Writer Lo Tao (羅濤) doesn’t see any reason not to set his stories in Taiwan and imbue them with Taiwanese elements — even if the product is a video game featuring a gay character who romances anthropomorphic animals.

Lo is the primary writer for Nekojishi (家有大貓), which features characters inspired by Taiwanese folklore. He is among a growing number of comic artists, game producers and other creative types looking to local history and culture for inspiration. They don’t feel that the relative obscurity of Taiwanese culture is a barrier to marketing. Indeed, they are convinced it will appeal to local consumers as something familiar and also pique the curiosity of foreigners.

“My story happens in Taiwan, so it’s a given that it’s going to have Taiwanese elements. But making the game fun and telling a good story are more important,” he says. “And if people learn more about Taiwanese culture after playing it and want to delve deeper, well, that’s great.”

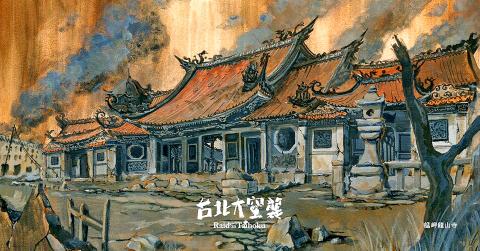

Photo courtesy of Teenage Riot Studio

CHANGING TAIWANESE-NESS

This type of thinking was not always the case, and most Taiwanese grew up with Japanese or American comics, cartoons and games. Even if there were products by Taiwanese creators, they mostly followed a foreign style.

In fact, people once pooh-poohed “Taiwanese-ness.” KJ Chang (張少濂), who is part of a team developing a board game based on the 1945 Taipei Air Raid, says that referring to someone as hentai (很台, “very Taiwanese”), it implies an unrefined person with poor taste in dress and manner.

Photo courtesy of Nekojishi

“It’s ridiculous to use one’s own birthplace to describe something like that,” he says. “And when designers make something refined, people will say, ‘Oh, that’s very Japanese.’ They don’t realize that Taiwanese style is simply moving in a more positive direction.”

Chang says that the shift is due to the increased civic awareness of recent years.

“Young people are starting to search for their roots,” he says.

Photo courtesy of Zuo Hsuan

Zuo Hsuan (左萱) is the author of The Summer Temple Fair (神之鄉), a comic book revolving around the santaizi (三太子) religious procession in her hometown of Dasi (大溪) in Taoyuan. She says Taiwanese-ness can go beyond the religious and folk elements, as even something as mundane as buying noodles can be uniquely Taiwanese.

“A Taiwanese doing or reacting to something will certainly be different from an American or Japanese doing the same thing,” she says. “Also, I think my dialogue is very Taiwanese too.”

Zuo says that she grew up reading Japanese comics, but recalls that when she and her friends would draw comics at school, it would always be about their daily lives.

“You can find much inspiration in your surroundings,” she says. “I think more Taiwanese are starting to discover that there are many topics around them that they can expand upon.”

Despite Nekojishi’s themes of homosexuality and furry subculture, this “every day life” notion is also what Lo strives for. He says that he has given all the characters realistic names, such as an anthropomorphic leopard cat named Yen Shu-chi (嚴書齊).

“This is a story that happens in modern day Taipei, and I wanted to portray it as realistically as possible,” he says. “That goes for my characters too. I’ll give them conventional names.”

“The main character is a pretty regular person, just like most of our audience,” Lo’s teammate Sheng Hang (聖航) adds. “It’s his experiences that are unusual.”

EXTENSIVE RESEARCH

Chang says when he surveyed 40 young people in Ximending, only two knew about the Taipei Air Raid, which heavily damaged Taipei and killed many people. Even Chang only heard his father talk about it a few times.

“There are many gaps in our historical memory,” he says. “Taiwan has been ruled by too many different people with different educational agendas.”

But it’s exactly this general unfamiliarity with Taiwanese history and culture that makes the subject a treasure trove for creative inspiration, Chang adds.

“We’re not like Americans or Europeans who seem very familiar with their history,” he says. “There are still many local stories waiting to be found, and as Taiwanese we are the best candidates to interpret them because they belong to us.”

Chang’s team has gone to great lengths to keep their game historically accurate, consulting experts on topics ranging from the damage to the buildings to the characters’ interests to what people would name their cats and dogs in that era.

“Since this topic is uniquely ours, it’s up to us to make it as detailed as possible,” designer Boyea Lai (賴柏燁) says.

Most of Lo’s team also had no idea about the Tiger Lord (虎爺) mythology featured in the game, and he also consulted with Aboriginals for a snow leopard character from the Rukai tribe. And even Zuo, who grew up watching the Santaizi procession, spent about two years researching and experiencing the ceremony to present an authentic picture.

NO PREACHING

Although Taiwanese elements are prevalent in all three productions, Zuo, Chang and Lo all say that it should not be treated as a gimmick to attract attention, nor should the product be overly preachy about Taiwanese culture.

Lo says if people want to learn more about the cultural terms brought up in Nekojishi, they can visit a separate information section. And the producers give people a special gift as incentive to visit and pray at a Tiger Lord temple after they play the game.

“If you overly emphasize Taiwanese culture, it will destroy the flow of the game,” he says. “People just want to relax and play, and you’ll ruin that by dumping a bunch of knowledge on them. We want them to like the game first, not tell them what they should learn.”

Chang takes a similar approach. The team has detailed all the American airstrikes in Taiwan during World War II in two books that can be ordered separately.

Zuo says that even though her comic revolves around religious practices, the story of friendship, family and homecoming is what will attract people.

“It won’t feel like a class if you’re learning through a comic,” she says. “You’ll absorb the material naturally.”

Chang adds that people should not overly rely on the attention created by making something Taiwanese, as Taiwanese-ness alone will not be enough.

“[Author] Giddens Ko (柯景騰) once said, ‘I don’t support Taiwanese movies. I only support good movies,’” he says. “Many foreigners have taken an interest in our game because they love the artwork. We have to make something that is competitive internationally regardless of how Taiwanese it is. That’s the direction we are moving towards.”

Last week the story of the giant illegal crater dug in Kaohsiung’s Meinong District (美濃) emerged into the public consciousness. The site was used for sand and gravel extraction, and then filled with construction waste. Locals referred to it sardonically as the “Meinong Grand Canyon,” according to media reports, because it was 2 hectares in length and 10 meters deep. The land involved included both state-owned and local farm land. Local media said that the site had generated NT$300 million in profits, against fines of a few million and the loss of some excavators. OFFICIAL CORRUPTION? The site had been seized

Next week, candidates will officially register to run for chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). By the end of Friday, we will know who has registered for the Oct. 18 election. The number of declared candidates has been fluctuating daily. Some candidates registering may be disqualified, so the final list may be in flux for weeks. The list of likely candidates ranges from deep blue to deeper blue to deepest blue, bordering on red (pro-Chinese Communist Party, CCP). Unless current Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) can be convinced to run for re-election, the party looks likely to shift towards more hardline

The depressing numbers continue to pile up, like casualty lists after a lost battle. This week, after the government announced the 19th straight month of population decline, the Ministry of the Interior said that Taiwan is expected to lose 6.67 million workers in two waves of retirement over the next 15 years. According to the Ministry of Labor (MOL), Taiwan has a workforce of 11.6 million (as of July). The over-15 population was 20.244 million last year. EARLY RETIREMENT Early retirement is going to make these waves a tsunami. According to the Directorate General of Budget Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS), the

Sept. 15 to Sept. 21 A Bhutanese princess caught at Taoyuan Airport with 22 rhino horns — worth about NT$31 million today — might have been just another curious front-page story. But the Sept. 17, 1993 incident came at a sensitive moment. Taiwan, dubbed “Die-wan” by the British conservationist group Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), was under international fire for being a major hub for rhino horn. Just 10 days earlier, US secretary of the interior Bruce Babbitt had recommended sanctions against Taiwan for its “failure to end its participation in rhinoceros horn trade.” Even though Taiwan had restricted imports since 1985 and enacted