One year ago, my idea of good alcohol was Taiwan Beer, or a Singapore Sling, if I wanted to be classy. A craft beer-loving friend from Michigan visited and I wracked my brain trying to figure out where in Taipei to bring him. I inadvertently stumbled into a growing craft beer scene when I discovered 55th Street. I’ve been drinking my way through northern Taiwan since — ales, stouts, porters — anything that wasn’t Taiwan Beer.

This is my last story in the “Drinking Taipei” series. Ironically, I decided to head down to Pingtung County (屏東) earlier this week to find out how southerners drink their beer.

Chung Wen-ching (鍾文清), the founder of Hengchun 3000 Brewseum (恆春3000啤酒博物館), laughs at me.

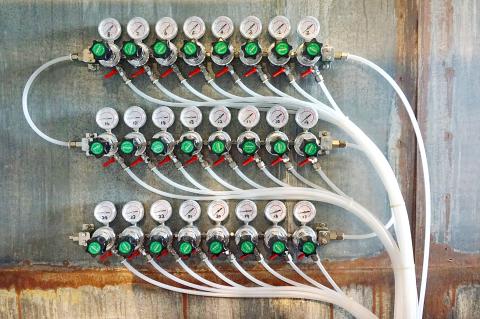

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

“There is no craft beer culture in the south,” he says.

He’s bewildered as to why I would make the four-hour trek down here. Though it’s located in an industrial district — laws confine breweries to industrial districts — the brewery/museum is shrouded in palm trees and banana trees. The Pacific coastline near the southernmost tip of Taiwan is a 20-minute drive away, but I can almost smell the saltwater.

It’s a weekday afternoon. Me, two little girls, a couple and a grandma are in the ground floor tasting hall which is a long and narrow space with wooden chairs and tables. They are taking selfies and sipping water. I down my pint of IPA.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

3000 beer mugs and glasses line the two-story high steel wall of the tasting hall. They were all purchased on e-Bay, Chung tells me.

From 1946, during the Chinese Civil War, to 2002, when Taiwan joined the WTO, Taiwan Beer held a monopoly.

“Beer to Taiwanese meant Taiwan Beer,” says the bespectacled, smiling Chung.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

“It meant sitting around a rechao (熱炒), talking really loudly with friends and clinking glasses and saying ‘bottoms up!’” he adds, referring to the roadside restaurants which serve copious amounts of fried meat and veggies.

Chung was part of the first wave of Taiwanese brewers to open craft breweries after 2002. These breweries were mostly unsuccessful because local palates weren’t quite ready for the bitter brews. It wasn’t until the second wave, post-2012, when younger brewers, including Taiwanese who had lived overseas and expats, that craft beer started to become popular.

“I’m just a bit older than the young brewers up north,” Chung chuckles.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

Chung first learned about craft beer in 1996, when he read about microbreweries in the US. In 2003, he completed a six-month apprenticeship with the American Brewers Guild in California and worked in a couple of brewpubs before returning to Taiwan to open his own brewery in Kaohsiung in 2005.

During his time in the US, Chung drank mostly lagers. It wasn’t until a few months into working at a San Francisco brewpub that he started to enjoy pale ales.

“It’s really an acquired taste,” he says.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

The Kaohsiung brewery ran for four years. After it closed down, Chung never stopped collecting beer-related trinkets and antiques from e-Bay. His collection includes replicas of beer recipes from Mesopotamia chiseled on stone and translated hieroglyphics from ancient Egypt, which describe the joys of intoxication.

The idea to open a brewery/museum — a “brewseum” as he calls it — came to him quite suddenly. He packed up his memorabilia and relocated from Kaohsiung to Hengchun where skies are clearer and the surf beckons.

Chung says that the new location is more ideal because travelers will stop by on the way to Kenting, and even if they didn’t want to drink beer, they will sit for a meal or browse the museum. Never mind the fact that they have eight different types of brews from the Manjhou Cream Ale (滿州) to Longpan Brown Porter (龍磐) — all named after places in Pingtung.

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

Be sure to ask Chung to give you a tour of the exhibition area which is on the upper level. He’ll tell you facts such as how in ancient Egypt, it was the women who brewed beer and the men who made wine, and that in late 18th to early 19th century England, families would brew beer when their child was born and store it for 21 years before giving it to them to drink.

“People were a lot more patient back then,” Chung says. “It’s not like today, where we’re creating a new brew every few weeks.”

Apparently, beer was consumed on nearly every corner of the earth at one point or another, and Chung has replicas of Mesopotamian beer gourds and actual ancient Chinese scrolls dating back to before the Han dynasty to prove it (yellow wine and rice wine, it turns out, became the choice of beverage after the Han dynasty).

Photo: Dana Ter, Taipei Times

Most bizarre is Chung’s collection of ales from the UK’s Bass Brewery dating back from 1869 to the 1970s. I ask him if there’s beer inside.

“Of course,” he says. “But you might not want to drink it.”

I ask Chung if he thinks the craft beer scene in the south will gradually expand. He’s firm in his reply: no. But he doesn’t mind. Teaching visitors to his brewseum about how Abbeys in 19th-century Europe brewed beer is his passion.

He thinks that in the south, the culture of gathering together a group of friends, sitting around a table at a rechao joint or in someone’s home and downing Taiwan Beer, is too embedded.

“But it’s also what makes the drinking culture in Taiwan special,” he says.

It’s been a tasty ride. I would like to thank all the bars and breweries for the beer. My refrigerator is stocked.

Getting there

Take the high speed rail from Taipei Main Station to Zuoying (左營). Get on the Kenting express (bus no. 9189) from Zuoying to Hengchun (恆春) station. Hengchun 3000 is a five-minute walk. Total commute is over 4 hours.

Drink Taipei:Taipei is a city that has positioned itself as being cheap and fast, but the revolution for craft drinks is taking wind and alcohol aficionados are thirsty for more. Drinking Taipei is a monthly column devoted to spotlighting chic, conceptual bars that aren’t your typical watering hole.

Warning: Excessive consumption of alcohol can damage your health.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is