Although Tsai Fu-yi (蔡復一) left Kinmen as a child in the 1580s, his portrait remained a prized heirloom of the Caicuo (蔡厝) Tsai clan throughout the centuries. This Tsai clan retains to this day much of its ancient ancestral worship rituals, including an offering ceremony every anniversary of Tsai Fu-yi’s death.

On Wednesday last week, the Ministry of Culture officially deemed the painting of the Ming Empire politician “the oldest ancestral drawing in Taiwan,” designating it as the nation’s first ever significant national antiquity in an outlying island.

In 2016, two art historians concluded that the portrait is even older than a drawing of Ming Dynasty warlord Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功) on the list of national treasures. Tsai Fu-yi’s portrait is believed to have been completed around 1625, when Cheng was an infant.

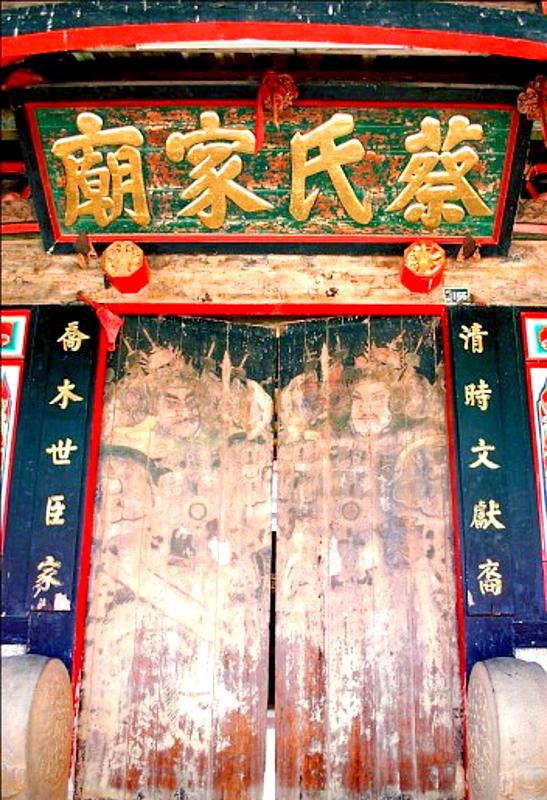

Photo courtesy of the Kinmen County Cultural Affairs Bureau

Tsai Fu-yi is the best-known member of the Caicuo Tsai clan. His contemporary Tsai Hsien-chen (蔡獻臣) from the nearby Cyonglin (瓊林) Tsai family was also a famous politician, and the two were known as the “Two Tsais of Tongan County” (同安二蔡), which during that time encompassed part of today’s Xiamen and all of Kinmen.

Since there’s much more information about the Cyonglin Tsai clan, and Tsai Fu-yi spent most of his life in China proper, this week’s column will focus more on the illustrious and better-recorded history of the Cyonglin Tsai family.

CLAN ORIGINS

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Caicuo Tsai clan’s progenitor Tsai Yi-lang (蔡一郎) allegedly settled in Kinmen from mainland Fujian Province near the end of the Song Dynasty, which was destroyed by the Mongols in 1279.

The Cyonglin Tsai clan, on the other hand, can trace their ancestry in Kinmen back to about 300 years earlier, when a portion of the family moved from Fujian to Kinmen. Around 1100, Tsai Shihchilang (蔡十 七郎) became the first of the Cyonglin Tsais when he married into the local Chen family. Five generations later, the Chens relocated elsewhere and left the land to the Tsais, where their descendents remain to this day.

Cyonglin was called Pinglin (平林) during Tsai Shihchilang’s time. According to modern-day descendant Tsai Ching-chi’s (蔡清其) historical account of the family, it was Tsai Hsien-chen who changed the village’s name to Cyonglin per the suggestion of the emperor in 1625.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Tsai Hsien-chen was one of six Cyonglin Tsai members to earn top three ranking in the imperial examination system during the Ming and Qing dynasties. According to Tsai Ching-chi, the family produced over 140 imperial scholars during the period, and commemorative plaques that hang in the shrine today speak proudly to this past success.

Life was not easy in Kinmen, and besides leaving the island to seek their fortunes elsewhere, the only other way to improve their lives was to do well in the imperial examinations — hence the heavy emphasis on education.

The clan also produced six military officers. The most famous is Tsai Pan-long (蔡攀龍), who was originally a poor fisherman. Seeing his great strength, his father-in-law recommended that he join the army, where he excelled. He rose through the ranks quickly, and in 1787 he led 700 men to Taiwan to help the Qing Empire quell the Lin Shuangwen (林爽文) rebellion. He served briefly as the military commander of Taiwan until he was further promoted. The Qing bestowed upon him baturu (hero) status and his portrait hangs in Ziguang Ge (紫光閣) in Zhongnanhai in Beijing as one of 20 “meritorious officers” who contributed to the “pacification of Taiwan.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

FOUR DISASTERS

Development History of the Tsai Family (蔡氏家族發展史) details four major disasters that befell the Tsai clan over the centuries. Around 1560, bandits from nearby Zhangzhou teamed up with Japanese pirates to take advantage of a weak and corrupt local military commander and invade Kinmen. Clan leader Tsai Hsi-tan (蔡希旦) recruited about 200 locals to defend the village, but they proved no match — although Tsai Hsi-tan reportedly was the only one not to flee from the invaders’ cannon fire. He was soon killed, and the invaders ravaged the island for two months before they left with the booty.

In 1662, the Ming loyalist and military commander Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功, also known as Koxinga) expelled the Dutch from Taiwan, intending to use it as a base to defeat the Qing Empire. Kinmen was under Cheng’s control at this time, but the Qing seized it a year later and forced all of its residents to move inland to prevent locals from supporting the rebels. In the ensuing chaos, hundreds of Tsai family members disappeared or died. They were not allowed to return until at least after the Qing destroyed Cheng’s Tainan-based Kingdom of Tungning in 1683.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

In 1817, a famine drove the Qing troops stationed on the island to raid Cyonglin, driving away its residents and seizing their possessions. The devastation was only ended when Tsai Shang-yuan (蔡尚轅) risked his life and traveled to Quanzhou to alert the government officials, who punished the offending soldiers. Tsai Shang-yuan remains a revered ancestor today due to this feat.

Finally, a case of the plague in 1946 killed over 100 Cyonglin residents. With the lack of medical expertise in the area, locals failed to quarantine the sick, which exacerbated the situation.

HEADING OVERSEAS

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

During the late Qing Dynasty, many Kinmen natives headed to Southeast Asia to seek their fortune, the fruits of which resulted in the construction of several Western-style mansions. Tsai Ching-chi counts at least 16 ancestors who made their fortune in Singapore and Malaysia, sending money home to expand the family shrine, build temples and set up schools.

The most prominent of these is his great uncle Tsai Chia-chung (蔡家種), who grew up poor and headed to Singapore in 1892 at the age of 19. After eight years of hard work, he returned home, paid off his father’s debts and married a local woman. He soon returned to Singapore and built up a successful business empire selling primarily salted fish and soap.

He was a widely respected philanthropist who had a knack for helping locals resolve their conflicts — including several large-scale armed clashes — and is remembered for sending thousands of bags of rice back to Kinmen during an inflation crisis in 1925. Unfortunately, he lost everything when the Japanese occupied Singapore in 1942, and he died shortly after.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Although President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) is of Hakka and Aboriginal descent and is not related to the Kinmen Tsais, she visited the Tsai family shrine in 2016 as a guest of honor at their ancestral worship festivities.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that either have anniversaries this week or are tied to current events.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a