Dec 9 to Dec 15

As Formosa magazine (美麗島雜誌) celebrated its launch on Sept. 8, 1979 at the Mandarina Crown Hotel (中泰賓館), members and supporters of Ji Feng magazine (疾風雜誌) gathered outside.

The two publications were naturally at odds with each other — Formosa was the mouthpiece of the dangwai (黨外), or politicians who opposed the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) one-party rule, while Ji Feng was founded to counter the opposition, whom it called “Taiwanese independence mobsters (台灣獨立黑拳幫).”

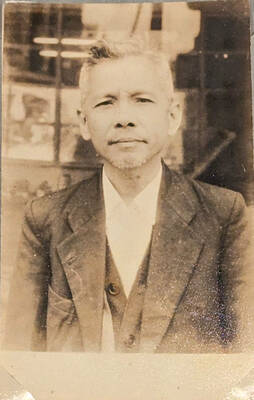

Photo courtesy of Chen Po-wen

The official reason for Ji Feng’s gathering was to denounce the “traitor” Chen Wan-chen (陳婉真), who supported the dangwai from the US after being blacklisted from Taiwan for her political activities. Bringing a contingent of high school students, they yelled patriotic slogans and tried to block people from entering and leaving the hotel. Although there were skirmishes, the Mandarina Crown Hotel Incident did not descend into chaos — that would come three months later.

This event was just one of many conflicts that culminated in the Kaohsiung Incident, or Formosa Incident, on Dec. 10, 1979, when police and protesters clashed during a pro-democracy rally organized by Formosa magazine.

Much has been written about the incident and its ramifications, but everything began a year earlier, when the US announced that it would break relations with Taiwan for China.

Photo: Chu Pei-hsiung, Taipei Times

SIMMERING TENSIONS

Having made significant political gains in the local elections of 1977 — despite accusations that the KMT rigged votes — the dangwai was hoping to further its success during the supplementary elections for the national assembly and legislature.

Since opposition political parties were banned, these independent candidates formed a dangwai canvassing team in October 1978 to campaign as a group, which alarmed the government. Their collective platform included ending martial law, government censorship, the ban on new political parties and discrimination against local languages, and calling for the release of political prisoners.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The first incident broke out on Dec. 6 during a dangwai press conference, when then-legislator Huang Hsin-chieh (黃信介) changed a phrase in the national anthem from “my party” to “my people,” causing pro-KMT politicians to rush the stage.

When the US announced that it was breaking relations with Taiwan for China on Dec. 16, just six days before the vote, the government suspended the elections. They issued several warnings that any pro-independence or anti-government activities would be severely punished. But on Dec. 25, the dangwai released a public statement criticizing the KMT’s authoritarian rule and reiterating its previous demands for democracy and freedom.

A month later, the government arrested dangwai leader Yu Teng-fa (余登發), tying him and his son to a sedition case and sentencing them to eight and two years in jail respectively. Led by then-Taoyuan County Commissioner Hsu Hsin-liang (許信良), the dangwai took to the streets for the first time to call for Yu’s release. The government then shut down two dangwai publications and moved to impeach Hsu for his actions.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The dangwai continued to organize gatherings throughout 1979, but in July, the government started suppressing them by force. On Aug. 4, the police shut down the underground newspaper Chao Liu (潮流) and arrested two of its staff in a widely-publicized incident after co-founder Chen, the dangwai supporter, protested by staging a hunger strike at Taiwan’s representative office in New York.

OPPOSING MAGAZINES

Ji Feng was founded on July 7, 1979. It slams the dangwai in its introductory statement.

“What makes us infinitely angry is that while Taiwan, Kinmen and Matsu have achieved peace and prosperity never seen in thousands of years of Chinese history… there’s a tiny countercurrent — the aspirant Taiwanese independence mobsters. They are driven by power and desire, and walk the same road as the communist bandits. They have willingly oppressed China on behalf of Westerners, using ‘democracy and human rights’ as a guise to incite violence and divide our territory and destroy our glorious achievements on this base to reclaim China… Our compatriots, it is time for the silent majority to attack these bandits! Let us unite and strike relentlessly and viciously against these demons!”

Formosa released its first edition on Aug. 16, 1979. Huang, the legislator, writes in the introduction: “Faced with national fervor toward the elections, the KMT panicked due to its political crisis [with the US]. It hurriedly stopped the elections and has been using all sorts of high-pressure tactics to destroy this tide of democracy, causing much worry and uncertainty in society over the past half-year… But democracy will not die. Long live the elections! We are encouraged by the people’s passion to participate in politics, and strongly believe that democracy is the tide of the times and cannot be stopped! This is why we have determinedly founded Formosa magazine to push forward the political movement of the new generation!”

In its third issue, the Ji Feng camp called their actions at the Mandarina Crown Hotel a “large-scale and far-reaching patriotic movement to save the country,” vowing that they would continue to take action until the “independence mobsters” were stopped.

Despite this vow, Ji Feng denied involvement when Formosa’s office and Huang’s home were ransacked by unknown attackers. Instead, they claimed that Formosa staff orchestrated the attacks themselves to gain sympathy and make the KMT look bad, in order to justify their “rebellious actions.”

In its sixth issue, Ji Feng celebrated the Kaohsiung Incident, stating: “The night of Dec. 10 is when god willed the utter destruction of these independence mobsters.”

Little would they know that today, the incident is now remembered as the turning point in Taiwan’s struggle for democracy.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Francis William White, an Englishman who late in the 1860s served as Commissioner of the Imperial Customs Service in Tainan, published the tale of a jaunt he took one winter in 1868: A visit to the interior of south Formosa (1870). White’s journey took him into the mountains, where he mused on the difficult terrain and the ease with which his little group could be ambushed in the crags and dense vegetation. At one point he stays at the house of a local near a stream on the border of indigenous territory: “Their matchlocks, which were kept in excellent order,

Jan. 19 to Jan. 25 In 1933, an all-star team of musicians and lyricists began shaping a new sound. The person who brought them together was Chen Chun-yu (陳君玉), head of Columbia Records’ arts department. Tasked with creating Taiwanese “pop music,” they released hit after hit that year, with Chen contributing lyrics to several of the songs himself. Many figures from that group, including composer Teng Yu-hsien (鄧雨賢), vocalist Chun-chun (純純, Sun-sun in Taiwanese) and lyricist Lee Lin-chiu (李臨秋) remain well-known today, particularly for the famous classic Longing for the Spring Breeze (望春風). Chen, however, is not a name

There is no question that Tyrannosaurus rex got big. In fact, this fearsome dinosaur may have been Earth’s most massive land predator of all time. But the question of how quickly T. rex achieved its maximum size has been a matter of debate. A new study examining bone tissue microstructure in the leg bones of 17 fossil specimens concludes that Tyrannosaurus took about 40 years to reach its maximum size of roughly 8 tons, some 15 years more than previously estimated. As part of the study, the researchers identified previously unknown growth marks in these bones that could be seen only