What are the three most visited places of worship in Changhua County’s Lukang (鹿港)? That’s easy: The exquisite Longshan Temple (龍山寺), the delightfully timeworn Tianhou Temple (天后宮) and the 21st century, made-of-glass Husheng Temple (護聖宮).

It’s harder to say which of Lukang’s many religious sites is the most intriguing. Even if you ignore their spiritual significance, Longshan and Tianhou temples still deserve their popularity. Husheng Temple isn’t half as impressive, and I’ve always suspected it was conceived to lure people to the adjacent Taiwan Glass Gallery (臺灣玻璃館). That said, when the sun sets, it does have a certain appeal.

MANAGING DISPUTES

Photo: Steven Crook

I visit Lukang at least once a year, because I continue to discover fascinating details about this town of 87,000. Reading Donald R. DeGlopper, an American anthropologist who did field research in the area in the late 1960s, I learned that until World War II, inter-clan tensions were managed in a novel manner.

Menfolk belonging to the town’s three most powerful surname-groups — Huang (黃), Shi (施) and Xu (許) — would, DeGlopper wrote, get together “every year on one day in the early spring, line up by surname, and throw rocks at their fellows of other surnames. They were thus throwing rocks at and dodging rocks thrown by men who were in other contexts their in-laws, mother’s brothers, business partners, old school friends [while] women and children watched and cheered.”

People got hurt, but as far as DeGlopper could ascertain, no one was ever killed. This annual session of violence had an additional function, some believing that, “if blood was not shed in the spring, then the community might suffer bad luck during the coming year.”

Photo: Steven Crook

CENTER OF TRADE, MUSLIM CONNECTION

There was a Muslim presence in the Lukang of yore. The ancestors of Ding Shouquan (丁壽泉), the imperial examination degree holder and senior official, who in 1893 commissioned the construction of Lukang Ding Mansion (鹿港丁家古厝), were undoubtedly Muslims. Back in the village in Quanzhou in Fujian from which Ding Shouquan’s forefathers migrated to Taiwan, members of the same clan are even now classified as the ethnic Hui Muslim minority (回族) by the Chinese government.

For much of the 18th century and a good part of the 19th century, Lukang was second only to Taiwanfu (臺灣府, the name of Tainan throughout much of its history) as a center of trade. It attracted settlers from the coast of Fujian, where tens of thousands of Arab and Persian merchants had been living since the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). Many of them were already partly assimilated into Han society before they relocated to Taiwan. Once on the island, separated from Muslim communities on the Chinese coast, they gradually lost their traditions.

Photo: Steven Crook

Lukang’s Muslim cemetery is long gone, and currently there are no mosques in Changhua County. However, in 1725 a temple devoted to a Chinese god was founded where an Islamic hall of worship had formerly stood.

Beitou Kuocuo Baoan Temple (北頭郭厝保安宮), rebuilt most recently in 1991, is on the corner of Yongfeng Road (永豐路) and Siwei Road (四維路), less than 300m north of Tianhou Temple.

As the toponym implies, this neighborhood was once a stronghold of folk surnamed Kuo (郭). It seems Kuo clansmen were responsible for both establishing the mosque and, a few generations later, repurposing it into a shrine where local popular religion was practiced.

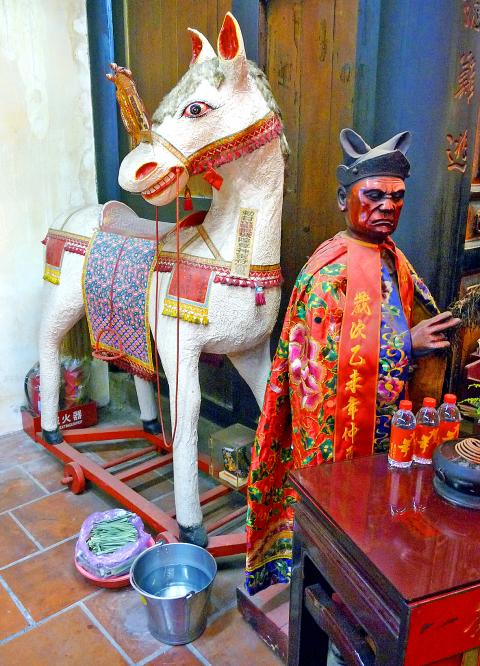

Photo courtesy of A. Synaptic

The temple’s name led me to assume it was dedicated to Baosheng Dadi (保生大帝), the medicine deity worshipped at Taipei’s Dalongdong Baoan Temple (大龍峒保安宮). But when I reached the shrine, I couldn’t find that god anywhere.

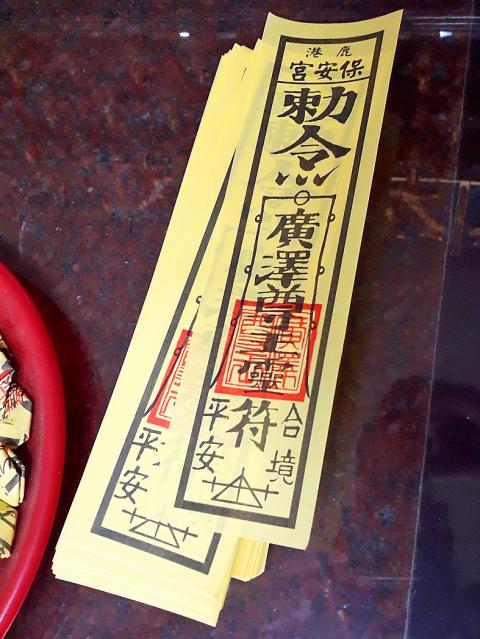

A local appeared, and he told me the main deity enshrined here is King Kuangtzu (廣澤尊王). The Chinese-language Wikipedia page for this god lists seven alternative names: Three begin with the character for Kuo, while two start with Baoan (保安).

King Kuangtzu is the deification of a Quanzhou native who lived in the 10th century and died before his 16th birthday. But I wasn’t as interested in his biography as something else I’d read about the temple. The man confirmed that many worshippers, knowing there used to be a mosque here, exclude pork from any offerings they make. After I got home, I read that many Lukang natives surnamed Kuo don’t sacrifice pig flesh to their ancestors, and don’t eat pork during periods of mourning.

Photo: Steven Crook

SPONGEBOB SQUAREPANTS

Those who pray at Baoan Temple preserve a sliver of the town’s distant past. By contrast, the managers of Yuqu Temple (玉渠宮) have shown they’re not afraid to embrace modernity. When this deliciously colorful shrine was updated some years back, it was decided to include depictions of SpongeBob SquarePants, his foil Patrick Star, Mickey Mouse and Doraemon. Each image is no bigger than a child’s hand, and on the highest beam at the very front, so photographing them isn’t easy.

The Nov. 24, 2009 edition of the Liberty Times (the Taipei Times’ sister newspaper) quoted the person in charge of the renovation as saying that the cartoon characters were added because the shrine honors Marshal Tian Du (田都元帥),the god of performers and drama. This deity is also worshipped by many of Taiwan’s Songjiang battle arrays.

Photo: Steven Crook

Another unusual feature of Yuqu Temple is that, instead of stone lion sculptures on either side of the entrance, there’s a dog on the left and a rooster on the right. The temple is at the north end of Chewei Lane (車圍巷), near the No 1 market.

Conventional guardian lions can be seen outside Lukang’s Chenghuang Temple (城隍廟) at 366 Jhongshan Road (中山路). Thick metal cables ensure the lions don’t get stolen — an interesting precaution, because one of the resident deities has an impressive track record for resolving cases of theft.

General Fan’s (范將軍) most acclaimed success came in 1984, when in just five days he cracked a high-profile case after police had spent a month getting nowhere. He may be a superb detective, but if the way the stone lions are fixed to the ground means anything, he can’t be much of a security guard.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture, and business in Taiwan since 1996. Having recently co-authored A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai, he is now updating Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide.

JUNE 30 to JULY 6 After being routed by the Japanese in the bloody battle of Baguashan (八卦山), Hsu Hsiang (徐驤) and a handful of surviving Hakka fighters sped toward Tainan. There, he would meet with Liu Yung-fu (劉永福), leader of the Black Flag Army who had assumed control of the resisting Republic of Formosa after its president and vice-president fled to China. Hsu, who had been fighting non-stop for over two months from Taoyuan to Changhua, was reportedly injured and exhausted. As the story goes, Liu advised that Hsu take shelter in China to recover and regroup, but Hsu steadfastly

Taiwan’s politics is mystifying to many foreign observers. Gosh, that is strange, considering just how logical and straightforward it all is. Let us take a step back and review. Thanks to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), starting this year people will once again have Christmas Day off work. In 2002, the Scrooges in the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) said “bah, humbug” to that. The holiday is not actually Christmas, but rather Constitution Day, celebrating the enactment of the Constitution of the Republic of China (ROC) on December 25, 1947. The DPP and the then pan-blue dominated legislature

Focus Taiwan reported last week that government figures showed unemployment in Taiwan is at historic lows: “The local unemployment rate fell 0.02 percentage points from a month earlier to 3.30 percent in May, the lowest level for the month in 25 years.” Historical lows in joblessness occurred earlier this year as well. The context? Labor shortages. The National Development Council (NDC) expects that Taiwan will be short 400,000 workers by 2030, now just five years away. The depth of the labor crisis is masked by the hundreds of thousands of migrant workers which the economy absolutely depends on, and the

If you’ve lately been feeling that the “Jurassic Park” franchise has jumped an even more ancient creature — the shark — hold off any thoughts of extinction. Judging from the latest entry, there’s still life in this old dino series. Jurassic World Rebirth captures the awe and majesty of the overgrown lizards that’s been lacking for so many of the movies, which became just an endless cat-and-mouse in the dark between scared humans against T-Rexes or raptors. Jurassic World Rebirth lets in the daylight. Credit goes to screenwriter David Koepp, who penned the original Jurassic Park, and director Gareth Edwards, who knows