March 9 to March 15

All was calm in Hualien County’s Fenglin Township (鳳林) when the 228 Incident broke out in Taipei. Far from the chaos and without a radio, Chang Yi-jen’s (張依仁) family didn’t hear about the anti-government uprising on Feb. 28, 1947 until a family friend visited them shortly after and warned them to stay quiet and lie low.

On April 4, about 10 armed soldiers burst into the family home, tying Chang and his father Chang Chi-lang (張七郎) up and carting them away. The same day, they also arrested Chang’s two brothers, Chang Kuo-jen (張果仁) and Chang Tsung-jen (張宗仁), who had just attended a banquet to welcome the troops to town in place of his ailing father.

Photo: Chien Hui-ju, Taipei Times

Chang Yi-jen was the only one of the four to survive the ordeal. The others were found on April 6, stripped to their underwear and shot twice each, with obvious signs of torture. Chang was released three months later without being questioned, and faced the task of supporting his mother, his dead brothers’ widows and children as well as two younger brothers who were still in school.

This was one of the higher profile tragedies to fall upon Taiwan’s east coast in the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) brutal suppression of the uprising. While there was relatively little unrest in the area, reinforcement troops from China landed in Keelung on March 8 and wreaked havoc there before making their way down the coast, where they arrested hundreds of people in Yilan County, executing over 20 before landing in Hualien on April 1.

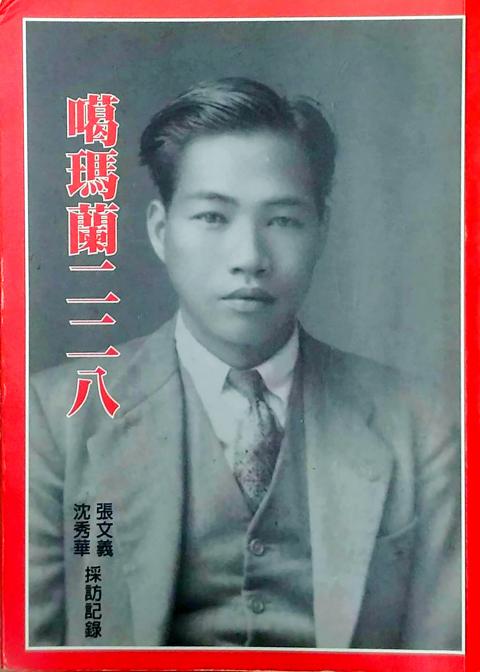

“Some say that Yilan was neither the center of the 228 Incident, nor did many people die. But historic tragedy is not just about the numbers. When dealing with this kind of brutal, inhumane, unjust killing without any public trial, even one victim is too much,” writes Chang Wen-yi (張文義) and Shen Hsiu-hua (沈秀華) in the book Kavalan 228 (噶瑪蘭二二八).

Photo: Hua Meng-chin, Taipei Times

HUNDREDS ARRESTED

According to Kavalan 228, news of the uprising reached Yilan, which was difficult to access, within two or three days. Most of the China-born officials and residents went into hiding, and unlike the situation in Chiayi, where they were beaten on sight, they received help from locals who sought to keep the peace.

Prominent residents in each town put together committees to deal with the situation. While there was debate whether to partake in the uprising, they managed to avoid bloodshed across the county aside from minor skirmishes. But by March 10 or 11, the troops arrived to “restore order.” Everything went back to normal at first with the officials resuming their posts and the committees disbanding, but the soldiers soon began the arrests.

Photo: Yu Tai-lang, Taipei Times

It’s not clear how many died, but the author interviews 13 relatives of the victims and 13 witnesses to provide a glimpse into the events that transpired.

Yilan Hospital director Kuo Chang-tan (郭章坦), who had just moved to the area in 1946, was pushed into a leadership role by locals after the 228 Incident. The official reason was his neutrality as an outsider, but his daughter Kuo Sheng-hua (郭勝華) suspects that the other candidates just didn’t want the responsibility.

Soon, word spread that the government troops were coming to arrest all those involved with the various 228 Incident committees, and many townspeople urged Kuo to flee. With his wife pregnant and confident that he didn’t do anything wrong, Kuo declined.

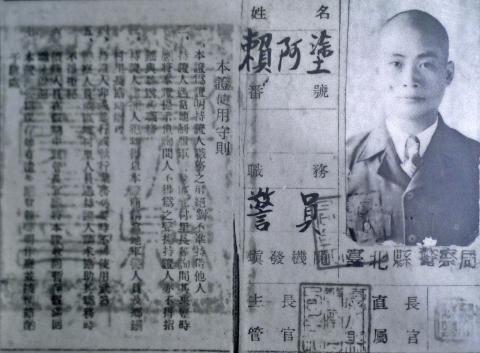

Photo courtesy of Lai Wu-chen

In the wee hours of March 18, soldiers smashed the windows of the Kuo residence and took him away. They found his body buried in front of a temple several days later with a single shot to the heart.

By contrast, Lin Tsai-ling (林蔡齡), a manager at Bank of Taiwan’s local branch, suffered the same fate despite reportedly not being involved at all. Kuo and Lin’s descendants wonder in the book if the victims had offended someone in the government earlier and this was just an excuse to exact revenge. Kuo may have argued with Yilan’s mayor over hospital issues, and Lin may have drawn the ire of local soldiers by refusing to let them withdraw money without proper procedures. The sister-in-law of Chen A-sung (陳阿鬆), another victim, was also convinced that he was killed due to an earlier dispute with a policeman and a local family. But nobody knows for sure.

Some of the victims were just ordinary people who were just going about their lives — Cheng Huo-tu (鄭火土), a fish vendor in Luodong (羅東) township, was allegedly arrested just because he was walking in a group of more than three people. The family was told to collect his body, his hands tied behind his back with wire piercing his palms, on March 24.

Photo: Chiang Ming-chih, Taipei Times

Factory worker Wu Nan’s (吳南) three brothers had already been taken away when a wanted man he didn’t know very well tried to seek refuge in his house. The troops ordered them outside and shot both men on the spot. About three weeks later, two of the brothers returned home safely — the third was considered to have “too strong of a Japanese spirit” and was sent to a reeducation program for six months.

MARKED FAMILY

Events in Hualien followed a similar trajectory to Yilan, and by the time the troops got there on April 1, the committees were able to keep things under control. But again, that failed to prevent the soldiers from making arrests.

The only victims mentioned in the book Hualien Fenglin 228 (花蓮鳳林二二八) were the three members of the Chang family. The family had suffered misfortune at the hands of rulers before — Chang Yi-jen’s grandfather and two adopted sons were killed by Japanese soldiers arriving to take over Taiwan in 1895. Chang and his brothers were educated in Japan and found work in Japan-occupied Manchuria, only returning home after World War II.

Chang stresses that his father did not participate in any of the 228 Incident committees because he was sick at that time. He is convinced that his father was killed because he spoke out in front of the National Assembly against Taiwan governor-general Chen Yi’s (陳儀) decision to tax the Taiwanese after initially promising not to do so.

“I’m very sure the central government ordered his killing,” Chang says, noting that the military seemed to come to Fenglin specifically to kill his family members and left abruptly after. He would meet a member of that division years later, who told him that he was just following orders. Chang was spared because he once served as a military doctor.

The case is often tied to then-Hualien county commissioner Chang Wen-cheng (張文成). Chang Wen-cheng and Chang Chi-lang did have their disputes, but Chang Yi-jen doubts that a county official would have the power to order the military to kill an assemblyman.

In the following years, after he relocated to Tamsui and opened up a clinic, Chang says the government special agents and police would visit him several times per month in the middle of the night, asking him all kinds of questions and looking through his belongings. Fed up with the situation, Chang fled to Brazil via Japan in the early 1960s, not setting foot in Taiwan for the next 22 years.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.