Over the past few years, I’ve grown to really appreciate Liouguei District (六龜). It’s one of the most scenic and thinly populated parts of Kaohsiung.

The number of humans living here has steadily declined since the 1980s. With barely 12,500 adults and children spread over 194 square kilometers, Liouguei’s residents enjoy more space per person than folks in Hualien County.

Liouguei is dominated by the Laonong River (荖濃溪), a major tributary of the Kaoping River (高屏溪). Within the district, there are four river crossings. Three are part of the provincial highway network; the fourth belongs to Kaohsiung Local Road 131.

Photo: Steven Crook

Following up on a brief visit a few weeks earlier, I recently drove along Provincial Highway 20 into the northern part of the district, then turned south onto Provincial Highway 27. I found the turnoff and bridge for Local Road 131 about 6km from the intersection of highways 20 and 27.

On the western side of the Laonong River, the road worked its way through a small village before entering a tract of beautiful back country. This, I’d learned from a road sign on my previous visit, is the Colorful Butterfly Valley Scenic Area (彩蝶谷風景特定區).

The scenic area comprises 485 hilly hectares of brushy woodland dotted with stands of teak and kassod. It’s not a single valley, but rather eleven interconnected drainages. Several of the streams dry up during the cool season, but there’s usually water in the Hongshuei Creek (紅水溪) and the Jhujiao Creek (竹腳溪).

Photo: Steven Crook

More than 250 butterfly species have been recorded here, and it’s said that pretty much anytime between March and October you can expect to see a good number and variety of lepidopterans. From what I saw, I wouldn’t consider it much of a butterfly hotspot, certainly when compared to the Purple Butterfly Valley (紫蝶幽谷) in Maolin (茂林), 16km to the south. But it’s a delightful and highly accessible patch of nature.

Following Local Road 131 brought me to the back of a major temple I’d seen in the distance on my previous visit. I entered the grounds of Di Yuan Temple (諦願寺, literally “temple of hope”; open 4am to 8.30pm daily) without any expectations. Yet its location, overlooking and within a javelin throw of the Laonong River, is both commanding and vexing.

Having experienced a few of the typhoons and earthquakes that have ravaged Taiwan, I looked at this modern Buddhist complex and asked myself: Despite the concrete that’s been poured over the riverbank — and the prayers for protection that have surely been offered — how would it fare in a natural disaster?

Photo: Steven Crook

That question has already been answered, I learned after I got home. The groundbreaking ceremony was held back in 1996, but the first of three phases of construction wasn’t completed until 2016. A lack of funding was one reason for the slow progress. Another was that major repairs were needed in 2009, following Typhoon Morakot.

Walking from the parking lot and into the courtyard behind the main shrine, I encountered something I’ve never before come across in a place of worship: A pair of large and aggressive dogs.

The moment they saw me, these canines decided they didn’t like me one bit. I spent the rest of my visit looking around corners before making any moves.

Photo: Steven Crook

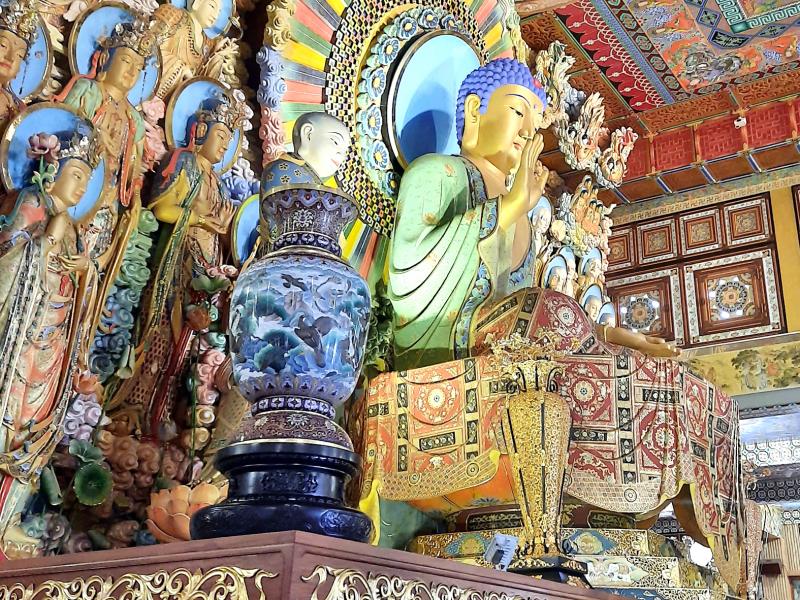

Externally, Di Yuan Temple isn’t very different to many other religious sites in Taiwan. Internally, however, there are several interesting features.

The main hall is gloriously colorful, and the Shakyamuni Buddha has a head of vividly blue curls. Hair of this hue is one of the Buddha’s 32 distinguishing physical characteristics. Next to the altar, there’s a concert piano. I don’t think I’ve ever witnessed a Buddhist service that included piano music.

On the far left of the hall, I found a Fasting Siddhartha statuette, and learned from it that in Chinese this kind of icon is called “Six Years of Austerity” (六年苦行). During the spiritual quest, preceding his enlightenment, the Buddha devoted six years to intense mental concentration and cutting all attachment to physical senses. It’s said that, toward the end of this period, he survived on a single grain of rice per day, and became skeletal thin.

Photo: Steven Crook

Behind the blue-haired Shakyamuni Buddha, 33 representations of Guanyin (觀音) face the back door. In Buddhism in Taiwan and China, this bodhisattva of mercy and compassion is female; elsewhere, he/she is usually regarded as male.

The central image is about the size of an adult and shows Guanyin sitting on a huge fish. This alludes to a story in which she appears in a market as a beautiful young woman holding a basket of fish, and requests that the men who admire her prove their worth by memorizing Buddhist sutras. It’s a very fine and intricate piece of work — but I was distracted by the bodhisattva’s enormous clodhopping feet, the significance of which I’ve not been able to discover.

Another highlight within the complex is a striking Reclining Buddha. Weighing seven tonnes, 7.5m in length, and carved from a single camphor tree, it’s claimed to be the largest camphor-wood Buddha in East Asia. An adjacent chamber held a somewhat smaller Buddha, also reclining and still wrapped in plastic.

Photo: Steven Crook

A patch of land near the parking lot is populated by gray statues of arhats, individuals who have made great progress toward enlightenment, but have not attained a state of Buddhahood.

One online source puts the number of arhat statues beside Di Yuan Temple at “more than 500,” and points out that no two are the same. Each statue bears a number, but I didn’t see a master list anywhere. Serious Buddhists may look askance at my choosing a favorite arhat. But who can resist the charm of the bald-headed gentleman who, while in deep contemplation, strokes his waist-length eyebrows?

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide and co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand