Brandishing their spears, swords and other weapons, the diminutive warriors glare at their rivals on the other side of the Siaoli River (霄裡溪).

Yelling battle cries, each side’s representative charges into the river on the back of a water buffalo. Actually, it’s more of a trot due to the buffalo’s slow pace, but the two sides eventually meet in the middle. Blows are exchanged, and Team Mimi’s fighter defeats her Team Lala rival by touching his body with her foam-tipped spear.

The children are in a frenzy, with some crying foul and others cheering loudly. They are all friends again when the battle ends, as they play on a self-made tire swing, swim in the river and enjoy being dragged around by the water buffalo on a wooden grass sled.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

It’s just another afternoon at the Water Buffalo School (水牛學校) in rural Hsinchu, a summer camp where children spend five days taking care of water buffalo, learning survival skills and exercising their creativity through different projects that vary week to week. The previous week focused on fine art, while the one before that saw children making floating devices.

After the fun, they head back to their “school building” to shower and enjoy some grass jelly before they start preparing firewood to make dinner. There are no shops in the vicinity, and the building is bare bones with no air conditioning and poor cell phone reception so the children — largely from urban areas — can experience a lifestyle from a simpler time.

A GREAT COMPANION

The camp is run by Peter Lee (李春信), an artist who began raising water buffalo about nine years ago. He became interested in eco-friendly farming methods after moving to rural Hsinchu.

“I wanted to learn how humans and water buffalo worked together before machines were invented,” he says. “I realized there’s much artistic value in water buffalo farming — the land is your canvas, and the human and the buffalo are your brush. So I started incorporating water buffalo culture into my art classes.”

Eventually, it evolved into summer and winter programs for children, while adults are welcome during farming season to help with the labor.

“The water buffalo is a great companion,” Lee says. “In the old days, children would interact with them and develop games involving the animals. I want them to spend time with the animals and even develop an emotional bond with them. Before they came, their understanding of bovines probably did not go beyond eating them for dinner.”

Lee also shows the children documentaries and discusses the aesthetic value of traditional farming culture developed over thousands of years. The water buffalo battle is a new element in the camp as Lee continues to devise ways for children to warm up to the buffalo quickly.

“At first they are nervous, but through the battle they will forget about their fears,” he says.

Lee adds that there needs to be constant adult supervision due to the sheer size of the animals, but the children will also train their reflexes and concentration by learning how to move around the buffalo, whether riding them or leading them to the pasture for grazing.

LEARNING TO BE GRATEFUL

Having grown up in a farming village, Lin Li-chi (林麗琪) says that she sent her two Taipei-raised children here to have a taste of her childhood.

“I want to let them know that life wasn’t easy when we were growing up,” she says. “At home, all they do is watch TV in an air conditioned room. There’s none of that here. Their father jokes that they’re here to learn how to be grateful.”

Liu Tzu-chien (劉子謙), who will be a sixth-grader next month, is from Hsinchu City had never played in a river until he arrived at the Water Buffalo School.

Liu says the main draw for him was riding the water buffalo, but he also came to enjoy activities such as making a fire and weaving rope from straw.

“It’s super fun to experience a traditional lifestyle,” he says. “[Lee] purposely chose a half-finished house so we can learn what it was like to live in the old days.”

The children have to clean the water buffalo dung everyday, which initially disgusted Liu. But soon, he learned about the many uses of buffalo feces, such as turning it into soap and using it as mosquito repellent.

“Once I learned that it has many functions, I didn’t find it gross anymore,” he says.

In late October of 1873 the government of Japan decided against sending a military expedition to Korea to force that nation to open trade relations. Across the government supporters of the expedition resigned immediately. The spectacle of revolt by disaffected samurai began to loom over Japanese politics. In January of 1874 disaffected samurai attacked a senior minister in Tokyo. A month later, a group of pro-Korea expedition and anti-foreign elements from Saga prefecture in Kyushu revolted, driven in part by high food prices stemming from poor harvests. Their leader, according to Edward Drea’s classic Japan’s Imperial Army, was a samurai

The following three paragraphs are just some of what the local Chinese-language press is reporting on breathlessly and following every twist and turn with the eagerness of a soap opera fan. For many English-language readers, it probably comes across as incomprehensibly opaque, so bear with me briefly dear reader: To the surprise of many, former pop singer and Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) ex-lawmaker Yu Tien (余天) of the Taiwan Normal Country Promotion Association (TNCPA) at the last minute dropped out of the running for committee chair of the DPP’s New Taipei City chapter, paving the way for DPP legislator Su

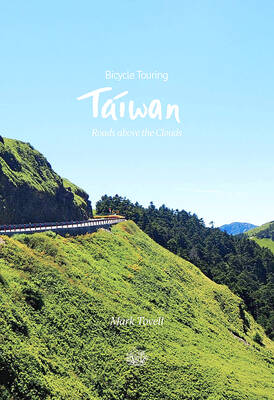

It’s hard to know where to begin with Mark Tovell’s Taiwan: Roads Above the Clouds. Having published a travelogue myself, as well as having contributed to several guidebooks, at first glance Tovell’s book appears to inhabit a middle ground — the kind of hard-to-sell nowheresville publishers detest. Leaf through the pages and you’ll find them suffuse with the purple prose best associated with travel literature: “When the sun is low on a warm, clear morning, and with the heat already rising, we stand at the riverside bike path leading south from Sanxia’s old cobble streets.” Hardly the stuff of your

Located down a sideroad in old Wanhua District (萬華區), Waley Art (水谷藝術) has an established reputation for curating some of the more provocative indie art exhibitions in Taipei. And this month is no exception. Beyond the innocuous facade of a shophouse, the full three stories of the gallery space (including the basement) have been taken over by photographs, installation videos and abstract images courtesy of two creatives who hail from the opposite ends of the earth, Taiwan’s Hsu Yi-ting (許懿婷) and Germany’s Benjamin Janzen. “In 2019, I had an art residency in Europe,” Hsu says. “I met Benjamin in the lobby