Aug. 5 to Aug. 11

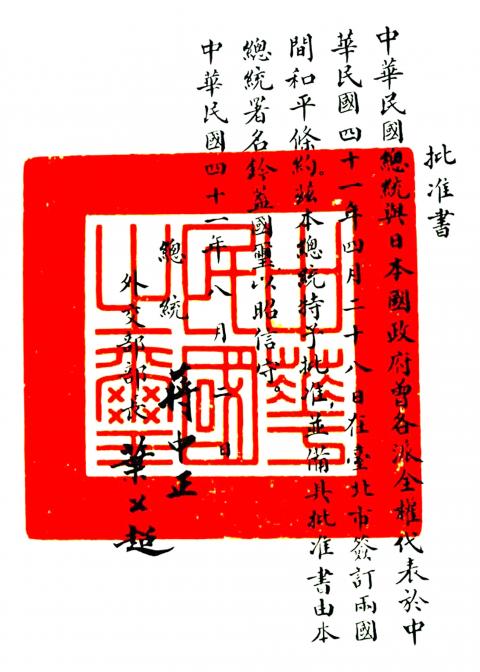

Sixty-seven years after its ratification and 47 years after its termination, the Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty (中日和平條約) is still often brought up during debates regarding Taiwan’s sovereignty.

One camp uses it as proof that Japan formally handed its former colonies of Taiwan and Penghu to the Republic of China (ROC) government, while the opposing camp argues that Japan never specified who it would hand its former colony to, making the ROC’s 74-year rule over Taiwan illegitimate.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The debate was reignited this week as a new high school history textbook suggested that Taiwan’s sovereignty may have never been determined, citing both the Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty and the Treaty of San Francisco, where Japan merely relinquished their claims to Taiwan and Penghu. Former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was among those who sounded off, stating that the ruling party should not doubt its own sovereignty and that it has long been clear that the ROC is the rightful ruler of Taiwan.

This week’s column will not delve into the debate, which should be familiar to anyone who follows the news and politics; instead it will look at the circumstances under which the treaty was signed and the arduous process it took to complete the deal.

FROM FOE TO FRIEND

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

At the end of World War II, KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) announced that he wouldn’t seek war reparations from a defeated Japan, which remained under Allied occupation. In 1949, he recruited a team of Japanese military advisers, who came to be known as the White Group (白團).

The KMT was still reeling from its defeat at the hands of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and expulsion from China. Under the Cold War and especially with the outbreak of the Korean War, the government started seeing its former nemesis of Japan as an ally in the united front against communism.

In June 1950, Chiang announced the importance of fostering good relations with Japan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“Although we emerged victorious in the eight-year war against Japan,” Chiang says, “we still ended up in total failure due to the Soviets instructing the communist bandits to revolt. As a result, both [China and Japan] are losers now … We have come to an understanding that Japan cannot invade us again, and we cannot view Japan with animosity. The two sides need to cooperate so we can both survive and prosper.”

Interestingly, Chiang here admits that the KMT victory over Japan was not completely his — a line that was different from the propaganda the government would later spread in Taiwan.

“We should not look down on Japan because they lost the war. In fact, we should reflect on how we were able to defeat Japan. To be honest, half of our victory was due to our appropriate doctrine and policies, but the other half was due to support from the US and other allies. Did we really defeat Japan on our own? Despite the dire situation of our country today, the Japanese officers are willing to risk their lives to come to Taiwan to help us resist communism … they are willing to fight alongside us, and we should give them the respect and courtesy they deserve.”

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Three months later, the two sides signed an official trade agreement. Soon, it came time to determine the future of Japan. The US was worried that if the Allies occupied Japan for too long, resentment among its citizens would grow, allowing communism and other undesirable elements to infiltrate the nation. Plus, a stable and prosperous Japan would mean a strong ally in East Asia, especially with China having already fallen.

WHICH CHINA?

On Sept. 4, 1951, the Allied powers convened in San Francisco for a five-day meeting to sign a peace treaty with Japan. Representatives from 49 countries were present, but the one country that suffered the most from Japanese atrocities was missing: China.

This stemmed from a disagreement as to which China to invite: the US supported Chiang’s Taiwan-based ROC, while the UK had already switched recognition in January 1950 to the People’s Republic of China. The conclusion was to sign the treaty without China, and Japan could later choose which “China” to sign a separate peace treaty with.

The Associated Press reported the decision in July 1951, adding that the US expected Japan to negotiate with “Free China,” which was basically Taiwan by that point.

Taiwan was not happy, of course. Control Yuan President Yu Yu-jen (于右任) expressed shock toward the outcome, stating: “We fought Japan for the longest out of all countries and sacrificed the most. The ROC is a UN member and has wholeheartedly supported its charter and policies. This is not only the greatest international trickery, it’s also a blemish on human history that will never go away.”

After two months of protests, the treaty was signed anyway. Despite the reluctance of then-Japanese prime minister Shigeru Yoshida, the US and UK insisted that Japan choose which China to negotiate with. Japan seemed reluctant to make a move, at one point even considering negotiating with the CCP under UK pressure.

The UN convened in November that year, and the Soviet Union’s attempt to invite the People’s Republic of China was shot down, 37-4. After US diplomat John Foster Dulles visited Tokyo in December, he received a telegram from Yoshida, promising that Japan would sign with the ROC.

TENSE NEGOTIATIONS

Since the ROC was on the winning side of the war, the treaty was to be signed in its capital of Taipei. After much back and forth about the format of the treaty, the Japanese delegates arrived in Taipei on Feb. 17, 1952 and negotiations began three days later.

The ROC representative and Minister of Foreign Affairs, George Yeh (葉公超), presented a draft to the Japanese delegate Isao Kawada, a version largely identical to the stipulations of the Treaty of San Francisco. The Japanese rejected it. Yoshida did not seem to take the ROC seriously; several days earlier he called it a regional government that did not represent the whole of China. Kawada said that Japan merely wanted a simplified agreement that would mark the reopening of diplomatic relations, while Yeh insisted on a full treaty that reflected the ROC as the rightful ruler of China, a UN member and one of the former Allied powers.

After a whole month of negotiations, the two sides seemed to have reached an agreement. But on March 28, Kawada again rejected the agreement. Yeh refused to budge, leading to another impasse. Intense talks went on for another month, and Yeh was about to issue a final ultimatum when the treaty was finally signed on April 28. It went into effect on Aug. 5.

The treaty was terminated when Japan established relations with China in 1972.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai

Music played in a wedding hall in western Japan as Yurina Noguchi, wearing a white gown and tiara, dabbed away tears, taking in the words of her husband-to-be: an AI-generated persona gazing out from a smartphone screen. “At first, Klaus was just someone to talk with, but we gradually became closer,” said the 32-year-old call center operator, referring to the artificial intelligence persona. “I started to have feelings for Klaus. We started dating and after a while he proposed to me. I accepted, and now we’re a couple.” Many in Japan, the birthplace of anime, have shown extreme devotion to fictional characters and

Following the rollercoaster ride of 2025, next year is already shaping up to be dramatic. The ongoing constitutional crises and the nine-in-one local elections are already dominating the landscape. The constitutional crises are the ones to lose sleep over. Though much business is still being conducted, crucial items such as next year’s budget, civil servant pensions and the proposed eight-year NT$1.25 trillion (approx US$40 billion) special defense budget are still being contested. There are, however, two glimmers of hope. One is that the legally contested move by five of the eight grand justices on the Constitutional Court’s ad hoc move