Taiwan in Time: Feb. 1 to Feb. 7

Several decades after the death of painter Chen Cheng-po (陳澄波), his wife Chang Chieh (張捷) showed her daughter-in-law a wooden box she had kept hidden for many years.

In it were Chen’s undergarments, wrapped in paper and preserved with mothballs. There were two bullet holes on the undershirt. The daughter-in-law recalls in the book 228 at Chiayi Station (嘉義驛前二二八) that Chang told her to take good care of the clothes, along with a photo of Chen’s corpse with the bullet holes clearly visible.

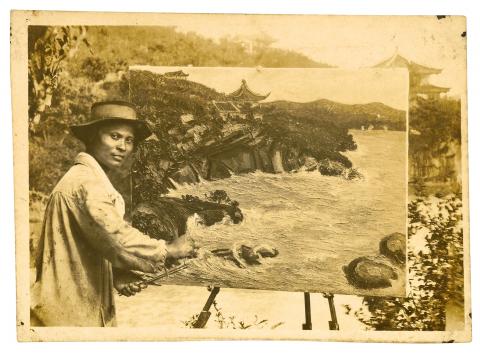

Photo: Tsai Shu-yuan, Taipei Times

“It’s proof,” Chang says. Proof that Chen was killed by government troops in 1947 during an anti-government uprising following the 228 Incident.

Chang reportedly risked her life to collect Chen’s corpse and hired a photographer to take a photo of the body, an image that is now on display at the Chiayi Municipal Museum (嘉義市立博物館).

Chen is one of those figures whose accomplishments were largely erased by politics, and his name, or at least his fate, largely disappeared from public conscious until after the lifting of martial law in 1987.

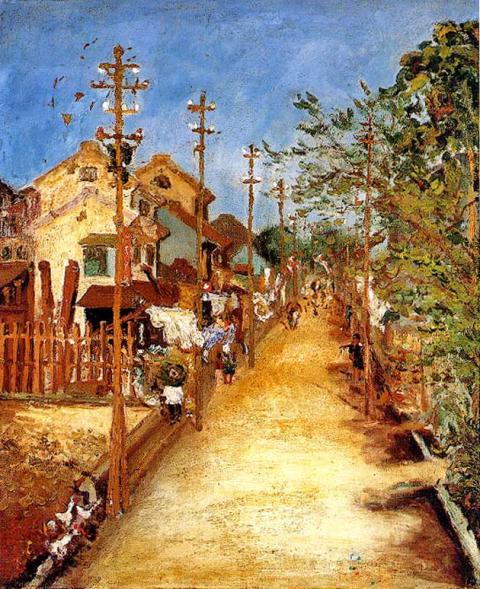

Courtesy of the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts

Even the National Central Library, which has in its collection all kinds of old books that would have been considered controversial in the past, has only one item — a collection of his paintings — about Chen dating before 1987.

In the 1997 government-published children’s book, Taiwanese Artist: Chen Cheng-po (台灣美術家: 陳澄波), release two years after former president Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) publicly apologized to 228 victims, author Chen Chang-hua (陳長華) was able to openly mention how the artist died, though she concludes it in one sentence: “In 1947, the 228 Incident happened in Taiwan, and Chen Cheng-po, who was a city councilman, became one of the incident’s unfortunate victims.”

However, in the epilogue, Chen writes, “Chen’s artistic accomplishments were unable to be made public for a long time because of the political shadow of 228. In fact, in this open era, we should revisit Chen’s journey as an artist … to pay him further respect.”

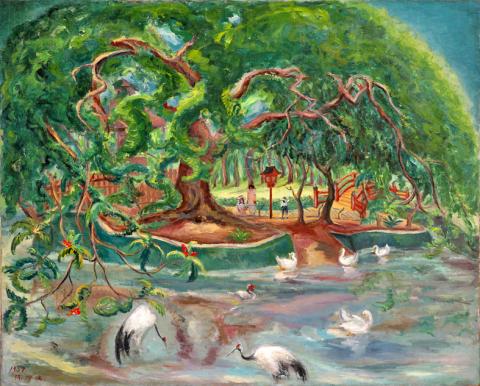

Courtesy of the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts

Chen Chang-hua may be right; ever since the public became able to openly discuss Chen Cheng-po, his fate has dominated the discourse. Aside from being a 228 victim and talented artist, what do we really know about Chen?

Born on Feb. 2, 1895 in today’s Chiayi, Chen’s family wasn’t wealthy enough for him to realize his artistic aspirations, and after attending university in Taipei he returned home and taught in public schools in the area for about seven years.

By the time he was accepted to the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (now Tokyo University of the Arts), Chen was nearly 30 years old. In just two years, his oil painting of a street scene in Chiayi was accepted to the annual prestigious Japan Imperial Art Exhibition, and another street scene also made the show the following year. This made Chen the first Taiwanese to have a Western-style painting featured in the exhibition.

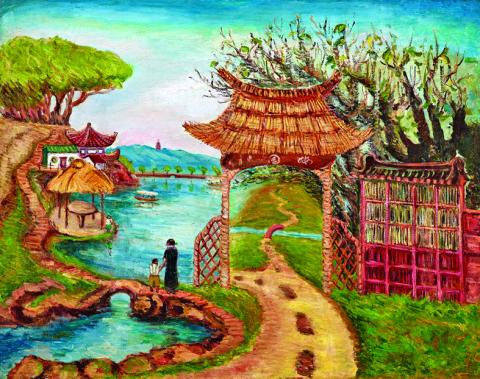

Courtesy of Liang Gallery

Chen graduated in 1929 with a degree in Western art and headed to Shanghai, where he spent four years as an art teacher. While in China, he learned traditional Chinese painting techniques, which he integrated into his techniques.

Japan invaded Shanghai in 1932, and as Japanese citizens, Taiwanese living in China also became the target of anti-Japanese sentiment. Chen returned to Chiayi in 1933 and became a full-time artist. Life wasn’t easy, as he reportedly couldn’t afford his daughter’s dowry and provided two paintings instead.

He’s reported to have said, “As someone whose mission it is to create art, if I can’t live for art and die for art, how can I call myself an artist?”

Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Japanese surrendered in 1945. Since Chen learned Mandarin in Shanghai, he took up the position as vice-head of Chiayi’s Preparatory Committee to Welcome the National Government (歡迎國民政府籌備委員會).

This foray into politics would eventually seal his fate. The next year, he joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and served in the first Chiayi city council.

Historian Wang Chao-wen (王昭文) writes that when the 228 incident broke out, some of the fiercest fighting between civilians and government troops took place in Chiayi. On March 11, 1947, after a nine-day standoff between the military in the airport and armed civilians, Chen and several other representatives entered the airport in an attempt to negotiate with the government.

The military instead arrested four of the representatives, including Chen, and publicly shot them in front of Chiayi’s train station without a trial on March 25. Chen’s lifeless body lay on the streets of Chiayi, surrounded by scenes that he loved to paint so much, for three days until his wife finally ventured out and collected the corpse.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a