Tunisia’s president has become a surprise champion of Arabic calligraphy in his country, shining a light on the artistic tradition as Arab states lobby for its recognition by UNESCO.

President Kais Saied sparked both admiration and mockery on social media when images emerged of hand-written presidential letters on official paper not long after he took office in October last year.

An academic with a keen interest in the art form, Saied had studied with well-known Tunisian calligrapher Omar Jomni.

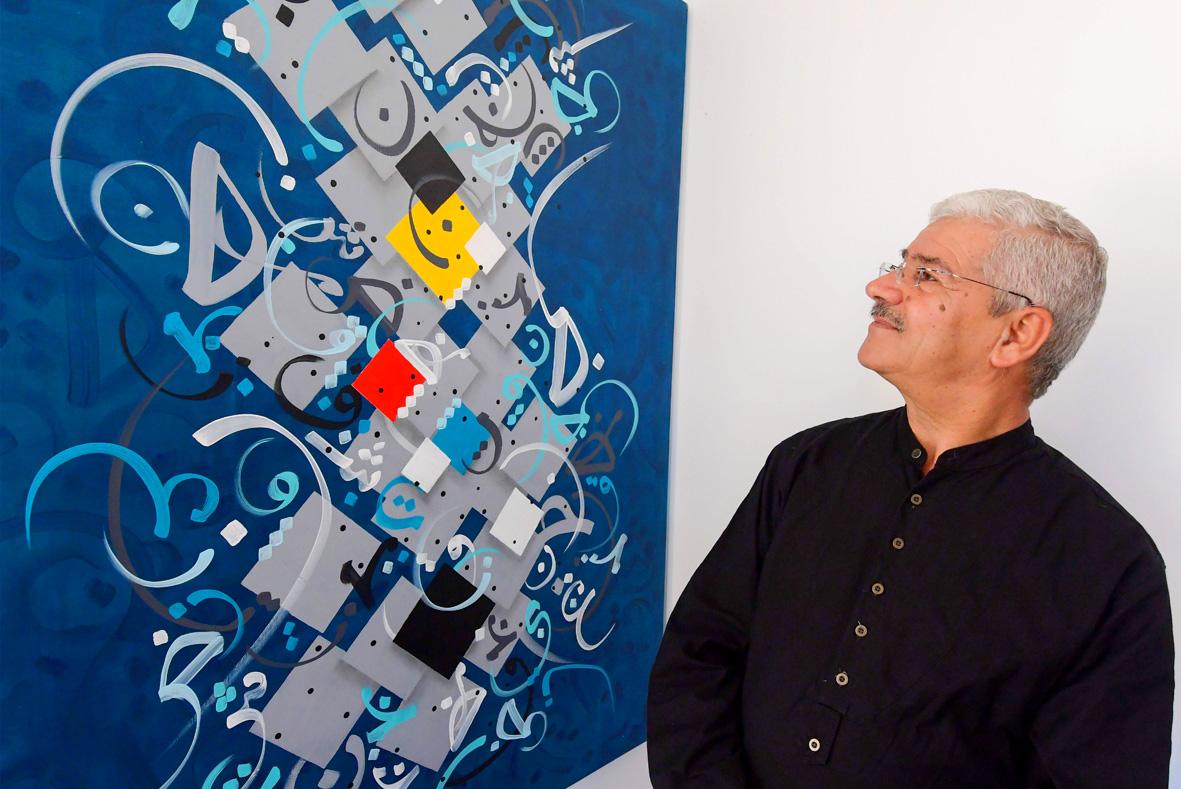

Photo: AFP

To prove that Saied had penned the documents himself, the presidency released a video showing him writing in a guest book. The president “writes official correspondence in maghrebi script and private letters in diwani,” Jomni said, referring to two forms of Arabic calligraphy.

Maghrebi script is a form of the older, angular style of Kufic calligraphy, while diwani is a more ornamental Ottoman style popular for poetry. The president’s “recognition” of calligraphy has warmed artists’ hearts, Jomni said, giving them hope for a brighter future for an art form that was like “a closed book.”

NOT JUST A ‘TECHNICAL SKILL’

Calligraphy in Tunisia lacks the prominence it enjoys in some other Arab countries — such as in the Gulf — and its National Center of Calligraphic Arts, created in 1994, risks closing its doors. With a lack of instructors, courses will likely have to end this year, according to the institute’s head, Abdel Jaoued Lotfi.

“There are not enough professional calligraphers in Tunisia,” said calligraphy master Jomni, who is in his sixties. “You can count them on one hand and they are working in precarious conditions.” Sixteen Arab countries, including Tunisia, Egypt, Iraq and Saudi Arabia, have prepared a proposal to have Arabic calligraphy inscribed on the UNESCO list of humanity’s intangible cultural heritage.

It’s a chance to consider calligraphy “as a whole culture and living heritage... and not just as a simple technical skill,” said Imed Soula, a researcher overseeing Tunisia’s submission to the UN cultural body.

He said Tunisia’s fading calligraphy practice, which traditionally saw artists tackle surfaces like copper or stone, was also linked to the growing use of new technologies, some of which have moved it away from its performing-art dimension.

But Jomni said calligraphy in Tunisia suffered from “the brutal and chaotic marginalization of Islamic culture during the ‘60s, whose repercussions we still feel today.”

UPDATING TRADITION

The country’s first president, Habib Bourguiba (1957-1987), dismantled and divided up the Islamic University of Ez-Zitouna after a power struggle with its clerical leadership.

Books and manuscripts from the institute, then Tunisia’s main Arab-language university and one of the most important in the Muslim world, were seized. Tunisian calligrapher Mohamed Salah Khamasi studied there at the start of the 20th century and laid down the foundations for calligraphy in the country, passing his knowledge on to several generations.

Following the 2011 revolution that set Tunisia on the road to democracy, a young generation of calligraphers is now calling for a reinvention of the art form to reflect the spirit of the times — “so that it doesn’t get rusty and outdated,” Karim Jabbari said.

The artist in his thirties is known internationally for his large-scale calligraphy works, often created with light using long-exposure photography, or in mural form.

In 2011, in his marginalized hometown of Kasserine, which saw deadly clashes before the fall of longtime autocrat Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, Jabbari used light to write the names of protesters in the places where they were killed.

“Through this form of calligraphy, I want to highlight the beauty of the Arabic language and bring it closer to people,” Jabbari said — and “keep our heritage firmly anchored in our memory.”

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is