Dec. 23 to Dec. 29

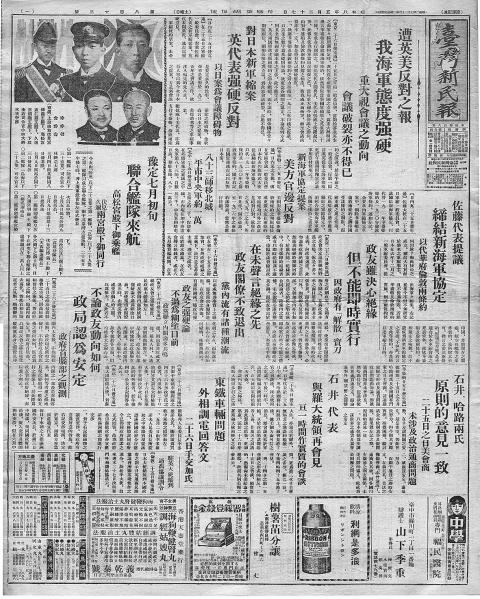

Wu San-lien (吳三連) made his last stand against the Japanese authorities in 1939 when he published and distributed a book criticizing its unfavorable rice policy.

The resistance movement in Taiwan was shut down by then as the Japanese tightened control over the colony after the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937. Wu, who was running the Tokyo bureau of Taiwan New Minpao (台灣新民報), agreed to take on the issue. He had a history of causing trouble for the Japanese, and writes in his memoir, “I don’t own any farmland. But for the righteousness of my people, I gave my all for the farmers of Taiwan. This was my most meaningful and proudest moment.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Wu felt something was wrong, however, when he was fired and recalled to Taiwan. Instead of heading home, he fled to China.

Born into poverty in rural Tainan in 1899 and not entering first grade until the age of 13, Wu’s personal journey is quite remarkable as he was involved in significant events in Taiwan’s history throughout his life.

LIFE OF DEFIANCE

Photo courtesy of Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology

Given his family circumstances, Wu was lucky to have finished secondary school. He insisted on studying in Japan despite fierce objection from his family, who desperately needed money.

“To this day, I don’t know where my determination came from,” he writes, getting his wish through a scholarship from the wealthy Banciao Lin Family (板橋林家).

During his time in Japan, he joined the anti-colonial resistance and was put on a government blacklist for making anti-Japanese speeches across Taiwan on behalf of the Taiwan Cultural Association (台灣文化協會) in 1923. He graduated from business college in 1925 and joined the Osaka Daily News.

Photo courtesy of National Museum of Taiwan Literature

“I realized that there was little racial discrimination in the journalism field, and the thinking was more liberal too,” he writes.

Wu remained in Japan for seven years before returning home to help out at Taiwan New Minpo, which was the first Taiwanese-run daily newspaper in the colony. Wu was the only one among the anti-colonial activists who had any journalism experience, and took on four jobs including managing editor. He recalls that when the authorities blacked out parts of the newspaper they didn’t like, the paper would print the pages with the redacted marks to demonstrate to the readers the lack of freedom of speech and “incite their anti-Japanese sentiments.”

Wu was still in self-exile when the Japanese surrendered in August 1945. He writes that he had three wishes — to witness the Republic of China flag replace the Japanese one atop the Governor General’s Office, to hear the Japanese apologize for their mistreatment of Taiwanese and to build a new Taiwan by Taiwanese hands.

He ended up staying in China for an extra year trying to save Taiwanese who worked for the Japanese during the war and were branded by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) as hanjian (漢奸, traitors to Han Chinese). During this year, he had already heard about the government’s misrule in Taiwan, and had no illusions when he set out for Taiwan at the end of 1946.

INDEPENDENT POLITICIAN

In hope of changing things, Wu ran for the National Assembly, earning a seat as the top vote-getter in Taiwan. This was the body that would be known as the “Ten-thousand year congress (萬年國會),” as they remained in place for the next 44 years due to the KMT’s wartime provisions.

In 1950, KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) personally appointed Wu as mayor of Taipei despite him never joining the party. Wu recalls that he didn’t accomplish much as most of his time was spent dealing with the massive influx of refugees and soldiers from China. The city was in chaos, with illegal settlements sprouted up everywhere and the streets strewn with garbage and human excrement due to the lack of flushable toilets. Space was so lacking that people dug up Japanese cemeteries and even erected structures on the streets.

Despite significant public criticism, Wu became Taipei’s first elected mayor in 1951. His next stint was in the Taiwanese Provincial Assembly, where he was known as one of the famed “Five Dragons and One Phoenix” group of non-KMT politicians who did not hesitate to speak out against the government and pushed for Taiwanese autonomy and democracy.

In 1960, Wu was involved in another significant event — Lei Chen’s (雷震) failed attempt to form an opposition party. Wu was urged to help lead the party, but he distanced himself from the movement out of concern for his business interests and family. Plus, he saw that clashing directly with the KMT was futile.

Lei was soon arrested and thrown in jail for 10 years.

At this point, Wu quit politics and focused on building his business and running the Independent Evening Post (自立晚報). He cofounded three schools, including Taipei Private Yan Ping High School, and set up the Wu San Lien Awards to support local writers and artists. His foundation invited Nobel Prize-winning, anti-communist author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn to Taiwan in 1982, causing a massive media frenzy.

The late historian Chang Yan-hsien (張炎憲) writes that Wu was one of the few people who were trusted by both the KMT and the opposition during the rise of the latter in the 1970s. When pro-democracy protesters clashed with the police in the Kaohsiung Incident of 1979, Chang writes that Wu urged then-president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) to excise restraint and not turn it into another 228 Incident, a 1947 uprising that was brutally suppressed.

Two years after Wu’s death on Dec. 29, 1988, his descendants, along with historians and academics, established the Wu San Lien Foundation for Taiwan Historical Materials (吳三連台灣史料基金會), which has printed a number of invaluable historical books, especially focusing on the 228 Incident and Taiwan’s struggle for democracy. Anyone who has done research on Taiwan’s past should have come across his name at one point.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

The Taipei Times last week reported that the rising share of seniors in the population is reshaping the nation’s housing markets. According to data from the Ministry of the Interior, about 850,000 residences were occupied by elderly people in the first quarter, including 655,000 that housed only one resident. H&B Realty chief researcher Jessica Hsu (徐佳馨), quoted in the article, said that there is rising demand for elderly-friendly housing, including units with elevators, barrier-free layouts and proximity to healthcare services. Hsu and others cited in the article highlighted the changing family residential dynamics, as children no longer live with parents,

It is jarring how differently Taiwan’s politics is portrayed in the international press compared to the local Chinese-language press. Viewed from abroad, Taiwan is seen as a geopolitical hotspot, or “The Most Dangerous Place on Earth,” as the Economist once blazoned across their cover. Meanwhile, tasked with facing down those existential threats, Taiwan’s leaders are dying their hair pink. These include former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), Vice President Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and Kaohsiung Mayor Chen Chi-mai (陳其邁), among others. They are demonstrating what big fans they are of South Korean K-pop sensations Blackpink ahead of their concerts this weekend in Kaohsiung.

Taiwan is one of the world’s greatest per-capita consumers of seafood. Whereas the average human is thought to eat around 20kg of seafood per year, each Taiwanese gets through 27kg to 35kg of ocean delicacies annually, depending on which source you find most credible. Given the ubiquity of dishes like oyster omelet (蚵仔煎) and milkfish soup (虱目魚湯), the higher estimate may well be correct. By global standards, let alone local consumption patterns, I’m not much of a seafood fan. It’s not just a matter of taste, although that’s part of it. What I’ve read about the environmental impact of the

Oct 20 to Oct 26 After a day of fighting, the Japanese Army’s Second Division was resting when a curious delegation of two Scotsmen and 19 Taiwanese approached their camp. It was Oct. 20, 1895, and the troops had reached Taiye Village (太爺庄) in today’s Hunei District (湖內), Kaohsiung, just 10km away from their final target of Tainan. Led by Presbyterian missionaries Thomas Barclay and Duncan Ferguson, the group informed the Japanese that resistance leader Liu Yung-fu (劉永福) had fled to China the previous night, leaving his Black Flag Army fighters behind and the city in chaos. On behalf of the