asked the deceased to give them hints as to winning numbers, but then lost. Such visitors often left behind cosmetics and other offerings. (Similar folk beliefs lead some to write down license-plate numbers of vehicles involved in accidents, and use them when buying lottery tickets.)

A karaoke business operating close to the tomb drew the ire of feminist groups, yet Lee and Tang noticed that family members of the 25 weren’t bothered by it. Some “seemed to even welcome it because the owner of the karaoke business helped to maintain the individual gravestones; he offered fresh flowers and paid tribute to those buried there...”

Between 2006 and 2008, as part of a government plan to develop Cijin for tourism, the individual graves were replaced by the current landmark. The bones of the deceased are stored in urns sealed beneath the pedestal.

The memorial park seeks to dispel what Lee and Tang call “the negative image attached to their maiden status,” and instead honor their contribution to Taiwan’s economic development. For the traditionally minded, however, government platitudes cannot resolve the anomalous position of a dead, unmarried female. Fortunately, popular religion came up with a remedy of sorts.

According to Lee and Tang, a dangki (童乩, spirit medium) revealed to the family of one of the 25 that their daughter had become a courtier of the Guanyin bodhisattva. She, and by implication the others, were no longer unmarried spirits, but on track to become minor deities.

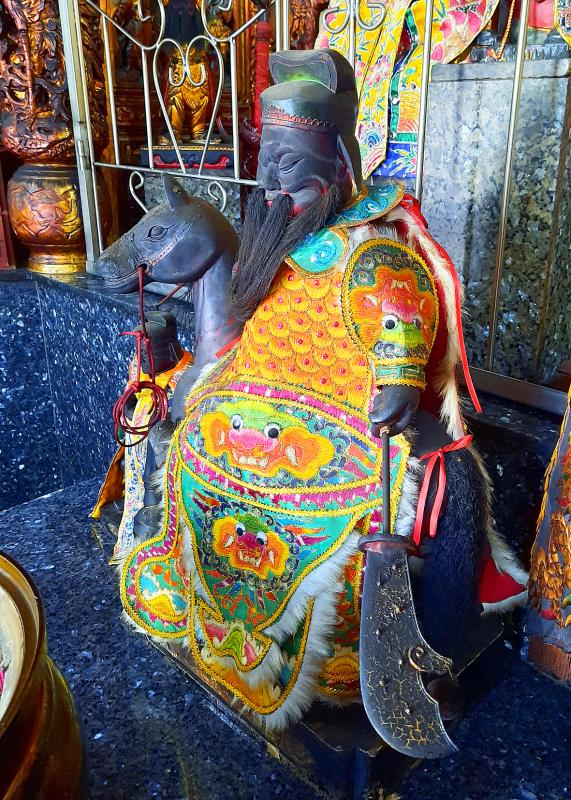

Individual deity statues were carved for each of the 25. Some were “welcomed into their fathers’ houses, placed on the family altar, and worshipped” — but not as ancestors. Others were entrusted to nearby halls of worship, including Baoan Jinshan Temple (保安金山寺) at 117 Jhongjhou 2nd Road (中洲二路).

I inspected every effigy and icon I could find at that temple, but couldn’t identify any that might represent a victim of the 1973 calamity. I hung around, hoping someone would help me out, but no one showed up.

Perhaps I should’ve asked the middle-aged couple I’d seen earlier at the memorial park. They approached from the south on a motorcycle, offered a quick prayer in the direction of the pedestal-tomb, then resumed their journey. Whether they see them as troublesome spirits, or respect them as hardworking heroines, it appears the local community hasn’t entirely forgotten the 25 girls and women.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide and co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

Taiwan’s democracy is at risk. Be very alarmed. This is not a drill. The current constitutional crisis progressed slowly, then suddenly. Political tensions, partisan hostility and emotions are all running high right when cool heads and calm negotiation are most needed. Oxford defines brinkmanship as: “The art or practice of pursuing a dangerous policy to the limits of safety before stopping, especially in politics.” It says the term comes from a quote from a 1956 Cold War interview with then-American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, when he said: ‘The ability to get to the verge without getting into the war is

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global