March 16 to March 22

Thousands of angry supporters surrounded the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) headquarters on March 19, 2000, clashing with the police late into the night. The banners and posters they brought delivered their message loud and clear: “Lee Teng-hui is a traitor!” “Lee Teng-hui has swindled the loyal and steadfast KMT members!” “Lee Teng-hui, resign immediately!”

Lee, who was still the nation’s president, barely escaped from the building after riot police and water cannon trucks cleared his path — but not before one of his advisors was beaten up.

Photo courtesy of Open Museum

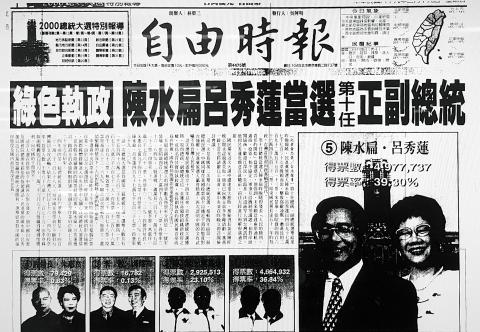

He officially stepped down as KMT chairman five days later as the protests continued, stating that he must take responsibility for the KMT’s ouster from power after ruling Taiwan for more than 50 years. Lien Chan (連戰), the party’s presidential candidate, finished last in a tight three-way race on March 18 with 23 percent of the vote.

Many of the protestors were supporters of ex-party member James Soong (宋楚瑜), and they blamed Lee for the KMT’s loss by insisting on the less popular Lien as the party’s candidate. The charismatic Soong declared that he would run as an independent candidate, eventually picking up 36 percent of the vote — just 3 percentage points behind the winner Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Some were convinced that Lee threw the election because he wanted Soong to lose. Others accused him of wanting Chen to win because he secretly harbored ambitions for Taiwanese independence.

On March 31, Soong announced the formation of the People First Party (親民黨). He would participate in every presidential election since then except for 2008.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

FREEZING THE PROVINCE

Soong was once Lee’s close ally, supporting Lee’s consolidation of power after former president Chiang Ching-kuo’s (蔣經國) death in 1988. In turn, Lee appointed Soong party secretary-general in 1989 and provincial governor in 1993. Soong retained his position in 1994 by winning the first provincial governor election in Taiwan.

But ever since the KMT lost China to the Chinese Communist Party 1949, the Taiwan Provincial Government and the central government essentially ruled the same territory, with 98 percent overlap.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Part of why the provincial government existed was to substantiate the KMT’s claim that it remained the legitimate ruler of China, and would return one day. But the government body’s existence was eating heavily into the nation’s resources and complicating the bureaucracy. Furthermore, when the provincial governor was appointed there was little conflict between the two bodies. But with the position now being elected, clashes emerged.

In fact, mboldened by the support of his constituents, Soong reportedly began criticizing the central government over resource allocation for public works in a year of natural disasters, as well as other issues. Coupled with his popularity, leaders in the central government started worrying about the “Boris Yeltsin Effect” — referring to a confrontation between a president and an immensely popular local leader.

In late 1996, Lee brought up the idea of downsizing the Taiwan Provincial Government, which Soong strongly opposed. The DPP, who favored Taiwanese independence, of course would agree to cooperate, as getting rid of the province designation would be a first step.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Lee assured Soong that the decision was purely political and not personal, but Soong resigned in protest. Lee declined to accept and Soong returned to office the following month, but the rift between the two kept widening as the downsizing proceeded. The elections for provincial governor as well as assembly were suspended, making Soong the first and last of his kind.

DIVIDING THE VOTES

Soong didn’t announce his bid for president after he served out his provincal governor term in 1998, but polls showed that he had the most support among the people as he was much more capable and charismatic than Lien. By early 1999, it seemed possible that there might be a Lien-Soong ticket, but talks eventually fell through. (The two parties would join forces in 2004 against the DPP).

Despite the KMT naming Lien as its candidate, Soong also declared his bid for the presidency, and was expelled from the party in November 1999 along with six of his close aides. Many KMT heavyweights also announced their support for Soong, leading to a major split in the party. This would be the party’s second fracturing since those opposing Lee formed the New Party (新黨) in 1993, but one that was much more devastating.

On a side note, the DPP also had its own drama. Former chairman Hsu Hsin-liang (許信良) quit the party in May 1999 to run as an independent after Chen secured the nomination. Hsu barely made a dent, earning just 0.63 percent of the vote.

Soong was still the favorite as an independent candidate, but in December 1999, KMT legislator Yang Chi-hsiung (楊吉雄) accused Soong of embezzlement in a bid to destroy his image. The charges were later dropped, but Soong’s popularity took a hit, and suddenly the race became a tight one between him and Chen.

Several other factors boosted Chen’s popularity. Academia Sinica president Lee Yuan-tseh (李遠哲) and several other prominent public figures, including Cloud Gate Dance Theatre (雲門舞集) founder Lin Huai-min (林懷民), formed a non-official National Policy Advisory Committee in support of Chen.

As usual, the DPP also got a boost after then-Chinese premier Zhu Rongji (朱鎔基) threatened Taiwanese to vote with caution three days before the showdown, stating: “Nothing good will happen to anyone who advocates Taiwanese independence,” “Don’t act on sudden impulse, or you will regret it” and “There are three days left and nobody can predict the future. Our Taiwanese compatriots, you must be careful!”

And with that, the KMT’s fate of losing power for the first time in 55 years was pretty much sealed.

“We used to think of the Kuomintang as this huge, powerful party,” James D. Seymour, a senior research scholar at the East Asian Institute of Columbia University, told the New York Times. “But we found out this weekend that the emperor has no clothes.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

Lines between cop and criminal get murky in Joe Carnahan’s The Rip, a crime thriller set across one foggy Miami night, starring Matt Damon and Ben Affleck. Damon and Affleck, of course, are so closely associated with Boston — most recently they produced the 2024 heist movie The Instigators there — that a detour to South Florida puts them, a little awkwardly, in an entirely different movie landscape. This is Miami Vice territory or Elmore Leonard Land, not Southie or The Town. In The Rip, they play Miami narcotics officers who come upon a cartel stash house that Lt. Dane Dumars (Damon)