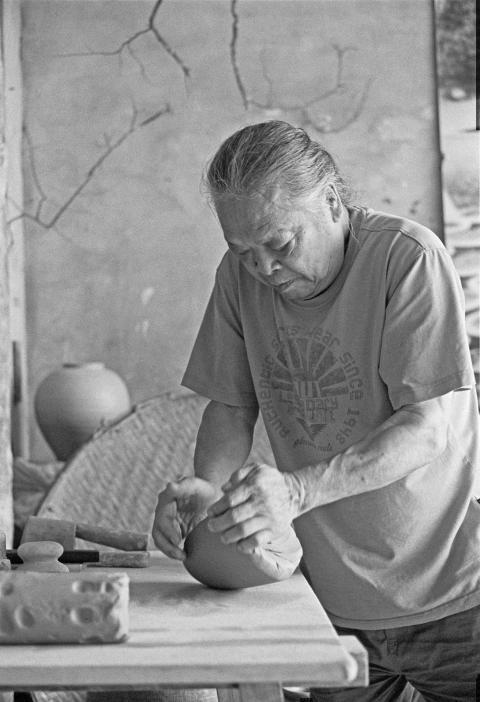

Wu Cheng-hung (吳正宏), 77, is the 23rd generation of a line of potters that started in Cizao Township (磁灶鎮) in 5th century China. His grandfather, Wu Ji (吳及, 1878 to 1949), left Cizao at the end of the Qing dynasty to make a living in Taiwan, bringing the coiling technique and kick wheel technology practiced in Cizao with him. When Wu visited his ancestral town in 1999, he discovered that the traditional pottery industry there had all but disappeared.

Wu’s daughter-in-law Lai Hsiu-tao (賴秀桃) — a potter in her own right — says that in the past, almost every household in Cizao was involved in producing pottery.

“When [Wu] returned, nobody was making pottery” Lai says. “Times change,” she adds.

Photo: Paul Cooper, Taipei Times

Wu has lived in Yingge (鶯歌), a pottery producing area in New Taipei City, since he was three. He continues to use the Cizao practices. Even after the invention of the electric potter’s wheel made the kick wheel obsolete, Wu still finds value in passing on the method to future generations.

Lai says that Wu is unique in that he is skilled in both coiling and the kick wheel.

“Factories have simplified the process. He hasn’t, and that is very rare,” she says.

Photo: Paul Cooper, Taipei Times

WHERE IT ALL STARTED

Wu’s ancestors started making pottery in the late Song Dynasty in Cizao, a town once full of small family-owned kilns making functional wares. It is located at what was once the southern end of the maritime silk road, and wares from there were exported via the port of nearby Quanzhou (泉州) to Japan, Korea, Penghu, the Philippines, Burma, Thailand, India and Indonesia.

When Wu’s grandfather emigrated to Taiwan, he introduced the kick wheel to Shalu District (沙鹿) in Taichung County, and soon it was adopted throughout the nation. He was originally reluctant to teach the technique to his son, Wu Wen-sheng (吳文生), but he eventually conceded, and Wen-sheng later passed them on to Wu Cheng-hung who, in turn, has passed them on to his own son, Wu Ming-yi (吳明儀).

Photo: Paul Cooper, Taipei Times

Before the invention of the electric potter’s wheel, potters employed other ways to keep the wheel spinning fast enough, consistently and for long enough, to throw pots. This was done either by “kicking” it or operating a lever.

In Korea, where they made large urns, they would dig a hole and set a wheel into the ground. The Japanese, who made small tea bowls, elevated the wheel to the height of the seated potter.

The kick-wheel method used in southern China employed a heavy wheel, roughly a meter in diameter, formed of fired clay held together with matted plant material and set on an axis on the floor.

Wu places the clay in the center of the wheel. Then, supported on one leg, he sets his free foot on the outer rim and starts to turn the wheel, building a momentum that is maintained by the wheel’s sheer weight. He then sits down and starts throwing the pot. When the momentum fades and the wheel slows down, he stands again and repeats the kicking process.

He completes a medium-sized pot in two minutes. He hasn’t broken a sweat.

That’s not to say the technique isn’t hard work.

“In the past, potters would be using the kick wheel like that, all day, every day. It was very laborious, exhausting work,” Lai says.

Technological advances drive progress. All innovations are eventually superseded. The energy-intensive nature of the work aside, there are many other reasons to doubt the need to pass on these old methods.

OBSOLETE TECHNOLOGY

Wu himself admits the technology is obsolete.

“It’s not like everything I make is thrown on the kick wheel. It’s too tiring. Times have changed. We have electric wheels now,” he says.

Wu answers in the negative when I ask if using the kick wheel method gives a potter a competitive edge.

“Business people aren’t interested in whether an object is beautiful. You only make money from pots if you can make them in bulk,” he says.

Wu thinks that it is about more than commercial viability, however.

“The old ways do have an artistry about them,” he says, and, while nowadays many wares are made using prepared molds, “they just don’t have the same kind of feeling.”

Wu is well aware of how Yingge itself has changed — he saw his own father’s work evolve, and now sees his son making art, not functional wares. He has seen how commercial realities have transformed the industry of his own ancestral town. As a businessman himself, he knows full well the importance of keeping production costs down and output up.

So why keep it alive? And why pass it on to his son?

“It’s the culture of the past,” he says. “You cannot throw that away.”

Yingge Town Artisan is a monthly photographic and historical exploration of the artists and potters linked to New Taipei City’s Yingge Town.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

Desperate dads meet in car parks to exchange packets; exhausted parents slip it into their kids’ drinks; families wait months for prescriptions buy it “off label.” But is it worth the risk? “The first time I gave him a gummy, I thought, ‘Oh my God, have I killed him?’ He just passed out in front of the TV. That never happens.” Jen remembers giving her son, David, six, melatonin to help him sleep. She got them from a friend, a pediatrician who gave them to her own child. “It was sort of hilarious. She had half a tub of gummies,