Sept. 12 to Sept. 18

Before Independence Evening Post (自立晚報) reporters Lee Yung-teh (李永得) and Hsu Lu (徐璐) set out on their historic journey as the first Taiwanese reporters to visit China on Sept. 14, 1987, they reportedly requested that they not be hosted by government officials, they would pay their own way and they would be able to report freely.

However, during the press conference upon arrival at Beijing’s airport, a Reuters reporter asked them, “Do you really believe that you will be able to report freely in China?” Lee and Hsu then asked for his opinion. “I cannot tell you,” he replied, and the crowd of foreign reporters erupted in laughter.

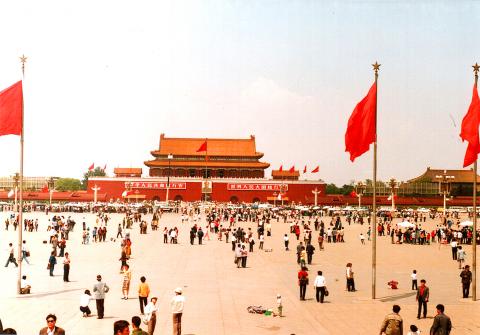

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Lee and Hsu write in their book, Historic Journey to the Mainland (歷史性 大陸行) that they had already noticed that they were being followed on their first day in Beijing. When the duo questioned their hosts, China News Service, about the situation, they were told that it was for their safety, as there were “some people who did not approve of their visit.”

Even when Lee and Hsu were able to score an interview on their own, the source insisted that they bring their hosts along. In other situations, the hosts would also insist on arranging all the transportation and accompany them for “safety” issues. A foreign reporter told them that sometimes he would have to run as fast as he could to buy a few precious minutes to speak to passersby without supervision.

Phone calls to their hotel were also “filtered” by the operator, who turned away people who wanted to privately contact them without official notice. Those who finally got through told them about all the political hurdles they had to pass to get in touch with them.

Photo: Wang Min-wei, Taipei Times

“To be frank, all our requests while we were in China were respected on the surface … but we were surrounded by an invisible net and only felt increasing pressure,” Lee and Hsu write. They cite a Taiwanese who once said that upon finally achieving his dream of visiting the “motherland,” he only felt unfamiliarity and fear.

“In those 13 days we reported in China, in the bottom of our hearts were exactly this indescribable ‘unfamiliarity and fear,’” they write.

A DARING PLAN

Photo: Liu Hsin-teh, Taipei Times

Frank Wu (吳豐山), then-president of the paper, details his decision to send reporters to China in the introduction of Lee and Hsu’s book.

“On this planet, Taiwan and China are the closest to each other, but also the furthest because of political issues,” he writes. “This is not beneficial to Taiwan’s long-term future. Reporters from other countries have visited China — but the viewpoint of a foreigner or even a Chinese living overseas would be totally different from ours, and would not serve as a useful reference.”

There had been talks of allowing Taiwanese to visit their relatives in China since March 1987, and by September the general guidelines were set, prompting Wu to set his plan into motion.

Wu informed editor-in-chief Chen Kuo-hsiang (陳國祥), and they decided to send Lee and Hsu. Wu also decided not to inform the publisher or chairman until the two left the country. Lee and Hsu flew to Japan first on Sept. 11, upon which Wu made a public announcement.

“While waiting for their flight, the three of us had lunch at the airport,” Wu writes. “The two were calm and collected, with frequent mentions of ‘we are writing history.’”

The government ordered the newspaper to recall the reporters, but Chen refused, stating that it would not only look bad for the newspaper, but also make the government look bad in trying to suppress freedom of the press. By this time, martial law had been lifted for four months.

On Sept. 14, Wu met with then-head of the Government Information Office Shao Yu-ming (邵玉銘), telling him, “Since the government has allowed visitation of relatives in China, as the press, it is our duty to serve as a vanguard for our readers,” and reiterated that he would not recall the reporters.

That same day, Lee and Hsu received their Chinese visas and boarded a flight from Tokyo to Beijing. Wu recalls receiving as much supportive letters as ones denouncing the paper.

A CURSORY LOOK

Lee and Hsu write that one main takeaway from the trip was how “fossilized” the government anti-Communist propaganda in Taiwan was.

“Regarding the general standard of living, China is indeed behind us, but we cannot ignore their attempts to reform. The Chinese Communist Party may have terrorized its population with the Gang of Four incident and the Cultural Revolution, but it has regained their trust through economic reforms,” they write.

They spent time in Beijing, visited West Lake in Hangzhou and also stopped by Guangzhou and Xiamen, detailing their observations. They were able to interview Fang Lizhi (方勵之), a political dissident whose ideas inspired the 1987 pro-democracy student movement.

Lee and Hsu write in the book’s introduction that from a journalistic standpoint, they were not happy about the trip as they were only offered a cursory look of a land that had been closed off to them for so long.

“But it is a real documentation completely through the eyes of Taiwanese reporters and not filtered through the perspective of a foreigner,” they add. They conclude by stating that they hope for more mutual understanding and that both sides stop using political propaganda to defame and uglify each other.

Upon Lee and Hsu’s return on Sept. 27, the government banned the Independence Evening News from sending any reporters overseas for two years and also arrested Wu, Lee and Hsu for forgery of public documents, claiming that they had applied to visit Japan but went on to China.

After a lengthy court case, the defendants were acquitted — perhaps an indication that times were changing.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

The primaries for this year’s nine-in-one local elections in November began early in this election cycle, starting last autumn. The local press has been full of tales of intrigue, betrayal, infighting and drama going back to the summer of 2024. This is not widely covered in the English-language press, and the nine-in-one elections are not well understood. The nine-in-one elections refer to the nine levels of local governments that go to the ballot, from the neighborhood and village borough chief level on up to the city mayor and county commissioner level. The main focus is on the 22 special municipality

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Hsu Pu-liao (許不了) never lived to see the premiere of his most successful film, The Clown and the Swan (小丑與天鵝, 1985). The movie, which starred Hsu, the “Taiwanese Charlie Chaplin,” outgrossed Jackie Chan’s Heart of Dragon (龍的心), earning NT$9.2 million at the local box office. Forty years after its premiere, the film has become the Taiwan Film and Audiovisual Institute’s (TFAI) 100th restoration. “It is the only one of Hsu’s films whose original negative survived,” says director Kevin Chu (朱延平), one of Taiwan’s most commercially successful

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the