Bebo Haider’s beauty parlour is bright, small, and decorated sparsely with three large photographs: transgender models who became her clients because the Karachi salon is one of the few in Pakistan which caters to them without judgement.

Tarawah, in a middle-class neighbourhood of the sprawling southern port city, is owned and run by Haider, herself a transgender person who came to Karachi in 2003 from a small rural town in southern Sindh province with dreams of becoming a beautician.

It was not easy. Even when the owner of one salon in a posh Karachi neighborhood finally decided to take a chance on her, the clients refused her services — or to return her greetings, she said. It took two years before one salon regular finally returned her hello, she said — but the thaw, for that customer at least, was complete.

Photo: AFP

“After that day she would not get her hair and make up done by anybody else at the parlour,” Haider said jubilantly, sitting in her hairdressing chair. “Good manners win the world.”

Transgenders — also known in Pakistan as khawajasiras, an umbrella term denoting a third sex that includes transvestites and eunuchs — have long fought for their rights in the deeply patriarchal and conservative country.

Organized and politically active, in many respects they have made impressive gains.

In 2009 Pakistan became one of the first countries in the world to legally recognise a third sex. Last year, Pakistan’s parliament passed a historic bill providing transgender people with the right to determine their own gender identity in all official documents, including choosing a blend of both genders.

A Pakistani TV channel put the country’s first transgender news anchor on air in 2018, while several have also run in elections. But — despite these gains — many still live daily as pariahs, often reduced to begging and prostitution, subjected to extortion and discrimination or targeted for violence. Haider fought hard to avoid that fate. Once she gained a foothold with her first job, she began to grow politically active, joining transgender rights organizations and eventually becoming the president of Sabrang, one community group.

When a Dutch organization said it wanted to finance a project to empower the transgender community, she and a partner jumped on the chance to open their own salon — which, they say, is the first transgender owned and run beauty salon in Pakistan.

“I never looked back,” Haider said.

SYMBOL OF EMPOWERMENT

Transgenders are often judged, harassed or even denied entry at other salons, she and her customers said.

“When we would sit along the ladies at the parlour, they would feel nervous, confused and even feel repulsive of us. [But] we are also human beings,” said Mahi Doll, a 21-year client of Tarawah.

Haider’s salon, Doll says, is more than just a safe space for her customers to get their hair and make-up done.

“This is a symbol of transgender empowerment,” she said. The salon is inside a crowded market, surrounded by grocery and milk shops. When Haider first opened it, she said, neighbors were so hostile that she felt afraid. “I would wear tough looks when I came to the shop so that people would not dare to mess with me,” she said.

She warned her clients to dress conservatively, and deployed the strategy which had worked so well before: good manners.

It worked.

“Whenever she sees us, she greets us with a good heart and she meets with everybody pleasantly,” said Mohammad Akram, the 40-year-old owner of a milk shop next to the salon.

“We are not concerned with what their gender is,” he added.

‘DO I LOOK GOOD?’

Many modern-day transgender people in Pakistan claim to be cultural heirs of the eunuchs who thrived at the courts of the Mughal emperors that ruled the Indian subcontinent for two centuries, until the British arrived in the 19th century and banned them.

Today, people who identify as transgender number at least half a million in Pakistan, according to several studies — possibly up to two million, say TransAction, a rights organization. Haider and other activists helping her hope the salon is just the first step on the road to economic empowerment for their community. “Awareness has started to spread now among the people that we can do (respectable) works also,” Haider said, describing initiatives such as her salon as a “practical way” of normalizing transgenders in Pakistan.

During AFP’s visit to Tarawah, client Mahi Doll perched in a black reclining chair to have her hair shampooed and treated, then a manicure.

Haider then began doing Doll’s make-up, lining her eyes darkly to match Haider’s own. “The eye makeup is the essence,” she explained.

After finishing Doll’s eyes, Haider turned back to her own reflection, reviewing herself in the mirror.

“Do I look good?” she said softly, apparently to herself. “I am beautiful. Am I not?”

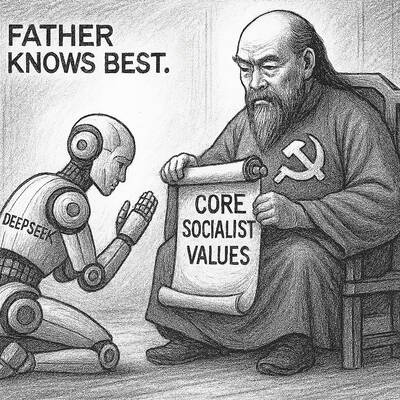

It’s Aug. 8, Father’s Day in Taiwan. I asked a Chinese chatbot a simple question: “How is Father’s Day celebrated in Taiwan and China?” The answer was as ideological as it was unexpected. The AI said Taiwan is “a region” (地區) and “a province of China” (中國的省份). It then adopted the collective pronoun “we” to praise the holiday in the voice of the “Chinese government,” saying Father’s Day aligns with “core socialist values” of the “Chinese nation.” The chatbot was DeepSeek, the fastest growing app ever to reach 100 million users (in seven days!) and one of the world’s most advanced and

Has the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) changed under the leadership of Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌)? In tone and messaging, it obviously has, but this is largely driven by events over the past year. How much is surface noise, and how much is substance? How differently party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) would have handled these events is impossible to determine because the biggest event was Ko’s own arrest on multiple corruption charges and being jailed incommunicado. To understand the similarities and differences that may be evolving in the Huang era, we must first understand Ko’s TPP. ELECTORAL STRATEGY The party’s strategy under Ko was

The latest edition of the Japan-Taiwan Fruit Festival took place in Kaohsiung on July 26 and 27. During the weekend, the dockside in front of the iconic Music Center was full of food stalls, and a stage welcomed performers. After the French-themed festival earlier in the summer, this is another example of Kaohsiung’s efforts to make the city more international. The event was originally initiated by the Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association in 2022. The goal was “to commemorate [the association’s] 50th anniversary and further strengthen the longstanding friendship between Japan and Taiwan,” says Kaohsiung Director-General of International Affairs Chang Yen-ching (張硯卿). “The first two editions

It was Christmas Eve 2024 and 19-year-old Chloe Cheung was lying in bed at home in Leeds when she found out the Chinese authorities had put a bounty on her head. As she scrolled through Instagram looking at festive songs, a stream of messages from old school friends started coming into her phone. Look at the news, they told her. Media outlets across east Asia were reporting that Cheung, who had just finished her A-levels, had been declared a threat to national security by officials in Hong Kong. There was an offer of HK$1m (NT$3.81 million) to anyone who could assist