Sept. 18 to Sept. 24

Kamimura Kazuhito was asked to resign after he attempted to lead his students at Tainan’s Presbyterian Middle School to pray at a Shinto shrine. In February of 1934, all Japanese teachers at the Christian school walked out in protest.

Ever since the colonial government made regular Shinto worship a requirement for private schools to be accredited, the issue had been a point of contention among school administrators. Without accreditation, students who wanted to attend university had no choice but to transfer to an accredited school.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Common

RETURN OF CHRISTIANITY

Missionaries were active in Taiwan during Dutch rule in the 1600s, but that ended when Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功, also known as Koxinga) conquered Tainan and kicked out the Europeans.

It would take about 200 years before the missionaries returned. Probably the most famous was the Canadian missionary George Leslie Mackay, who arrived in 1871 and built Taiwan’s first Western-style hospital, college and school for women in Tamsui.

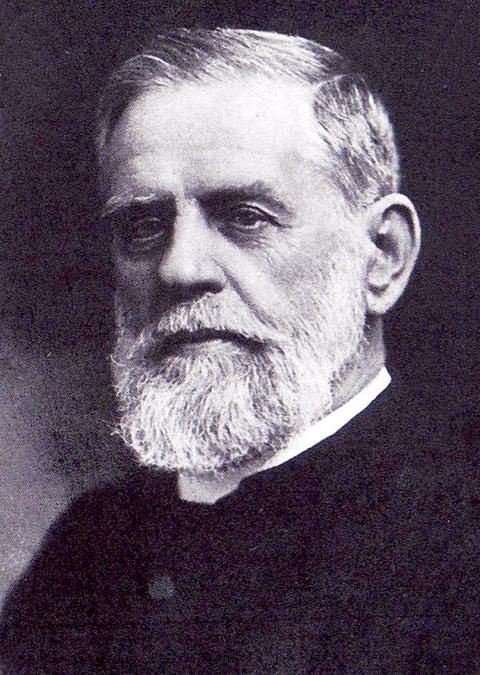

Photo courtesy of archive.org

Evangelists also flourished during this time in the south with the Presbyterian Church of England’s Tainan Mission Council. James Davidson writes in his 1903 book, The Island of Formosa, that there were 77 places of worship set up by the mission. The council also founded Taiwan’s first secondary school on either Sept. 21 or Sept. 24, 1885. Originally named Presbyterian Middle School, it continues to exist today as Chang Jung Senior High School (長榮高中).

The school’s founder and first principal was George Ede, an Englishman who arrived in Taiwan in 1883. Ede is mostly known for being the one who notified fellow missionary Thomas Barclay of the fleeing of Liu Yong-fu (劉永福), who was supposed to defend Tainan from the advancing Japanese occupation troops in 1895. Barclay led a delegation to the Japanese general’s headquarters, persuading them that the resistance had surrendered and inviting them to enter the city peacefully.

Ede left behind several books on theology, geography and Chinese literature in Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese) written in the Latin alphabet. But none of those can tell us about what life was like for the missionaries.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

For that, we turn to William Campbell, a Scotsman who arrived in Taiwan in 1871 and served a brief stint as interim principal for the Presbyterian Middle School. In 1915, he published a collection of essays, Sketches of Formosa, two years before he returned home.

BETTER THAN THE QING

Campbell appears hopeful during the onset of Japanese rule. Given “the determination of its rulers that Formosa, body, soul and spirit, must speedily be made an integral part of the Empire,” he predicts that the colonizers would bring better infrastructure, services and stability to Taiwan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“Of course, too, there will be things to vex the European merchant and the ardent Christian missionary, but patience must be exercised, and great things are still expected from such a people as the Japanese have proved themselves to be,” he writes.

In a later chapter titled “Europeans Get Fair Play Out Here,” Campbell argues that the missionaries were being treated much better by the people since the arrival of the Japanese.

“When I went to Formosa 25 years ago, a common taunt against the missionaries was that we were there to take over the island,” he writes.

“Now this has all been changed. The people have no loyalty to their present rulers … In contrast to the behavior of the Japanese, the people have come to appreciate the kind disposition of the missionaries. In many cases they are disposed to welcome rather than resist the entrance of Christianity into their villages.”

He follows by comparing missionary work under Qing and Japanese rule.

“The [Qing officials] were in no doubt required by law to tolerate Christianity, but they were ready to use underhand methods to hinder its successful propagation. The Japanese officials, on the other hand, know quite well that Christianity, as compared to Chinese heathenism, tends in the direction of civilization, good order and enlightenment, the very objects they are there to promote.”

According to Reflections on the Modernization of Christianity in Taiwan (反思百年基督教在台的現代化歷程), a study by Lee Chang-han (李長瀚), the Japanese indeed took a tolerant approach toward missionaries when it first took over in 1895, and Japanese missionaries even arrived to convert the Japanese residents of Taiwan.

IMPERIALISM TAKES OVER

The aforementioned Shinto policies were just the beginning of what would become a full-blown Japanization policy in the 1930s, where anything non-Japanese was banned. Campbell was probably fortunate to no longer be around to witness this.

Historian Lu Chi-ming (盧啟明) writes in a document for the National Taiwan Library that the Japanese started requiring all schools to teach solely in Japanese. The Presbyterian Middle School and its counterpart for girls were required to install Japanese principals and reorganize their board structures.

The schools managed to find two Japanese Christians to take the jobs, and after “extremely difficult negotiations” the schools were formally recognized in 1939 after changing their school names to what they are today.

Lu writes that the problem of Shinto worship remained a major issue, with the Japanese now threatening to close all schools that resisted. In addition, many Taiwanese Christians saw the schools as more than just religious institutions but also a public education service. Thus, they were more willing to make religious concessions to keep it open.

“The missionaries had no choice but to accept the Japanese explanation that praying at Shinto shrines is a patriotic behavior that supersedes religion,” Lu writes, noting that the Japanese Emperor Hirohito was worshipped as a divine being at the time.

The new principal of the middle school banned all Christian activities on school grounds, prompting missionaries to build a separate dormitory where worship carried on.

But with the increase in non-Christian students and limited space in the dormitories, these schools gradually lost their religious elements and became the secular institutions they remain today.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a