Will, Julianna Barwick, Dead Oceans

Opposite tendencies can develop in culture at the same time. Look in one direction, and you see complex thought compressed into 140 characters, high-resolution video and audio, the sharpening of the pop-song hook: a process of individuation, definition, concision. Look in another direction, and the waters are rising. A song is a mixtape is an album is a video is a Soundcloud or a YouTube stream; no format seems to have primacy. Length and repetition aren’t a problem. Blurriness, in sound and meaning, may be a plus.

Julianna Barwick’s music belongs to the oceanic category. Her songs are built of short-cycle vocal lines, singing for the feeling, singing for the sound. They’re echoed and stacked, with indistinct words, and the instrumental aspects of the music sound like voices, too: continuous tones in repeating patterns. The effect is churchly and vaguely Renaissance, but also very now.

On Will, her third full-length solo studio album, Barwick is working with only a few others: singer Thomas Arsenault, who performs as Mas Ysa; cellist Maarten Vos; and percussionist Jamie Ingalls, from Chairlift, among other bands.

Being part of a larger tendency — which could be called ambient music but is really the echoed-and-repeated-vocal subcategory thereof — Barwick has been cheerful in interviews about the artists she’s compared to. Sometimes it’s Brian Eno. (On this record, Big Hollow, with its single-note piano line, recalls his early ambient records from the late ‘70s.) Often it’s Grouper, Liz Harris’ one-woman project.

In a few recent interviews, Barwick has brought up an analogy made by a writer some years ago: she as the white witch of this kind of music, Harris as the dark witch. Those terms kind of work, especially for Will, which may be Barwick’s most conventionally light, soothing record, and is sometimes a little inert as a result. (I get fuller contemplation out of The Magic Place and Nepenthe, although comparing them feels like comparing the sensation of swimming underwater in different lakes. And the presence of See, Know, the final song on Will, changes the record’s sum effect: It uses live drums and a faster cycle of synthesizer notes, building a crescendo, verging on a dance track.)

In general, Harris’ work is full of irresolution. It connotes loss and even erasure. By comparison, Barwick’s is consonant and genial. It connotes fulfillment and presence. Whom you prefer comes down to which disposition you want to spend your time with.

— BEN RATLIFF, NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

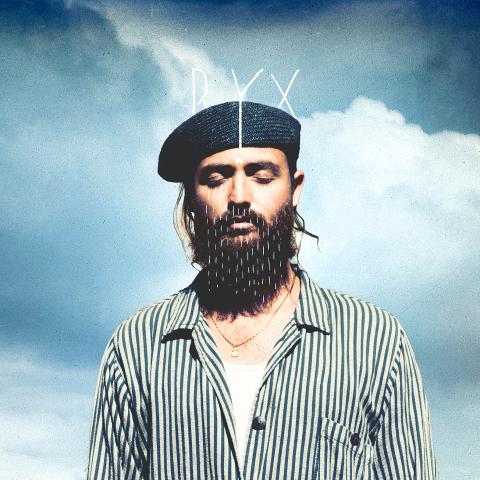

Dawn, RY X, Loma Vista

Dawn, the new album by Australian songwriter and producer RY X (born Ry Cuming), floats in a gorgeous, dolorous haze. His voice is a pearly, androgynous tenor, a vessel for liquid melancholy that blurs words.

He stretches pop structures with repetition that grows devotional, obsessive, hypnotic. When he sings about love and desire, he places himself at a confluence of the intimate and the sacred. On Salt, he sings:

We let love be like water to wine We let love be the higher design We let love be a call in the night We let love be the fire divine.

His music often suggests two other mantric, ethereal songwriters — Jeff Buckley and James Blake — and in a way, RY X has created a bridge between two awkwardly named but emotionally charged genres, psych-folk and future-R&B. An acoustic guitar or slow-moving keyboard chords are usually at the center of his productions. In some places they are all there is, but then echoes open up boundless spaces around him, other instruments waft in and his voice multiplies itself. Dance beats sometimes arrive with a subdued four-on-the-floor thump, as in Deliverance, but not always; RY X likes waltzes, too, including Only, which starts out folky and turns choirlike and reverential.

Like many other 21st-century ballad singers, RY X has dance-music connections. Between the release in 2013 of his first EP as RY X, Berlin, and his new album, he made albums with two electronic-oriented projects, the Acid and Howling. (As Ry Cuming, he also made a self-titled 2010 album of pop-rock songs that only held glimmers of his current style.)

But all the other recordings were just groundwork. Dawn brings a craftsman’s subliminal assurance to songs that seem to materialize entirely on their own terms, with an organic ebb and flow. Beacon starts out as a small string ensemble and then an acoustic, fingerpicked, undulating waltz — I fall into your mind’s eye, RY X sings — but by the end it is awash in electric-guitar feedback and his incantatory voice, singing wordless ahs. He’s both supplicant and shaper.

— JON PARELES, NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

In Movement, Jack DeJohnette, Ravi Coltrane and Matthew Garrison, ECM

Return, Jack DeJohnette, Newvelle

There’s a sly urgency in Jack DeJohnette’s backbeat, which combines a strong forward pull with something cagey and equivocal. That rhythmic signature is crucial to the feel of some Miles Davis albums from the early 1970s and a range of other music since. The latest example is In Movement, the debut ECM release by an exploratory trio with DeJohnette on drums and piano, Ravi Coltrane on saxophones and Matthew Garrison on electronics and bass guitar.

DeJohnette, 73, has known the other members of this group since they were children, by way of their fathers, saxophonist John Coltrane and bassist Jimmy Garrison (who played in Coltrane’s quartet). That lineage provides a strong background hum for the trio, informing its repertory even without the obligations of a formal tribute.

The album opens with Alabama, John Coltrane’s mournful hymn, and later hits peak intensity with Rashied, a tribute to his last drummer, Rashied Ali. (A roiling, spontaneous duo for drums and sopranino saxophone, that track feels revelatory and ablaze.) There are slow, pensive offerings like Blue in Green, from a Miles Davis album on which John Coltrane appeared.

But the story here more often involves an elliptically assertive groove. On the title track, a group improvisation, Garrison lays a framework of looped chords and effects, over which Ravi Coltrane ventures a soprano saxophone melody, elucidating a song form in real time. It’s an impressive show of collective intuition and no less transfixing than the trio’s intently hazy take on Serpentine Fire, the Earth, Wind & Fire staple, or a sinewy original titled Lydia.

A much more delicate version of Lydia, which is the name of DeJohnette’s wife, appears on his first solo piano album, Return. Just out on Newvelle — a vinyl-only subscription label whose aesthetic, in terms of visual as well as sonic design, suggests a debt to ECM — it’s an album of careful contemplation and obvious personal stake.

The piano goes even farther back than the drums for DeJohnette, whose style on Return is austere but sonorous, with viscosity in his touch and use of pedal sustain. Beyond Milton Nascimento’s Ponte De Areia, delivered as a twinkling lullaby, every track is an original, with some shades of influence: Ode to Satie broadcasts its allusions, while Silver Hollow has a stately melancholy that evokes Keith Jarrett, a longtime associate.

But when DeJohnette digs into a groove, as on The Dervish Trance or Exotic Isles, he finds a meditative space of his own. At no point does he sound like a drummer merely dabbling in melody and harmony — and yet his command of rhythm is as profound and inexplicable in this format as in any other.

— JON PARELES, NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she