May 15 to May 21

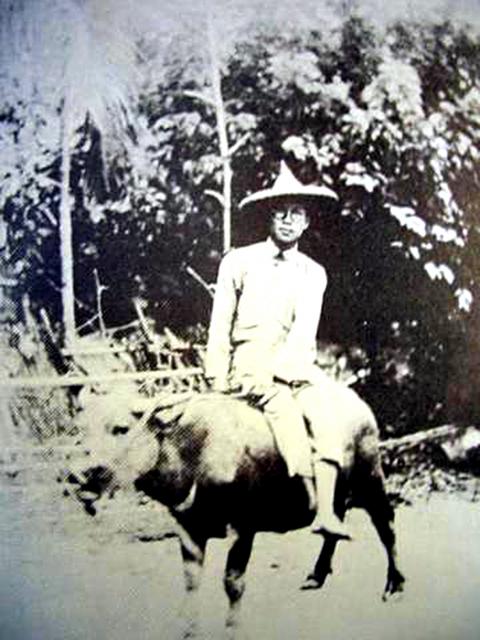

He was born exactly 85 years before farmers traveled to Taipei on May 20, 1988 to participate in what is considered Taiwan’s largest peasant movement since World War II. It’s probably a coincidence that they marched on his birthday, but Chien Chi (簡吉) was a notable peasants’ rights organizer during the Japanese colonial era, also leading a group of farmers to Taipei in 1926 to protest the government’s agricultural policy.

SEEDS OF DISCONTENT

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chien grew up in a farming family in what is today’s Fengshan District (鳳山) in Kaohsiung. He recalls that his parents had to “work like cows and horses,” and that his younger brother had to quit school to help in the fields. Chien was lucky enough to graduate from Tainan Normal School (台南師範學校) and became a local schoolteacher.

It was a respected position, but Chien’s discontent grew as he saw that many of his students suffered from lethargy after toiling in the fields after school, often missing class during the busy season.

“Although these children attend school, they are too exhausted for any education to be effective,” he told a judge while on trial years later for violating a publishing law. “I felt that I was a thief, earning a monthly salary for achieving nothing.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chien further detailed the hardships dealt to peasants in the Fengshan area by the Japanese government. Yang Du (楊渡) provides an overview of these injustices in his biography of Chien, The Man who Led Peasants (簡吉: 台灣農民運動史詩).

Starting around 1905, all arable land where the farmer could not prove ownership went to the state, causing them to lose their means of survival. Much of this land was later offered to retired Japanese officials to entice them to remain in Taiwan. The government also wanted to promote sugar production in Taiwan, intimidating peasants into selling the land at unreasonable prices to both Japanese and Taiwanese sugar manufacturers.

The government also seized land by dubious means. Chien mentions a case when the government forcefully purchased Fengshan farmland in 1906 to set up a “demonstration farm.” Yang Pi-chuan (楊碧川) writes in History of Taiwanese Resistance During Japanese Rule (日據時代台灣人反抗史) that by 1945, the colonial government had made public about 21 percent of Taiwan’s arable land.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The authorities encouraged farmers to grow sugarcane for the sugar factories, and they essentially became tenant farmers. As their only buyers, the factory owners exploited the farmers, who barely made enough to survive.

“I felt an infinite sadness watching this happen around me and decided to fight for their rights,” Chien concluded in his court statement.

TAKING UP THE FIGHT

Shortly after he left his teaching post, Chien became head of the Fengshan Peasants Union (鳳山農民組合). The first battle was against the local sugar factory, which had taken back land rented to tenant farmers to expand its facilities. With Chien leading the charge, the union convinced the factory to allow the peasants to farm for seven more years.

It was the first peasant victory in Taiwan, and Chien became a hero. He began touring the country’s farming villages, sharing his experiences and encouraging them to fight for their rights.

“He was the only ‘professional peasant revolutionary’ during Japanese rule, meaning that he had no other job,” Yang writes.

The government’s decision to offer land without clear ownership to retired officials in 1925 was the key event that would unite Taiwan’s farmers. Clashes between peasants and police broke out in several locations, and on June 28, 1926, five regional unions merged into the Taiwan Peasants Union with Chien in charge. A month later, Chien and fellow activist Chao Kang (趙港) led a group of farmers to Taipei to protest at the Governor-General’s office, but to no avail.

Activity intensified over the next few years, with more than 400 incidents between 1927 and 1928. Chien, a skilled orator, continued touring, sometimes attracting more than 1,000 people. By the end of 1928, the union boasted 27 branches.

Chang Hsien-tang (張獻堂) writes in The Study of Chien Chi and the Taiwan Peasant Movement (論簡吉與農民運動) that Chien’s rhetoric started to lean toward the left after he visited Japan in early 1927, when he won the support of Japanese socialist peasant revolutionaries.

For example, he wrote in a 1927 Taiwan Minpao (台灣民報) editorial, “We need to raise our class consciousness, unite and fight! Everyone should join the struggle for survival. Japanese capitalism is about to collapse, and so is global capitalism. We shall liberate everyone from oppression.”

Things started going downhill after 1928. The newly-formed Taiwan Communist Party (台灣共產黨) also had an interest in peasant rights, and the Japanese became wary of the collaboration between the two organizations. Chien earned his first jail sentence during a government crackdown on the union in 1929, but there was no evidence that he was a communist.

In 1931, the Japanese carried out another communist raid, and Chien received 10 years this time. Chien Chung-jen (簡炯仁) writes in an article for Taiwan Culture (台灣文化) magazine that in addition to the leaders being arrested, the peasant movement had stagnated since a large number of farmers had moved to cities after losing their land. Also, the government improved the tenant farming system, reducing the number of suffering farmers and their cause to rebel.

That was the same year Japan invaded Manchuria, and as its imperialism intensified, the government became less tolerant of unrest. The peasant movement fizzled out shortly after.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

Enter the Dragon 13 will bring Taiwan’s first taste of Dirty Boxing Sunday at Taipei Gymnasium, one highlight of a mixed-rules card blending new formats with traditional MMA. The undercard starts at 10:30am, with the main card beginning at 4pm. Tickets are NT$1,200. Dirty Boxing is a US-born ruleset popularized by fighters Mike Perry and Jon Jones as an alternative to boxing. The format has gained traction overseas, with its inaugural championship streamed free to millions on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Taiwan’s version allows punches and elbows with clinch striking, but bans kicks, knees and takedowns. The rules are stricter than the

“Far from being a rock or island … it turns out that the best metaphor to describe the human body is ‘sponge.’ We’re permeable,” write Rick Smith and Bruce Lourie in their book Slow Death By Rubber Duck: The Secret Danger of Everyday Things. While the permeability of our cells is key to being alive, it also means we absorb more potentially harmful substances than we realize. Studies have found a number of chemical residues in human breast milk, urine and water systems. Many of them are endocrine disruptors, which can interfere with the body’s natural hormones. “They can mimic, block

Nearly three decades of archaeological finds in Gaza were hurriedly evacuated Thursday from a Gaza City building threatened by an Israeli strike, said an official in charge of the antiquities. “This was a high-risk operation, carried out in an extremely dangerous context for everyone involved — a real last-minute rescue,” said Olivier Poquillon, director of the French Biblical and Archaeological School of Jerusalem (EBAF), whose storehouse housed the relics. On Wednesday morning, Israeli authorities ordered EBAF — one of the oldest academic institutions in the region — to evacuate its archaeological storehouse located on the ground floor of a residential tower in