Dec. 4 to Dec. 10

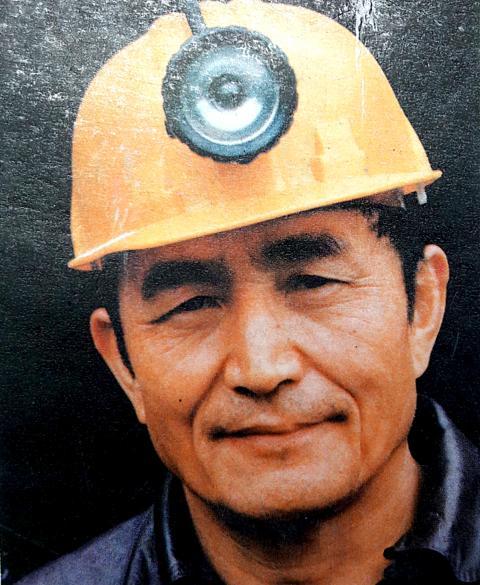

Chou Tsung-lu (周宗魯) prayed as usual before he headed into Haishan Tunnel No. 1 in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽) in the late morning of Dec. 5, 1984.

“I must pray every time because it’s quite dangerous down there,” he writes in his biography, Run from Death (突破死亡線), by Ho Hsiao-tung (何曉東). “If I don’t have the protection of Jesus, there’s a huge chance I’ll die.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Chou was about to start drilling when he was thrown to the ground by a violent burst of wind, knocking off his helmet. Smoldering coal dust scorched his face, and when it subsided he had to make sure he was still alive.

Screaming “Lord,” Chou ran as fast as he could out of the tunnel, past a charred body into a chamber where survivors were all frantically praying to different deities. He kept running upward and found an airpipe several levels above, which kept him alive as his 92 companions dropped one by one to carbon monoxide poisoning.

Surviving underground for 93 hours by drinking urine and eating human flesh, Chou was the sole survivor of the Haishan No. 1 Tunnel mining disaster, the final of three deadly incidents in 1984 that killed at least 270 miners and accelerated the demise of Taiwan’s coal industry.

Photo: Hsin Yue-hung, Taipei Times

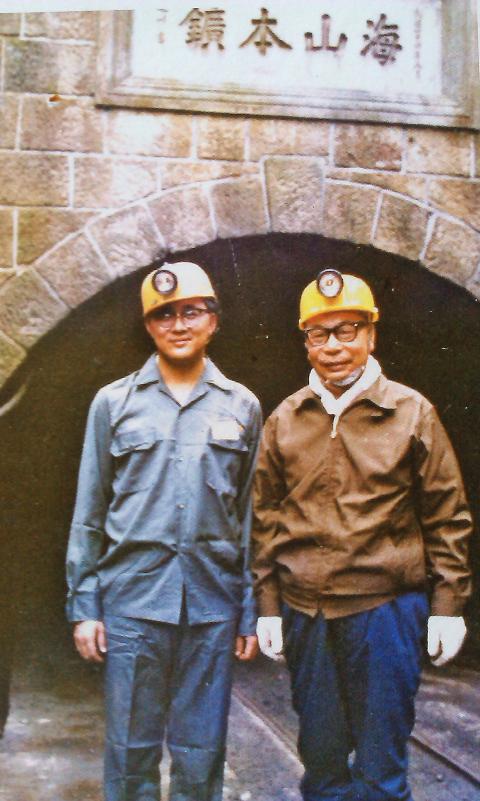

BOOMING INDUSTRY

The closing of Taiwan’s last operating coal mine in Sanxia in 2001 marked the end of 125 years of coal mining in the country, starting with the Badouzih mine (八斗子) in Keelung, which opened in 1856.

According to a document by the Chinese Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers, between 1945 and 1996, a total of 130 million tonnes of coal was procured from these underground passages, peaking between 1964 and 1969, when each year’s production exceeded 5 million tonnes. In 1967, an estimated 58,000 people toiled in 366 mines across the country.

Photo: Liu Yen-fu, Taipei Times

It was a dangerous operation, but with coal providing up to 60 percent of the nation’s energy in the 1960s, production was valued over safety and on average there were 83 accidents and 111 deaths per year between 1946 and 1969. The most common cause was falling rock, followed by gas and dust explosions.

The Bureau of Mines was established in 1970. It established safety laws and regulations in 1974 and 1976 and set up emergency response centers near mining districts. The death toll greatly decreased, with 22 in 1983. But things took a turn for the worse the following year.

On June 20, 1984, the first major disaster struck at the Haishan Mine (海山煤礦) in New Taipei City’s Tucheng District (土城). A rail car came loose and slid down a slope, hitting a high-voltage electric box and causing an explosion. Many survivors succumbed to carbon monoxide poisoning. The second incident on July 10 at Ruifang District’s Meishan Mine (煤山煤礦) was due to an electrical fire. The disaster Chou was involved in occurred due to an explosion of undetermined origin.

Photo courtesy of Huang Liang-yi

Taiwan’s coal industry was already struggling due to competition from imported coal and the advent of other types of energy such as petrol, and these deadly incidents only sped up the decline. By 2000, there were only four operating mines in Taiwan, all located in Sanxia.

The Haishan No. 1 Tunnel incident was not the first disaster Chou encountered. In 1979, he missed work for reasons he can no longer recall, narrowly avoiding several explosions in the Chungyi mine (忠義煤礦), also in Sanxia.

The Chungyi mine was one of the hottest and most dangerous mines — Chou says two miners could drink 5 liters of water in two hours. They also had fans blowing cold air from a block of ice, but Chou says they still tried to get in and out as quickly as possible.

Photo: Liu Yen-fu, Taipei Times

The conditions in Haishan Tunnel were much better, but Chou says he almost died there as well — once from accidentally inhaling poisonous gas from a wind pipe. The second time, he went into the tunnel unaware that there was an unexploded stick of dynamite hidden behind a rock. Luckily, his drill malfunctioned and only later did he find the dynamite right under where he was about to drill.

URINE AND HUMAN FLESH

After the mining disaster, Chou was afraid to leave his life-saving air pipe. Extremely thirsty, he urinated into his helmet and tried to drink it.

“No wonder people joked that it was ‘Shandong hot and sour soup,’” Chou writes. “I did not want to take another sip, but I didn’t want to dump it either. So I left it there, occasionally using the urine to wet my cracking lips.”

He dipped a cloth in urine and used it as a face mask to explore the area, finally finding half a sip of water left in a canteen. Later, he managed to find water dripping from a crevasse. It took two hours to fill up the canteen.

With his thirst quenched, Chou was now hungry. He had gone hungry before, going for several days without food while in the army and also took part in Christian fasts several times. There was absolutely nothing to eat in the tunnel, and Chou prayed: “Lord, I’m going to have to eat human meat.”

“God didn’t stop me, but who would find it an easy feat to eat human flesh — especially those of my compatriots?” he says. “Someone asked me later how human flesh tasted. I can’t really say — it was raw and I swallowed it with water without chewing.”

It took several attempts before Chou was able to swallow the piece of meat without vomiting it back out. This would impact his social reputation later on.

“After I was rescued, I heard someone say, ‘Chou Tsung-lu ate human meat, we can’t be friends with him anymore!’” Chou says.

A newspaper report came to his defense, announcing that it was not illegal to consume human flesh in dire situations, and also deemed the act acceptable from both Christian and Buddhist perspectives.

Chou now had enough energy to plan his escape — but the passageway was blocked. After frantically digging for a while, he retreated to his original location to wait for help. As he was about to give up on the fifth day, he returned to the blocked tunnel and found that there was now a small opening. He passed through and continued upward until he heard the voices of rescue personnel. He was saved.

In the aftermath, the Bureau of Mines conducted inspections of coal mines across the country, finding 70 of them not up to par. The Ministry of Economic Affairs also established stricter safety policies for coal mining the same year. There were still about 16,000 miners in Taiwan by 1984, but the government started phasing them out in 1985 by helping them find new professions and assisting the mines with severance pay.

By 1994, there were only about 1,000 miners left. When they retired, Taiwan’s coal industry was done for good.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand