Surfboard tucked under his arm, Dery Setyawan sprints into the crashing waves. It is not just a physical challenge but an emotional one — most of his family and friends were swept to their deaths when a tsunami hit these shores 15 years ago.

His hometown of Lampuuk was almost destroyed entirely, but despite his devastating loss, the father-of-two sees the water as a way to heal.

“Surfing has been the best cure for my tsunami trauma. When I am on the waves, all my fears are gone and I can embrace the past and be at peace with it,” he says.

Photo: AFP

On Dec. 26, 2004, a monstrous 9.3 magnitude quake struck undersea off the coast of Sumatra. It sparked a tsunami nearly 100 feet (30 meters) high that killed more than 220,000 across a string of Indian Ocean countries, including Thailand, Sri Lanka and India.

Reaching as far as East Africa, the tsunami unleashed energy equivalent to 23,000 of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima — and is considered among the deadliest natural disasters in history.

Indonesia was hardest hit with at least 170,000 killed, though the true death toll is likely to be higher as many bodies have yet to be recovered or identified.

Photo: AFP

The Indonesian city of Banda Aceh reported the highest number of casualties. Hastily dug mass graves are still being uncovered from this area with dozens of bodies pulled from the ground over the past year, including a woman whose driver’s licence was still in a wallet tucked into her pants pocket.

For Setyawan and others from Lampuuk, just outside of Banda Aceh, surfing has become a way to help them start again.

“Water is part of our lives here. This is where we live, interact with family and others and make money for living,” the 35-year-old father tells AFP as the disaster’s anniversary approaches.

MASS GRAVES

His town was almost lost as the towering waves crashed ashore, ripping palm trees from the roots and flattening buildings.

Of Lampuuk’s 7,000 residents — just 300 survived. Setyawan’s mother, two grandmothers and infant brother were all killed, along with many of his friends. He remembers the water crashing into his home the force dragging him some 200 meters till he hit some debris and clung on for his life. In years immediately following, the surviving residents were fearful of the water.

“We’d only look at the waves just to check whether the water level had gone down,” Setyawan said, referring to a tell-tale sign that a tsunami may be approaching.

But after the first anniversary of the disaster, Setyawan decided to face his fears. He went back into the water.

“Waves from the beach are our friends, the ones that killed people during the tsunami were from the deep ocean. That was how I convinced myself before getting in for the first time,” he recalls. Now a professional surfer, he’s competed in international and domestic competitions, and organised last month’s Aceh Surfing Championships.

Today, Lampuuk has been rebuilt with tsunami evacuation signs everywhere. The population has grown to 2,000 — still a far cry from its original population, but Setyawan aims to transform the shores from a place of despair to one of hope.

He also formed a local surf club and set up a beachfront restaurant, and is confident of the tourism potential.

“Surfing is one way of attracting people to come to this place again after the tsunami,” Setyawan says.

‘ANOTHER WOUND’

Volcano-dotted Indonesia is one of the most disaster-hit nations in the world due to its position straddling the so-called Pacific Ring of Fire, where tectonic plates collide.

Three natural disasters last year hit the Southeast Asian archipelago in six months. A tsunami, triggered by an earthquake, hit Palu on Sulawesi island killing 2,200 with thousands more missing and presumed dead.

Hundreds died after a series of powerful earthquakes on the island of Lombok and then in December another tsunami, this time caused by a volcanic eruption, struck the coastal regions in the strait between Java and Sumatra islands. Hundreds lost their lives, and more than 14,000 were reported injured. Back in Aceh, one local government relocated hundreds of people who once lived in obliterated Kampung Baro village.

But some residents opted to stay put, despite the risks.

“Relocation would mean another wound for us,” said tsunami survivor and fisherman Muhammad Saleh.

“Moving away from the sea would be like a wound on top of a wound because our life depends on the sea.”

The disaster, however, helped to heal some old wounds.

Less than a year after the tsunami, Aceh’s separatist rebels and the Indonesian government agreed to end almost 30 years of bloodshed in a peace deal that gave the region more autonomy.

Thousands are expected to gather Thursday in Banda Aceh, which now has a dedicated tsunami memorial museum.

The day will bring back haunting memories for survivors like Abdul Hadi Firsawan, who wishes he could somehow be reunited with his mother, father and two siblings — all missing and presumed dead.

“I still pray that I could see my parents again, but it’s been 15 years,” he said, adding: “If that’s no longer a reality then I’m sure I’ll meet them in heaven.”

Has the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) changed under the leadership of Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌)? In tone and messaging, it obviously has, but this is largely driven by events over the past year. How much is surface noise, and how much is substance? How differently party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) would have handled these events is impossible to determine because the biggest event was Ko’s own arrest on multiple corruption charges and being jailed incommunicado. To understand the similarities and differences that may be evolving in the Huang era, we must first understand Ko’s TPP. ELECTORAL STRATEGY The party’s strategy under Ko was

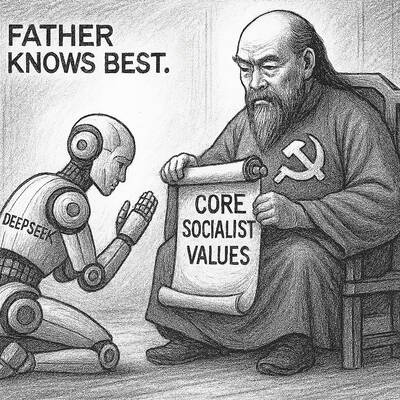

It’s Aug. 8, Father’s Day in Taiwan. I asked a Chinese chatbot a simple question: “How is Father’s Day celebrated in Taiwan and China?” The answer was as ideological as it was unexpected. The AI said Taiwan is “a region” (地區) and “a province of China” (中國的省份). It then adopted the collective pronoun “we” to praise the holiday in the voice of the “Chinese government,” saying Father’s Day aligns with “core socialist values” of the “Chinese nation.” The chatbot was DeepSeek, the fastest growing app ever to reach 100 million users (in seven days!) and one of the world’s most advanced and

It turns out many Americans aren’t great at identifying which personal decisions contribute most to climate change. A study recently published by the National Academy of Sciences found that when asked to rank actions, such as swapping a car that uses gasoline for an electric one, carpooling or reducing food waste, participants weren’t very accurate when assessing how much those actions contributed to climate change, which is caused mostly by the release of greenhouse gases that happen when fuels like gasoline, oil and coal are burned. “People over-assign impact to actually pretty low-impact actions such as recycling, and underestimate the actual carbon

An internal Meta Platforms document detailing policies on chatbot behavior has permitted the company’s artificial intelligence creations to “engage a child in conversations that are romantic or sensual,” generate false medical information and help users argue that Black people are “dumber than white people.” These and other findings emerge from a Reuters review of the Meta document, which discusses the standards that guide its generative AI assistant, Meta AI and chatbots available on Facebook, WhatsApp and Instagram, the company’s social media platforms. Meta confirmed the document’s authenticity, but said that after receiving questions earlier this month, the company removed portions which stated