Within 10 minutes of the train pulling into Chaojhou (潮州) in Pingtung County, I’d retrieved my bike from a paid-parking compound and initiated the fitness tracking app on my phone. Just one thing bothered me: The color of the sky.

I cycled southeast, passing the shuttered Dashun General Hospital (大順醫院). Given everything that’s going on in the world, I couldn’t help but think: If the government needs extra facilities to handle the COVID-19 epidemic, this sizable building could perhaps be brought back into service.

After crossing Highway 1 (台1線), I skirted a settlement established after 2009’s Typhoon Morakot disaster, during which mountain villages throughout the south were devastated by floods and landslides. Whereas most of Chaojhou’s residents are Hakka, the families who’ve moved into New Laiyi (新來義部落) in Sinpi Township (新埤鄉) since 2012 are indigenous.

Photo: Steven Crook

Taking Road 185, I headed southeast across the Linbian River (林邊溪) and into Siangtan (餉潭). I kept going through the heart of the village — which is big enough to have its own elementary school and police station — to Longtan Temple (龍潭寺). I felt a few drops of rain when I paused by the pond in front of the shrine. Judging by the trash around the water, people often come here to engage in the secular pursuits of smoking and drinking.

I didn’t expect much of the temple, so I wasn’t disappointed. There’s nothing remarkable about the building or its hilly backdrop. Proceeding north on County Road 113 (屏113), I hadn’t got more than 1km when a spatter of rain developed into a heavy shower. Rather than stop and throw on my anorak, I decided to keep going in the hope I’d find shelter just around the corner.

Wet through at the shoulders and knees, I trespassed onto a hillside farm where tarpaulins kept a table and a few chairs dry. I didn’t see anyone, so I sat down and watched the ground turn to mud.

Photo: Steven Crook

Three-quarters of an hour later, when the rain eventually eased off, I witnessed something I’ve seen before in similar conditions: Hundreds of dragonflies, appearing out of nowhere, buzzed energetically at head height for several minutes before dispersing.

Passing pineapple fields, mango orchards, and papaya plantations, I continued north on County Road 113. An ornate archway decorated with indigenous motifs prompted me to make a quick detour to the community known to Mandarin-speakers as Wenle (文樂部落), and to Paiwan folk as Pucunug. In the village itself, I’m sad to report, there’s nothing half so appealing as the arch.

I was now in Laiyi Township (來義鄉), where I planned to visit another four villages. But first I needed to refuel. After grabbing some rice and soup in Gulou (古樓), the busiest part of the township, I recrossed the river, hoping to take County Road 113 inland to its eastern end, then return via County Road 110 (屏110) on the north side of the river.

Photo: Steven Crook

Before I got far, a sign told me the road was closed. However, I could see asphalt extending around the corner, so I persevered. Finding the surface too slick for safe riding, I pushed on, figuratively and literally. Within a few hundred meters, the road disappeared beneath rocks and I admitted defeat. I hadn’t wasted much time, and the views up and down the valley had been pretty good.

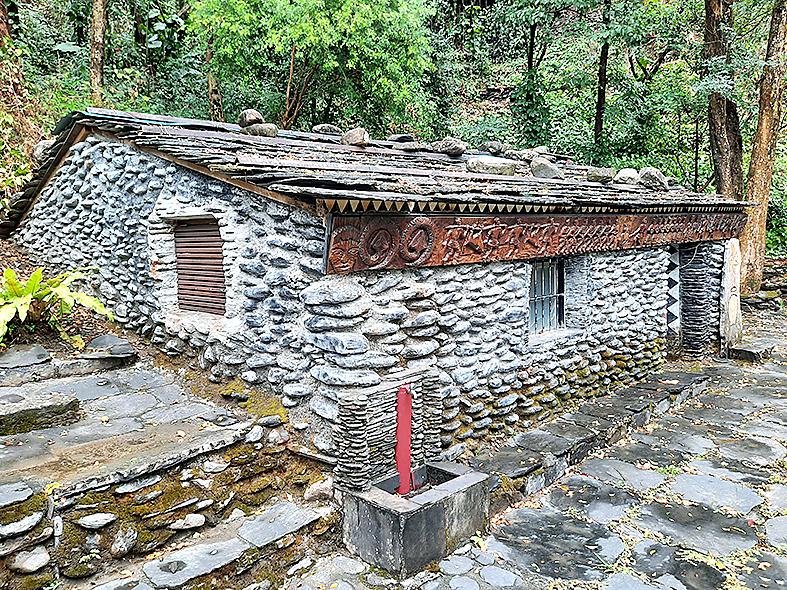

Siljevavaw Forest Park (喜樂發發森林公園), just east of Laiyi Elementary School (來義國小) on County Road 110, is an attractive spot. It’s no bigger than many city parks, but contains photogenic indigenous architecture and art.

A bust near the entrance honors Japanese hydraulic engineer Torii Nobuhei (1883-1946). I wasn’t familiar with his name, but from the Chinese-language plaque I gleaned that he’d planned and overseen the construction of key water-supply infrastructure in the valley. He is to the development history of the Chaojhou-Sinpi region what Yoichi Hatta is to the Chianan Plain (嘉南平原).

Photo: Steven Crook

The next stretch involved some uphill effort, but soon I was riding through the narrow streets of the village from which Laiyi Township takes its name. Three things made an immediate impression on me. First, even though part of the population has relocated to New Laiyi, there seemed to be quite a few people around. Second, rather than use Mandarin or Taiwanese, many residents were chatting to each other in Paiwan. Third, dead earthworms littered the road.

I scanned the hillside to the east for the ruins of Old Laiyi (舊來義), but didn’t see anything that resembled its old slate houses. Having run out of ridable road, I locked my bike and set off on foot along the riverbed.

Two pairs of towers are all that remain of suspension bridges. During the hour I spent hiking by the river, I came across numerous chunks of concrete, girder fragments, and other evidence of Mother Nature rejecting humanity’s efforts to penetrate the mountains.

Freewheeling back to Gulou took mere minutes, and where the townships of Laiyi, Sinpi, and Wanluan (萬巒) converge, I stopped at the first convenience store I’d seen in hours. Suddenly, I had to share the road with a dozen cars and just as many motorcycles.

I was back in the lowlands, that was for sure. At this point in the story, you might expect a lament on the themes of overcrowding and air pollution. But I made a point of staying off major roads as I approached the railway station at Sishi (西勢) in Jhutian Township (竹田鄉), and enjoyed the final third of the day’s ride (which totaled 64.7km) as much as the earlier parts.

Near Chihshan (赤山), I stumbled across a stretch of old Taiwan Sugar Corporation (台糖, TSC) railroad that’s being converted into a bicycle path. Avoiding the heart of Neipu (內埔), I joined County Road 48-1 (屏48-1), a route I hoped would go through quiet yet quaint villages.

I guessed right. Where County Road 48-1 is also known as Liren Road (里仁路), I stopped to gawk at a picturesque ruin and the exceptionally colorful shrine cater-corner from it. A septuagenarian on a bicycle pulled up, and asked me if I wanted to buy a house. I replied that I just wanted to take photos — but I’ve long thought this corner of Pingtung County could be a great place to call home.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture, and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai, and author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide, the third edition of which has just been published.

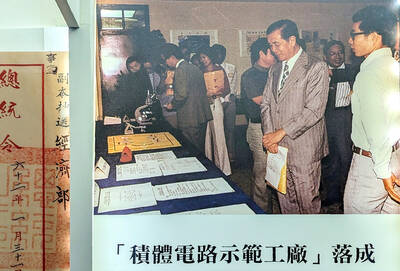

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

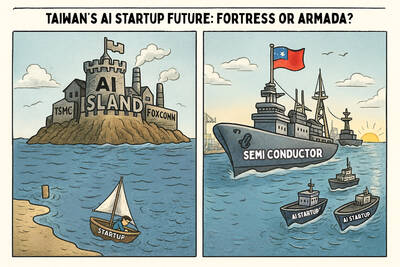

President William Lai (賴清德) has championed Taiwan as an “AI Island” — an artificial intelligence (AI) hub powering the global tech economy. But without major shifts in talent, funding and strategic direction, this vision risks becoming a static fortress: indispensable, yet immobile and vulnerable. It’s time to reframe Taiwan’s ambition. Time to move from a resource-rich AI island to an AI Armada. Why change metaphors? Because choosing the right metaphor shapes both understanding and strategy. The “AI Island” frames our national ambition as a static fortress that, while valuable, is still vulnerable and reactive. Shifting our metaphor to an “AI Armada”

The older you get, and the more obsessed with your health, the more it feels as if life comes down to numbers: how many more years you can expect; your lean body mass; your percentage of visceral fat; how dense your bones are; how many kilos you can squat; how long you can deadhang; how often you still do it; your levels of LDL and HDL cholesterol; your resting heart rate; your overnight blood oxygen level; how quickly you can run; how many steps you do in a day; how many hours you sleep; how fast you are shrinking; how

“‘Medicine and civilization’ were two of the main themes that the Japanese colonial government repeatedly used to persuade Taiwanese to accept colonization,” wrote academic Liu Shi-yung (劉士永) in a chapter on public health under the Japanese. The new government led by Goto Shimpei viewed Taiwan and the Taiwanese as unsanitary, sources of infection and disease, in need of a civilized hand. Taiwan’s location in the tropics was emphasized, making it an exotic site distant from Japan, requiring the introduction of modern ideas of governance and disease control. The Japanese made great progress in battling disease. Malaria was reduced. Dengue was