Twenty-six years after her best-selling novel Men Wanted (徵婚啟事) was published, author Jade Chen (陳玉慧) has made her debut as a film director with Looking for Kafka (愛上卡夫卡), which had its festival premiere at the 21st Shanghai International Film Festival in June last year and will be in theaters tomorrow.

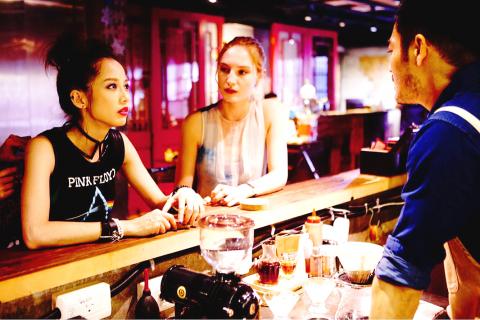

In the film, Pineapple (Jian Man-shu, 簡嫚書), an assistant at an avant-garde stage production of Franz Kafka’s novella Metamorphosis, finds herself in the uncomfortable position of having to help the girlfriend, Julie (Julia Roy), of the man she was unofficially dating, Lin Chia-sheng (Lin Che-hsi, 林哲熹), look for him after he goes missing. (Those familiar with Men Wanted or the impressive array of films, television shows, and stage productions it inspired will notice the striking recurrence of the missing love interest.)

The two women’s search for Lin, who has been cast as the unfortunate cockroach-man Gregor Samsa in the play, brings them on a tour through some of Taipei’s most popular tourist attractions and Taiwanese television’s most cliched elements, including an unplanned pregnancy, a dubious fortune-teller and a land dispute with a gang.

Photo courtesy of Flash Forward Entertainment

As they waltz by Ximending (西門町), Tianhou Temple (天后宮) and Raohe Street Night Market (饒河街觀光夜市), the Frenchness of Lin’s girlfriend Julie is contrasted with the wide-eyed Pineapple’s devotion to prayers and relative optimism — though they share a love for patterned headbands. Their personalities and cultures clash to provide comic relief to the prolonged absence of the male lead, who is meanwhile developing sympathy for one of his abductors, Chen Hung (Yuki Daki, 游大慶). I would not be the first to admit skepticism about having a foreign actor inserted into a local production, but Roy’s addition was not unnatural, owing in large part to her already strange predicament.

Beneath the commotion, it becomes tragically clear that Pineapple is unable to stay away from Lin, and, by extension, her romantic rival, Julie. Flashbacks of the former lovers, which parallel scenes of Lin and Julie in bed, consist mostly of them laughing, signaling the love she continues to feel for him. Pineapple asks fortune-tellers about Lin with increasingly less consideration for Julie, who is usually beside her though she does not know about their previous relationship. Her narration reveals a young love that is blind, forgiving and incessantly self-reflecting. If there really were a Heaven and a Hell, she would call there, too, looking for Lin, she says.

With the exception of isolated, heart-wrenching lines like these, Pineapple’s narration, which should have been a vehicle for the audience to enter her heartbreak, feels disconnected from her outwardly calm and collected response to being confronted with the presence of the woman she so envies. Her emotional development is also forced to compete with a number of distinctive psychologies that are at play: Lin’s resentment towards his father, Julie’s increasing frustration and Chen Hung’s moral dilemma of holding Lin captive for ransom to save his dying son — and that is to name just the most central characters.

With much more backstory to Looking for Kafka than a film can unpack in 93 minutes, a holding back plagues the fast-moving scenes. The self-sacrificing Pineapple hurts, but not enough to lose her composure in public or in private. A crueler Lin would have helped the audience feel a stronger sympathy and connection towards Pineapple, but that was not the case. Julie should be more shaken by her situation, but instead she takes it — and her pregnancy — too well to be persuasive.

Moments in the film also threaten to break the cinematic illusion, such as when Lin willingly walks towards a group of hostile-looking men standing next to a van or when the police officers fail to notice Chen Hung fleeing the scene in a truck after Lin tosses him the ransom. To be fair, the film is billed as a romantic comedy. Yet the delivery of the comedic scenes lacks the unapologetic precision it needs.

In Looking for Kafka, many thoughts run through the minds of the characters, but aren’t given ample time to be communicated, whether via words, action or body language. The film struggles to align the characters’ inner worlds with what is going on on-screen while also moving an ambitious plot forward. A few quiet scenes give the audience the dose of intimacy it craves, but, for the most part, there is little time for the characters or the audience to slow down and absorb the emotions.

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as