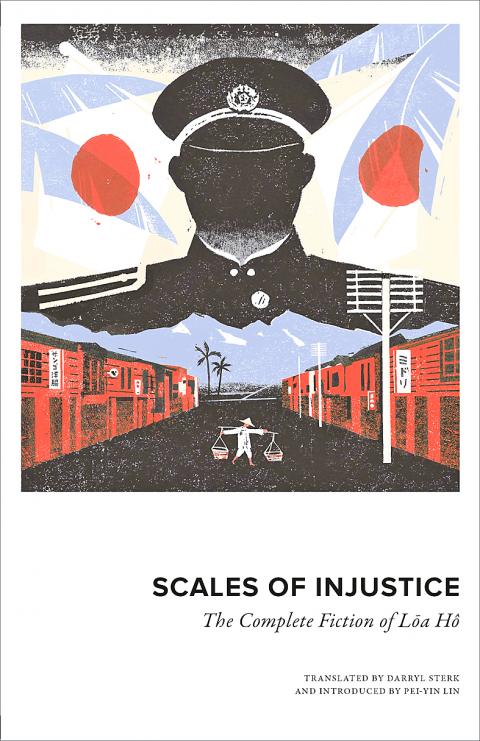

Honford Star is a new independent publisher, based in London and specializing in translations from East Asia. One of their first publications is a complete edition of the short stories of Loa Ho (賴河, 1894-1943), seen by many as the father of Taiwanese literature written in the vernacular.

Loa, also known as Lai He (賴和), wrote during the era of Japanese occupation. Born in Changhua County, he trained and practiced as a doctor, writing fiction only for a period of 12 years in the middle of his life. He was imprisoned twice, albeit for short periods, as a suspected opponent of the Japanese (the second time on the day of the attack on Pearl Harbor). He is consequently seen as both the father of Taiwanese writing in the vernacular and as a chronicler of Taiwan’s colonial era, with a special sympathy for the oppressed.

Darryl Sterk, the distinguished translator, explains in a note that he has felt free to expand the text where he felt a historical explanation was necessary, saying that the author appears to have often disguised his exact meaning in order to get his work past the censor.

Taiwanese Steinbeck

Loa may sound like a Taiwanese Chekhov, being both a doctor and a writer, but the tales themselves read more like Steinbeck. Here are stories of the plight of the ultra-poor, unable to buy presents for their children for the Lunar New Year because of fraudulent inspectors at the market where they work, and of growers of sugar cane defrauded by the company they work for, with its tampered-with scales and last-minute new regulations. In Steinbeck the response of the workers is usually political action, strikes and so forth. Here, the opposition to exploitation is confined to several stories put together in a special section, and is not especially effective.

The notes in this edition are hugely informative. Because, for instance, the subject-matter is so often people’s economic status, money looms large in these stories. So in a key note the translator explains how both the older Chinese terminology — k’uai (silver pieces) and kho (rounds) – and the newer Japanese terminology — yen — were used.

And in a story concerned with the trade in opium, By Chess and Go Boards, characters debate their attitudes to new licensing laws. After an initial attempt to stamp out opium use, we’re told, the Japanese adopted a system of licenses for both addicts and retailers. The term “roasting crows” was used to mean consuming the product because of a similarity of the characters in Chinese. The sale of opium wasn’t made illegal until the end of Japanese rule in 1945.

Some of these stories appear to have been written in response to changes in social conditions, so that a new law, for example, immediately becomes the topic of a Loa tale. Historians will thus value this collection as, in part, a running commentary on life in Taiwan in the 1920s and 1930s, the decades in which most of the stories were written.

Where an author is mentioned at all, Loa uses a pseudonym. Darryl Sterk renders these with some English equivalents — Lazy Cloud (the most common), Doc, Ash and so on. In addition, most of the stories have a date of publication appended, plus the name of the journal where the story first appeared, though for a significant number it’s stated that no date of composition is known.

Sterk says he found it impossible not to warm to Loa and his stories, and I have to agree. They also display a considerable range, moving from a conversation overheard in a train (Going to a Meeting), via a child taken into police custody on the Lunar New Year (A Disappointing New Year) and a cane sugar grower who refuses to complain when he’s denied a bonus (Bumper Crop), to a policemen — “patrolman” — killed by an exploited vegetable seller (A Lever Scale).

Hong Kong University’s Lin Pei-yin (林姵吟), author of Colonial Taiwan: Negotiating Identities and Modernity Through Literature (2017), supplies an informative introduction. In it she points to Loa’s criticisms of traditional Taiwanese attitudes, as well as providing useful insights into the politics of the Taiwan Cultural Association (it divided into left and right factions) during the Japanese era. She compares Loa to China’s Lu Xun (魯迅), though Loa was far less productive, and gives several reasons why he should be better known than he is.

Another topic of interest is Loa’s treatment of medical issues, seeing that he was himself a doctor. The Japanese apparently favored and promoted Western medicine, and considered Chinese herbal remedies ineffective, issues dealt with in Mr Snake and Hope for the Future. Traditional remedies don’t get much sympathy in either story.

Colloquial Style

Darryl Sterk’s style in these translations is pleasantly colloquial. Examples from just one item, The Story of a Class Action (published 1934), include “at the drop of a hat,” “up in arms,” “a class act,” an “opium fix” and “an afternoon snooze.” This story, incidentally, has an unusually optimistic ending and features an idealistic main character, a Mr Grove, though its relationship to Loa’s attitude is less significant than it might be by the story being set, untypically, before the arrival of the Japanese in Taiwan.

A Lever Scale (published 1926) is one of the best items. In it close attention is paid to the multiple ways the police could catch out the poor. “There were your travel regulations, traffic controls, rules of the road, rules concerning food and drink, and rules relating to weights and measures — lift a finger and you might be breaking some rule”. Loa adds a note to this story saying that he witnessed it himself but that it took him some years to dare to set it down. He was finally persuaded by the example of Anatole France.

Honford Star is to be congratulated on this publication. Let’s hope many comparable volumes will soon follow.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand