Bruce Lee (李小龍) was 14 years old, and on the losing end of several street fights with local gang members, when he took up kung fu.

It was 1955, and Hong Kong was bustling with schools teaching a range of kung fu styles, including close-combat techniques and a method using a daunting weapon known as the nine-dragon trident.

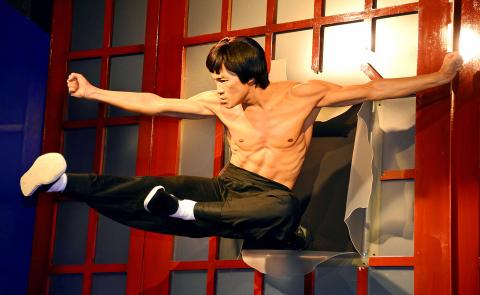

Lee’s decision paid off. After perfecting moves like his 1-inch punch and leaping kick under the tutelage of a grand master, he became an international star, introducing kung fu to the world in films like Enter the Dragon in 1973.

Photo: EPA

Decades later, cue the dragon’s exit.

DECLINE OF AN ART

The kung fu culture that Lee helped popularize — and that gave the city a gritty, exotic image in the eyes of foreigners — is in decline. Hong Kong’s streets are safer, with fewer murders by the fierce crime organizations known as triads that figured in so many kung fu films. And its real estate is among the world’s most expensive, making it difficult for training studios to afford soaring rents.

Photo: Reuters

Gone are the days when “kung fu was a big part of people’s cultural and leisure life,” said Mak King Sang Ricardo, the author of a history of martial arts in Hong Kong. “After work, people would go to martial arts schools, where they’d cook dinner together and practice kung fu until 11 at night.”

With a shift in martial arts preferences, the rise of video games — more teenagers play Pokemon Go in parks here than practice a roundhouse kick — and a perception among young people that kung fu just isn’t cool, longtime martial artists worry that kung fu’s future is bleak.

“When I was growing up so many people learned kung fu, but that’s no longer the case,” said Leung Ting, 69, who has been teaching wing chun (詠春), a close-combat technique, for 50 years. “Sadly, I think Chinese martial arts are more popular overseas than in their home now.”

According to Leung’s organization, the International WingTsun Association, former apprentices have opened 4,000 branches in more than 65 countries, but only five in Hong Kong.

Few kung fu schools remain in Yau Ma Tei, a district of Kowloon that was once the center for martial arts. Nathan Road — where the young Bruce Lee learned his craft from Ip Man (葉問, often spelled Yip Man), the legendary teacher who was the subject of Wong Kar-wai’s (王家衛) 2013 film The Grandmaster (一代宗師) — is now lined with cosmetic shops and pharmacies that cater to tourists from the mainland.

Though he lives in Yau Ma Tei, Tony Choi, a recent college graduate, has never been tempted to check out the remaining schools. Choi, 22, said that “kung fu just never came to mind.”

He added, “Kung fu is more for retired uncles and grandpas.”

When they do train in martial arts, younger people here tend to pick Thai boxing and judo.

DISCIPLINE THROUGH HARD WORK

In English, kung fu is often used as an umbrella term for all Chinese martial arts. But in Chinese, it refers to any discipline or skill that is achieved through hard work.

Kung fu traces its history to ancient China, with hundreds of fighting styles developing over the centuries. But it soared in popularity at the beginning of the 20th century, as revolution swept the nation.

After the fall of the Qing dynasty a century ago, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) used martial arts to promote national pride, setting up competitions and sending an exhibition team to the Olympics. But the government also tried to suppress wuxia (武俠), a martial arts genre of literature and film, as superstitious and potentially subversive.

When the Nationalists fell in 1949, the new Communist government in Beijing sought to control martial arts. The Shaolin Temple, said to be the home of Asian martial arts in central China, was ransacked during the Cultural Revolution of 1966-76 and its Buddhist monks jailed.

Throughout those decades, martial artists from China sought refuge in what was then the British colony of Hong Kong.

By the 1970s, kung fu fever had spread around the world. In addition to Bruce Lee’s films, the television series Kung Fu, starring David Carradine, became one of the most popular programs in the US.

Though Hong Kong’s kung fu films do not draw the attention they once did, the genre has influenced a generation of directors, including Quentin Tarantino and Ang Lee, and the actor Jackie Chan and others have kept it alive as comedy.

In a twist, kung fu has enjoyed a renaissance in China, where the government has standardized it and promoted it in secondary schools as a sport known as wushu to foster national pride.

As the martial arts center of gravity shifts to the mainland, some in Hong Kong have expressed hope that the government might support a revival here, too. Others are trying to carry on the tradition themselves.

Li Zhuangxin, a trim 17-year-old, has been studying the wing chun technique for more than four years. He was inspired by his grandfather, a devotee of the fighting style hung ga who gave Li his first kung fu lesson at age 8.

He hopes to open his own kung fu school one day — maybe on the mainland, where interest is higher and rents are cheaper — and has already set up a small wing chun club, with eight members, at his high school.

Few of his classmates had ever heard of wing chun before. Li, undaunted, says he wants to impart “the concentration and determination of kung fu” to his friends, who he laments are “only interested in playing with their cellphones.”

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.