Dec. 24 to Dec. 30

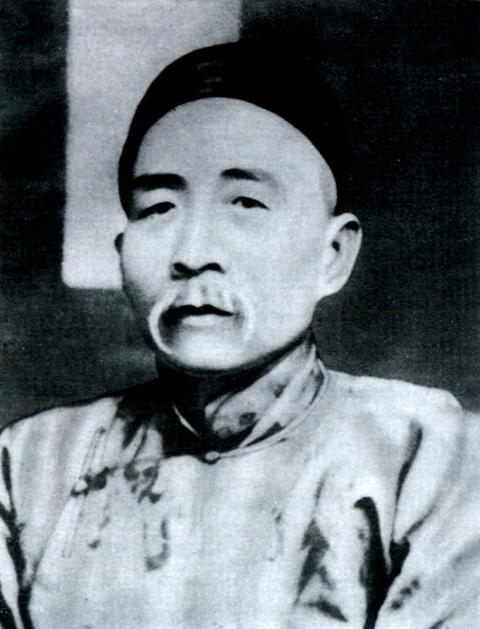

History can be convoluted: Chiu Feng-chia (丘逢甲), vice-president of the short-lived Republic of Formosa (台灣民主國), fled across the Taiwan Strait in 1895 and helped create the Republic of China (ROC), whose government ended up fleeing to Chiu’s homeland of Taiwan in 1949.

And even though Chiu secretly left Taiwan shortly after the Japanese occupying forces easily took Keelung in May 1895, Taichung’s Fengchia University is named after him as an “anti-Japanese hero.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Many in Taiwan see him as a deserter, and Lien Heng’s (連橫) General History of Taiwan (台灣通史) even alleges that Chiu looted public funds before he left, contrasting him with Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興) and Hsu Hsiang (徐驤), both of whom fought the Japanese to the death.

Those who favor him call him a “patriotic poet” (愛國詩人) who fled Taiwan in regret after organizing the Republic of Formosa and putting up a futile resistance. He spent the rest of his life writing mournful poems lamenting the loss of Taiwan, and named his firstborn son Chiu Nien-tai (丘念台, literally “missing Taiwan”).

Not only does this controversial figure have a university named after him, there’s also the Chiu Feng-chia Memorial Park in Taichung and a commemorative stele at Maolishan Park (貓裏山) in his home county of Miaoli.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

REFUSING TO YIELD

First of all, the book Collections of Essays on Taiwanese History Records(台灣史志論叢) by historian Huang Hsiu-cheng (黃秀政) states that due to the chaotic circumstances, no concrete records were left behind regarding whether Chiu really took the money when he left, making it an issue not worth debating. What really matters is his legacy, Huang writes.

Chiu was born on Dec. 26, 1864 in Miaoli, when Taiwan was part of the Qing Empire. A gifted child, he became an imperial scholar at the age of 14 and passed the highest level of imperial examinations in Beijing in 1889. However, he soon returned to Taiwan, preferring to be an educator rather than serve at the Qing court, which was in disarray and would collapse two decades later.

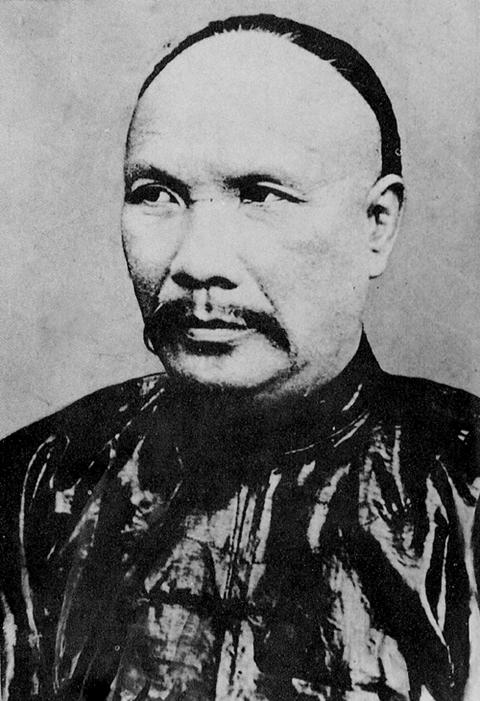

A portrait of Tang Ching-sung, president of the short-lived Republic of Formosa.

While Taiwan was not involved in the Sino-Japanese war of 1894, Chiu felt uneasy, telling a friend: “Turbulent times are coming. The Japanese are burning with ambition, and they’ve drooled over this place (Taiwan) for a long time.”

He was right — the Qing ceded Chiu’s homeland to the Japanese victors in the Treaty of Shimonoseki.

Chiu’s actions up to his departure can truly be considered heroic. He traveled the country to recruit a resistance army, reportedly often breaking down in tears at the end of his speeches. He wrote to then-provincial governor Tang Ching-sung (唐景崧) 10 times stating that he would do all he could do defend Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

After the signing of the treaty, Chiu and other members of the Taiwanese elite begged the Qing and other foreign powers to help them, but the Qing decided to sacrifice Taiwan to keep the rest of its territory intact. Imperial tutor Weng Tonghe (翁同龢) writes in his diary: “Each word of the telegram sent by … Chiu Feng-chia was soaked in tears and blood. Reading it has made me felt ashamed to stand in front of my people.”

Having no choice, Chiu and his peers turned to plan B and declared Taiwan an independent Republic of Formosa so that it would no longer be Qing territory, and then to fight off the Japanese. Tang was chosen as president, while Chiu served as vice-president and commander of the resistance troops. The new government was inaugurated on May 25, 1895.

CONFLICTING ACCOUNTS

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

On May 29, the Japanese landed on the north coast, quickly taking Keelung in a matter of days. While it’s known that Tang fled to China a few days later, there are several versions of Chiu’s actions. According to Huang, Tang sent Chiu, who was stationed in today’s Nankan area in Taoyuan City, an urgent telegram requesting his support in the north.

Huang writes that there are conflicting historical accounts as to whether Chiu responded to the call, and whether his army clashed with the Japanese along the way. Even today, each book or study seems to have its own version of events.

The timing of Chiu’s departure is also disputed, ranging from him leaving right after Tang without putting up a fight, to staying and resisting for several weeks. However, after cross-examining the timing of other battles and accounts, Huang concludes that the latest Chiu would have left was around the end of June. Chiu’s name was not mentioned at all by the time Wu Tang-hsing began his own resistance in mid-June, showing that he had already given up fighting by then. Furthermore, Huang writes that he could find no evidence that Chiu was involved in any battle.

Huang writes that Chiu’s biggest contribution was his efforts in rallying people across Taiwan to take up arms and resist the Japanese, and his progressive ideals and knowledge of Western politics helped Tang quickly set up the Republic of Formosa. The problem is that he did not follow the “we shall defend Taiwan together to our deaths” mantra he espoused in his speeches.

In Chiu’s defense, several accounts state that he was determined to stay and fight, but his trusted subordinate convinced him to flee by saying, “Although Taiwan is done for, if you can strengthen the motherland (China), there’s still a chance to reclaim the land and avenge this disgrace.”

LIFE OF REGRET

Chiu penned his first regretful poem right as he left Taiwan: “The chancellor has the power to cede territory, and the lone minister is powerless to reverse the situation. I can only get on a boat like Fan Li (范蠡), and when I look back at my homeland, I feel nothing but immense sadness.”

He would write many poems lamenting this great loss for the rest of his life.

Fan Li was an ancient Chinese minister who left the country of Yue on a boat after helping its king destroy his rival and exact revenge. Ironically, unlike Chiu, Fan actually succeeded in his task.

Interestingly, while Tang was relieved of his posts and lived the rest of his life in shame, Chiu was favored by the Qing, holding many high-level educational positions in Guangzhou before joining the anti-Qing resistance. He was one of the representatives who elected Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) as temporary president of the newly-formed ROC.

Chiu died in 1912, never setting foot in Taiwan again. His son, who left Taiwan as an infant, lived to see the day of Japanese defeat, returning to Taiwan for good in October 1946 as a KMT official.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Jacques Poissant’s suffering stopped the day he asked his daughter if it would be “cowardly to ask to be helped to die.” The retired Canadian insurance adviser was 93, and “was wasting away” after a long battle with prostate cancer. “He no longer had any zest for life,” Josee Poissant said. Last year her mother made the same choice at 96 when she realized she would not be getting out of hospital. She died surrounded by her children and their partners listening to the music she loved. “She was at peace. She sang until she went to sleep.” Josee Poissant remembers it as a beautiful

For many centuries from the medieval to the early modern era, the island port of Hirado on the northwestern tip of Kyushu in Japan was the epicenter of piracy in East Asia. From bases in Hirado the notorious wokou (倭寇) terrorized Korea and China. They raided coastal towns, carrying off people into slavery and looting everything from grain to porcelain to bells in Buddhist temples. Kyushu itself operated a thriving trade with China in sulfur, a necessary ingredient of the gunpowder that powered militaries from Europe to Japan. Over time Hirado developed into a full service stop for pirates. Booty could

Before the last section of the round-the-island railway was electrified, one old blue train still chugged back and forth between Pingtung County’s Fangliao (枋寮) and Taitung (台東) stations once a day. It was so slow, was so hot (it had no air conditioning) and covered such a short distance, that the low fare still failed to attract many riders. This relic of the past was finally retired when the South Link Line was fully electrified on Dec. 23, 2020. A wave of nostalgia surrounded the termination of the Ordinary Train service, as these train carriages had been in use for decades

Lori Sepich smoked for years and sometimes skipped taking her blood pressure medicine. But she never thought she’d have a heart attack. The possibility “just wasn’t registering with me,” said the 64-year-old from Memphis, Tennessee, who suffered two of them 13 years apart. She’s far from alone. More than 60 million women in the US live with cardiovascular disease, which includes heart disease as well as stroke, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. And despite the myth that heart attacks mostly strike men, women are vulnerable too. Overall in the US, 1 in 5 women dies of cardiovascular disease each year, 37,000 of them